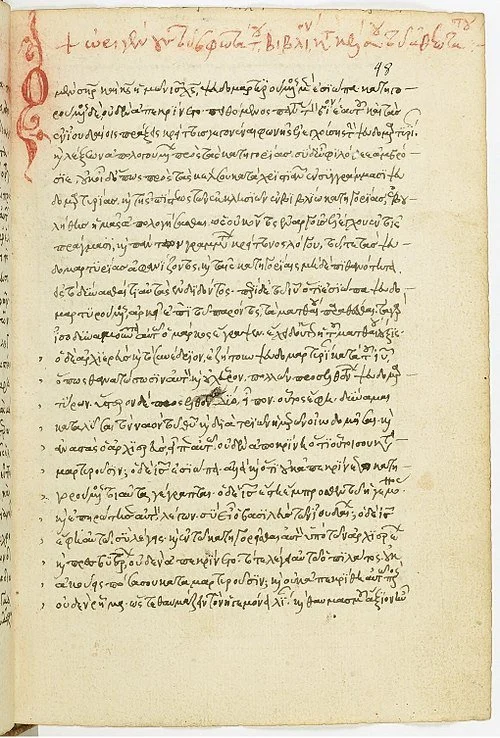

A forum in celebration of Robin Darling Young and Joseph Wilson Trigg’s The Contra Celsum of Origen: English Translation and Facing Greek text (Washington and Cambridge: Harvard University Press/Dumbarton Oaks, 2026).

Another apt turn of phrase for Boarding School Life is: “it is not a difficult job, but it is a demanding one.” But the benefits, in my mind, far outweigh the costs. If you really enjoy teaching, coaching, and mentoring excited and curious young people, this might be an avenue you should seriously consider.

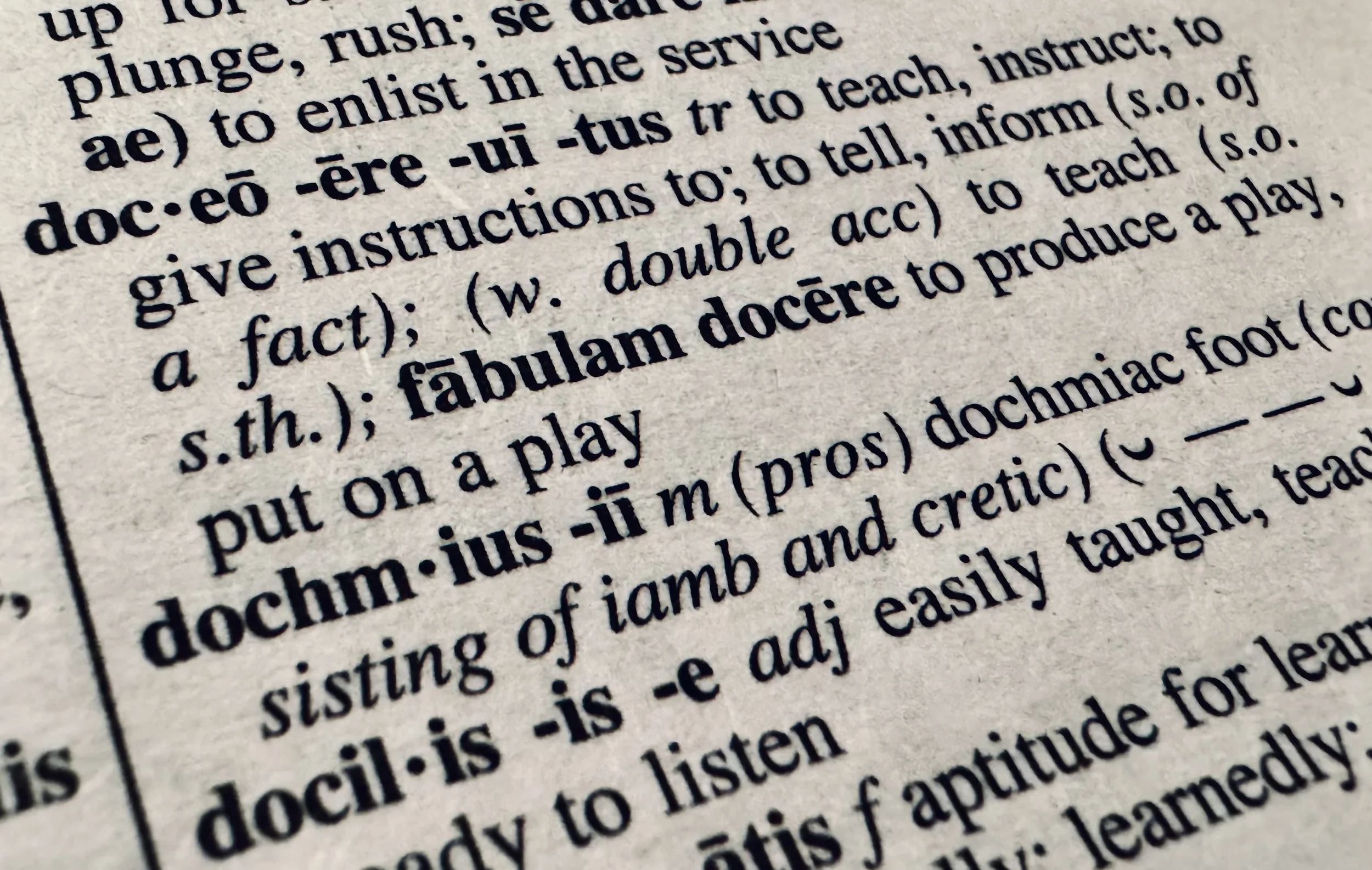

Secondary-turned academics are indispensable not merely for their banausic training and credentials. At their best, scholars of the humanities embody love of learning and wisdom over mere appearance and sophistry. Where institutions of learning tilt toward test-prep and job training, PhD-trained teachers must fight to keep alive a humanistic appreciation of learning for its own sake.

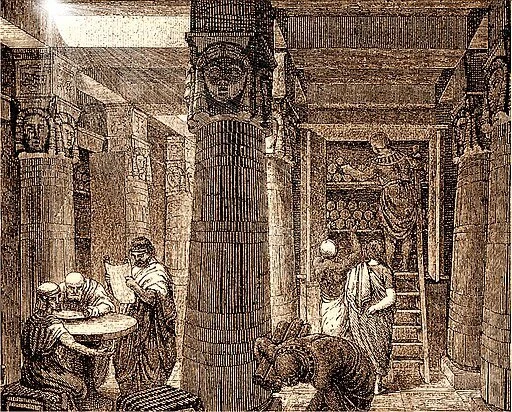

In Contra Celsum, Origen deepens this association between incorporeal intermediaries and what we typically classify as constituting the political.

Origen too imitated Socrates’s example, not least in his approach to rational inquiry. Origen frequently speaks of Socrates as a model philosopher, though he is not above criticism.

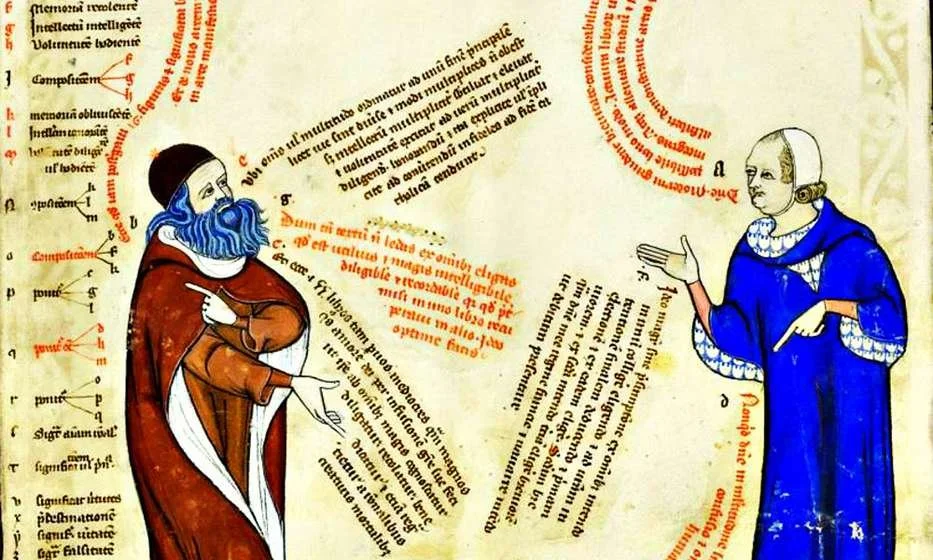

Joseph Trigg and Robin Darling Young posit the unabashedly philosophical character of Celsus’s challenge and Origen’s response as the basis of their project.

In this short tribute to Origen and his translators, I suggest that, among much else, Origen shows paradoxically how strong a mainstream polytheist’s case could be against Christianity in the second century, and how even a brilliant apologist could struggle to meet it.

A forum in celebration of Robin Darling Young and Joseph Wilson Trigg’s The Contra Celsum of Origen: English Translation and Facing Greek text (Washington and Cambridge: Harvard University Press/Dumbarton Oaks, 2026).

Celsus’ views about empire and cult, whether they were pagan or Christian, were far from dead in the fourth century; they appear in Christian sermons and treatises – not just in their pagan echoes in Porphyry and Julian.

A Memory of Violence offers a useful overview for anyone interested in understanding Chalcedon and its effects at a more detailed level, as well as those interested in the history of Christianity writ large.

Scully’s book commendably demonstrates the need for renewed and careful attention to a pattern of thought that has been treated poorly, and it does so with sharp analytical clarity.

“Ophir insists that he is not simply claiming the modern sovereign as a “secularized political concept,” but something deeper: a deification of the state itself, as the one concept that we cannot think without, just as the biblical writers could not imagine not being ruled by God.”