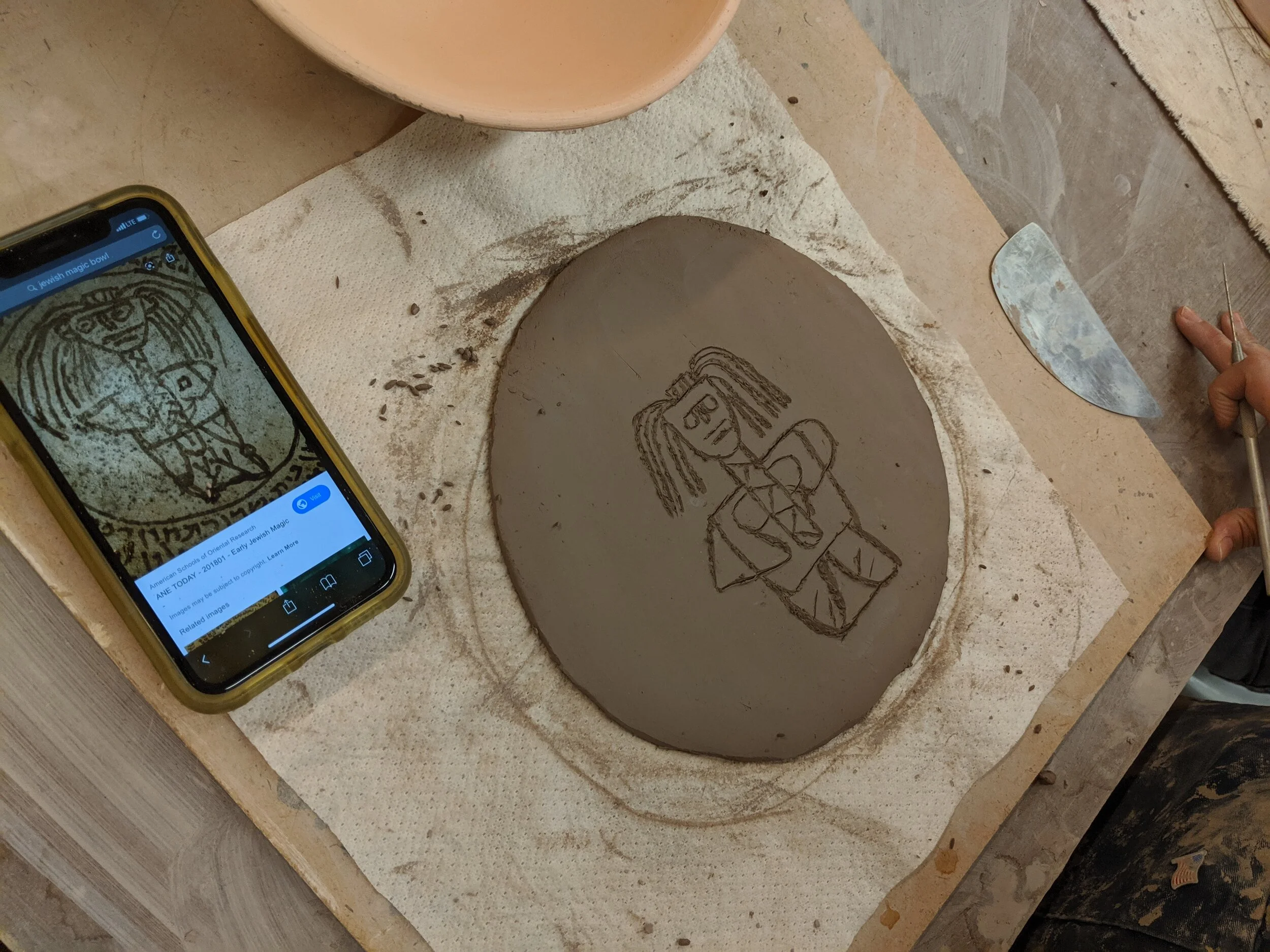

“It was important to me that my students see incantation bowls as more than symbols, or even just textual incantations, but as a real form of knowledge embodied in relationships between human subjects, divine beings, and material objects.”

Read MoreAncient Muses and Student Poets: Storytelling in Verse

Late antique poets – with their penchant for storytelling and dramatization – offered students plenty of examples to emulate.

Read MoreThinking Materially: Making Ostraca in the Classroom

“I took this as an opportunity to think with my students about writing as a physical enterprise and text as material artifact. To accomplish this, I decided I would have my students make their own ostraca (sg. ostracon), or small sherds of inscribed pottery, in class."

Read MorePedagogy | Teaching Archive Trouble

Where do we get the texts that we have? Is the archive a neutral record of the past? How does the archive serve a quest for knowledge of the past? How does it interact with time, identity, and the social world?

Read MoreMateriality of Death and Afterlife: Visit to Local Cemetery

Teaching a course on a topic like “Death and Afterlife” offers a unique opportunity to engage with students. While in other courses students may feel intimidated for lacking content expertise, typically everyone has some experience with death and mourning.

Read MoreMoodle Midrash

By asking the students to reflect critically on their own interpretations, they gained a much sharper awareness of the perspectives of their own questions: what are the different stakes that are present in the text, for different readers? What did it mean to read is a “scholar,” and what did it mean to read as a “believer?” What were the locations where those stakes overlapped, and what did that tell us about the enterprise’s entire construction?

Read MoreThe Meme Bible

James Walters shares his assignment for “memeing” the Bible.

Read MoreDissertation Spotlight | Christianizing Knowledge

There are several ways to think about the rise of Christianity. I have chosen to tell this story in this manner because I think that it helps to elucidate a number of fascinating shifts in late antiquity, and some of the shifts that I detail continue to reverberate today.

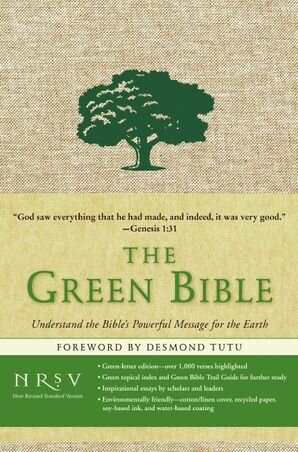

Read MoreTrees and Text: A Material Ecocritical Exploration of Gen. 2:4b–3:24 in The Green Bible

While these two analytical approaches are ostensibly discrete they represent two modes of inquiry that are unique to material ecocritical discourse: ‘matter in text’ and ‘matter as text’, respectively. This approach places trees at the center of my study; narrated trees are the focus of my textual analysis of Gen. 2:4b–3:24 and real-world trees are the primary natural material from which the text of the Green Bible is manufactured.

Read MoreUsing the Digital Syriac Corpus for Online Syriac Instruction

Have you found your Syriac course suddenly converted to an online course? If so, the Digital Syriac Corpus is here to help!

Read MoreRewriting and (Re)negotiating Gender: A Study of the Depictions of the Matriarchs in the Book of Jubilees

Hans Schilling, “Judith Beheading Holofernes” (detail) in Barlaam and Josaphat, 1469. J. Paul Getty Museum.

Hans Schilling, “Judith Beheading Holofernes” (detail) in Barlaam and Josaphat, 1469. J. Paul Getty Museum.

My dissertation seeks to identify the motives and priorities that guided the author of Jubilees in his rewriting of the biblical stories concerning the matriarchs and asks if Jubilees was unique in its foregrounding of female characters or dealt with them in a manner that was typical of the then literary Zeitgeist.

Read MoreThe Rabbinic Legal Imagination

Talmud Bavli | Bavarian State Library, Munich, Germany, 1342; Ms. 95, page 1152.

Talmud Bavli | Bavarian State Library, Munich, Germany, 1342; Ms. 95, page 1152.

My dissertation offers a new lens into rabbinic legal activity by using close literary analysis of legal passages to show how late rabbinic thought uniquely partakes of broader Sassanian scholastic cultural trends.

Read MorePandemic Pedagogy: Pamphlet Final Projects and Laughter

If nothing else, let it be known that a strong pun game helps in all circumstances.

If nothing else, let it be known that a strong pun game helps in all circumstances.

Teaching during global pandemic means improvisation. This short article shares my experience of an improvised assignment that worked, how it worked, and what good came out of it: museum-style pamphlets. Take it if you like, adapt it as you will, and let me know what works better when you do.

The Backstory

The origin story of these pamphlets begins with a simple observation: poster sessions are cool. At the small liberal art college at which I taught this year, disciplines with a lot of majors – Economics, Biochemistry, Business Administration, and so on – pack the library at the end of each semester with glossy student posters and enthusiastic presentations. There is a bit of buzz and excitement, and it releases students and faculty alike from the cycle of paper research and editing.

So, I decided that for my seminar course this term – “The Rise of Religion and the Fall of Rome”; put the fall of Rome in your title, and they will come – I would move away from the final paper model and take the course into display space. Two reasons: first, I avoid compulsory formal research papers for undergraduates. They can be exceptional, even life-shaping, experiences for the right people, especially those of us temperamentally invested in long-form research writing, but they are also very time-consuming. In American academic existence, students and instructors – especially contingent and non-tenure track instructors – have so many competing demands on their time. For a lot of students, an extended research task is a gift. For a lot of students – and, for the instructor – it can become a chore. Second, visibility. The Religion department at Washington and Lee has very few majors, and it struggles to fill even the classes of established faculty. I figured raising the profile of the department, as visiting faculty, was a mitzvah.

Of course, neat as poster sessions might be, they become more difficult if adverse circumstances intervene. Like many teachers, the spread of SARS-CoV-2 and resultant state of pandemic meant I reinvented courses on the fly, including their final assignments. The library was closed, students were scattered to the winds, and as a small teaching-intensive college – even one with a disproportionately large endowment – the online resources available for research were limited.

In my survey courses, an alternative was simpler: a portfolio based final with miniature writing assignments. Students still get to develop writing expertise, while everyone saves the time it takes to write, read, and edit more extended research pieces. It takes just as much skill to write with concision. In my seminar course, however, I wanted three things.First, I wanted students to come away with the ability to communicate knowledge about their material with a degree of critical selectivity. Second, I wanted an assignment that combined knowledge management with visual display. Third, I wanted the final to be less work for everyone. Suddenly, faculty were juggling converted online-only courses and students were dealing all at once with the fallout from several faculty juggling converted online-only courses. So, what assignment ticked all the boxes?

My students pointed to a solution when they began to push for sources beyond the hyper-elite material that dominated much of the first half of our course. Our week on Ḥimyar and Aksum proved the crunch point. Students found the privileged position of much of the literary and epigraphic evidence, as well as the political and economic historical focus of modern scholarship, a tad frustrating. Say, for example, that we know from his Mārib inscription that the sixth-century Aksumite king Kālēb justified his pious militancy partly through repurposed psalms. Sure – but what did your average Ḥimyarite on the street think of Kālēb’s invasion? To respond to this student desire, I wanted to find a way to make this social-historical, even micro-historical, approach play into the final.

A possibility sprang to mind: what if students designed pamphlets? Visually appealing, they package up concise information, and are easy to read and share. The only one of my three assignment stipulations in question was the third: would they be less work? Pamphlets take more time than you might think – effective design was a second-order issue, but as anyone who has even ever “whipped up a poster quickly” for an event will tell you, even basic design is a skill. But it is a different type of labour: students were writing a lot, in the form of discussions forums and final papers, so visual design is good time spent. In a sense, to return to the beginning of the story, they are portable posters. Plus, pamphlets are one of my favourite things about museums, especially when they come with little maps, and even when (speaking purely hypothetically) they get deposited in a kitchen drawer only to be excavated when we need that drawer for cat food.

The Assignment

Having said a little about how the assignment came together (in effect, it improvised itself into existence), I want to spend a little time giving a short how-to, and then some practical critique on what needs future tweaks. I had the opportunity to discuss with students extensively, so a lot of this was possible because of close communication with a dedicated group. It was important to answer student questions early. I also provided a short rubric. The main things to note: first, I provided a concrete example of the format (thank you: internet). Second, I stipulated that this was “research-lite.” Third, I made sure to give them a list of starter resources. Students did use images from various sites, as well as going out and finding their own. Stars of the show included museum collections, especially Penn’s collection of Aramaic incantation bowls.

Students, as you can see from the examples, rose to the occasion. The assignment proved flexible. The students split half-and-half into folks keen to examine a particular type of object – amulets, magic bowls, graffiti, and so on – and those interested in telling a specific story – about the legacy of Paul, the legend of Frumentius in Ethiopia, and so on. Most students subdivided a Word document into three columns per landscape page; at least one student made use of the trial version of Canva, a handy design tool with lots of templates and (at time of writing) a flexible free plan.

There is no escape from Zoom.

The Debrief

No first attempt is perfect, and there are a couple of things I noticed for tweaking in future. First, I would stipulate more explicitly that students think about a pamphlet that might belong in a museum space. In general, students who engaged specific objects more easily adapted to the format. A couple of students chose topics better suited to research papers and ended up with something more like a paper compressed into six panels. Second, if planning to move towards a pamphlet assignment, I think I’ll encourage students themselves to find real-world examples of the sort of thing we’re talking about. Finally, I made very few tech suggestions: the student design was at their initiative, mostly to make this low-stakes in the current high-stress, high-pressure situation. I do think, in retrospect, more direction in terms of recommended method might have helped those who struggled a little with the format to engage with more confidence.

You heard it here first: resurrecting fish just doesn’t make the headlines like it did back in the way.

Perhaps the most valuable thing to come out of all of this was an opportunity to share a collective sense of humour. The shift towards a more visual presentation format seems to have helped students relax a little. This is also an issue with academic writing more broadly. With a few noble exceptions, academic literature is often not very funny. Student papers even less so. For some reason, especially odd given the hilarity threaded through much of our late antique material, we tend not to laugh at our sources – or ourselves – nearly often enough in writing. When scholars get together, the ability to crack a joke at John Chrysostom’s expense or to quip about the oven of Akhnai marks you as a good egg. In the classroom, nobody regrets a giggle at the apostle Peter’s resurrection of a smoked fish. So, why deprive us of that in writing?

In any case, the lack of levity common in academic writing was nowhere to be found with these pamphlets. Perhaps the form shifted the assignment into a genre less alienated from the ability to crack a joke. Maybe the emphasis on display meant students paid more attention to the rhetoric and style of presentation – a lesson for reading ancient sources if there ever was one. Possibly, the fact the assignment was fun meant it offered a little relief from their other final assignments. In any case, the payoff of the assignment for me was a light-hearted grading session. There might be no stronger a recommendation for a pedagogical choice than this: if it makes you and your students laugh even as you understand something better together, especially right now, it might well be worth doing.

I endorse no museum that lacks adorable demonic stuffed animals.

Matthew Chalmers is currently Visiting Assistant Professor of Religion at Washington and Lee University and Deputy Editor of Late Antiquity at Ancient Jew Review (Twitter: @Matt_J_Chalmers).

Notes on the Historical Paul and his Intellectual Activity

This essay thus explores Paul as a mediating intellectual who uses the space in his letters to imagine a new social form, and likewise to establish it in the minds of his audience in a persuasive way.

Read MoreAsynchronous Online Teaching: How Do You Visit a Museum from Home?

Roundel with Entry into Jerusalem, 10th century, German, on view at The Met Cloisters, Gallery 10

Roundel with Entry into Jerusalem, 10th century, German, on view at The Met Cloisters, Gallery 10

Instead of a physical pilgrimage up the hill of Fort Tryon Park in Washington Heights to the Cloisters, or down Fifth Avenue to the Met’s main collection, I decided that we would tour the (web)sites of some of the world’s best art collections.

Read MorePandemic Pedagogy: Annotation as Close Reading

One of my central pedagogical goals is to cultivate thoughtful discussion about primary sources. I model nuanced and creative practices of close reading from the front of the classroom, but this is a skill that students develop only by doing. As a result, I regularly devote classroom time to guided exercises that interpret artifacts (coins, monuments, mosaics, etc.) and translated primary texts. I encourage students to ask questions of the sources, to make observations, to disagree respectfully with one another, and to investigate the implications of their interpretations. This rewarding back-and-forth process can feel hard to replicate in other media.

As many teachers move their pedagogy into online media over the coming weeks, in this article I introduce a set of tools and practices that facilitate shared conversation through collaborative digital annotation of primary texts. This approach is not the same as a guided close reading in class, but it pursues the same objectives and even affords some benefits that aren’t realized in face-to-face classroom discussions.

The Basics

Over the remainder of the spring semester, my students will be using a tool named Hypothesis for this collaborative practice of annotation. One can accomplish similar goals in a shared Google Document or with tools like Perusall or NowComment. More complex online tools like Digital Mappa, Omeka, or Mirador can also facilitate annotation of texts or artifacts. (A number of these tools can be integrated into institutional learning management systems, too.)

This semester, I have divided my students into groups of approximately six annotators. Each group uses Hypothesis to annotate a short primary text every week. Each group annotates the same text. In my experience, the ideal length for texts is one to three pages. To preserve the conversational back-and-forth of the classroom environment, I ask each student to add at least two annotations and to respond to at least two comments from others. I grade this low-stakes assignment based on completion. If a student engages the text and their peers, then they get full credit.

I assign annotations in the period leading up to the lecture in which I discuss the annotated primary text. In my lecture, I address areas of confusion and incorporate excellent student insights (acknowledging the student’s work, of course). It is also possible to use annotation assignments as follow-on tasks to consolidate knowledge and prompt further exploration after a text has been introduced in a lecture segment. I provide student feedback by responding directly in each annotation cluster.

Productive Conversations

The central challenge of this annotation assignment is to both facilitate shared conversation that contributes to the overarching goals of the class and also encourage students’ creative inquiry. Instructors assign particular texts for specific reasons. Certain narratives, certain problems, certain lacunae are why we have chosen this text for our class. Here, as in a guided classroom discussion, the goal is to cultivate good habits of textual analysis without getting bogged down with excessive focus on details that do not advance the overall pedagogical aims of the course. In classroom discussion, an instructor can intervene in real time in order to keep things on track. Asynchronous annotation assignments require a bit more planning.

The most effective way to accomplish this goal will vary based on the level of the course, the stage in the course, and the instructor’s specific goals for a particular close reading.

For most texts, I pre-annotate with background details. I might note the date of the text, provide information about the author, and give brief clarifications about unusual vocabulary or cultural practices. This mirrors my classroom practice, where I supply background information and draw attention specific details in the text.

To prompt thoughtful annotation, I frequently pose specific questions. Sometimes I instruct students to read the text in light of another text we have already discussed. (For example, in one assignment I asked students to compare Paul’s rhetoric about gift-giving in 2 Corinthians 8 with our previous reading of Seneca’s On Benefits.) In other cases, I ask them to focus on particular kinds of details. (For example, what does Pliny’s Epistle 96 indicate about the social statuses of Christ-followers in early second-century Roman Bithynia?) My goal is not to short-circuit textual inquiry, but to keep students’ questions pointed in productive directions.

With more advanced students, and often later in the semester, I leave annotation assignments more open-ended and simply invite students to observe details of the text that connect to conversations we’re already having. This practice assumes that students have already developed habits of attention to textual detail and works best, in my experience, when the course has a strong through-line to provide context for ongoing discussions.

Even with relatively directed assignments, however, I encourage students to note striking details and to flag questions or points of confusion. I’m regularly delighted to discover that students have identified details and connections that I had previously overlooked.

Building Intellectual Community

One of the strengths of collaborative assignments is that students can see themselves as contributors to a shared intellectual community, rather than just consumers of delivered digital content. In introducing this annotation assignment, I encourage my students to see themselves as participating in one of the oldest modes of scholarship, with similar practices of commentary going back to the ancient Mediterranean. Annotation is a way to involve students in the creation of knowledge.

Annotation assignments contribute to a classroom dynamic of inclusive dialogue. As a low-stakes mode of collaborative scholarship, annotation encourages all students to contribute their thoughts. Annotations in previous courses have elicited brilliant insights from students who were reluctant to share their thoughts aloud in the classroom. When students disagree—as I encourage them to do—their disagreements stay focused on the textual evidence. Moreover, because annotation assignments invite students to interact with specific details of a relatively short primary text, students who might otherwise feel overwhelmed frequently find it easier to make concrete contributions.

As is particularly relevant in this time of digital distance, annotation assignments build a sense of intellectual community. I have found that my students appreciate the opportunity to respond directly to one another. Their collaborative annotations concretize the fact that they are not alone as they finish the semester. They can see that classmates are reading the same texts and asking similar questions. Perhaps in part because of this sense of community, my students’ comments on each other’s annotations this semester have been astonishingly rich. This semester, I have increasingly come to see a shared sense of intellectual community as the primary benefit of this pedagogical practice.

Strengths and Weaknesses

Before assigning digital annotations, it is helpful to think through strengths and weaknesses of this pedagogical approach. As I have suggested in this essay, the strengths are manifold.

· Annotation is a mode of collaborative scholarship which encourages all students to participate.

· Annotation assignments are asynchronous. Students can work at their own pace and do not require a high-speed internet connection. Especially in a period of pandemic disruption, this levels the playing field for students.

· Annotation assignments are not limited to texts. They can be used for maps, coins, and other sources.

· Many annotation tools are free and low-maintenance. Hypothesis can be integrated into learning management systems like Blackboard, Canvas, Moodle, and Sakai. (It took me about fifteen minutes to do.) Many other tools are similarly user-friendly for both instructors and students.

As with any approach, digital annotation assignments have weaknesses.

· Annotated documents can become confusing and cluttered if a large number of students are annotating a relatively short text. For this reason, annotation assignments work best if students are divided into groups with six to eight annotators each. The groups can each annotate the same text or different texts can be assigned to different groups of annotators.

· While annotation has fewer technological requirements than synchronous approaches like Zoom lectures, it can still exclude students who lack reliable internet access or who can only access the internet with mobile phones. Consider students’ access to the internet before selecting this assignment model. If some members of the class have limited or unreliable internet access, avoid requiring rapid turn-around times for annotations and responses.

A Final Thought

Collaborative annotation assignments and technologies are fruitful beyond the pandemic context. I’ve used similar annotation assignments in classes that involved face-to-face classroom sessions multiple times each week. Pandemic pedagogy poses many new challenges with far too little time, but I hope that the skills we must all-too-quickly develop will continue to be fruitful in varied course formats going forward.

Jeremiah Coogan holds a PhD in Christianity and Judaism in Antiquity from the University of Notre Dame. In autumn 2020 he will begin a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Postdoctoral Fellowship at the University of Oxford.

Dissertation Spotlight | Stories, Saints, and Sanctity between Christianity and Islam in the Middle Ages

Christian hagiography was a powerful medium with which Muslim communities built and expressed their distinct local identities, religious notions, and collective memories. In order to understand this medium, this dissertation undertakes an intricate study of the mechanisms of hagiographical transmission between Christianity and Islam.

Read MoreAAR/SBL 2019 Review Panel | Moment of Reckoning

AJR is happy to host the the review panel on Dr. Ellen Muehlberger’s recent publication, Moment of Reckoning: Imagined Death and Its Consequences in Late Ancient Christianity.

Read MoreAAR/SBL 2019 Review Panel | More Reckoning: A Response

The primary portable argument of my book is that the specific things we anticipate in the future, for ourselves and for others, shape the way we act, for ourselves and for others.

Read MoreAAR/SBL 2019 Review Panel | Speaking of Death: Rhetoric and the Postmortal

Moment of Reckoning is full of bold and compelling arguments. But to my mind the most intriguing, if subtle, concerns the relationship between rhetoric and identity. How do words define people? How might personhood be conjured, and changed, by language?

Read More

![Nikos Engonopoulos, Poet and Muse (1938) [Wikimedia].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5449167fe4b078c86b41f810/1597960393283-09LT3VT2ANQA9M5BXHYV/1024px-Poet_and_Muse.jpg)

![Panel from an ivory dyptich of Rufius Probianus, who was vicarius urbis Romae around 400 CE. [Berlin, Staatsbibliothek Ms. theol. lat. fol. 323, Buchkasten].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5449167fe4b078c86b41f810/1592842801661-0Y732O4NHSY6BA17T4WU/Unknown.jpeg)

![Roman road in Hippos [Image courtesy of the author].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5449167fe4b078c86b41f810/1589476300762-L2Q4ARU6LNAWDM9ME19W/GetAttachmentThumbnail.jpg)

![Gustav Klimt, Death and Life (ca. 1910-1915) Leopold Museum [Wikimedia].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5449167fe4b078c86b41f810/1586099901770-4NFRYO6802LVINJERIG0/1024px-Gustav_Klimt_-_Death_and_Life_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

![Hieronymus Bosch, Death and the Miser (ca. 1494), National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC [Wikimedia]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5449167fe4b078c86b41f810/1585763534255-EG2GMP4KQ9LDEZ7JRUUQ/800px-Hieronymus_Bosch_-_Death_and_the_Miser_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)