This article introduces a classroom activity called a Text Lab, which helps students engage critically with ancient texts while familiarizing them with the tools and scholarship necessary to analyze these sources.

In this article, we argue that, despite and precisely because of these real cautions, public scholarship can further three core academic responsibilities: teaching, service, and even research.

“I came to a realization similar to the one about composition history, though considerably more mundane: the jumble of words, numbers, and punctuation that make up a biblical reference is objectively confusing if you’re not used to it!”

"Although we might not have faith in these beliefs today, I have found that while teaching my Roman Empire class, having students reconstruct these fastidious rules, in order to learn to engage with the ars of divination, can provide them with deeper access into Roman beliefs about communication with the gods."

Jewish and Christian Women in the Ancient Mediterranean (Routledge, 2022) is the first ready-made classroom resource dedicated to the study of ancient Jewish and Christian women in their wider Mediterranean context.

“In this exercise, students are not simply studying and rereading material but testing themselves repeatedly. The process of making the cards and even coming up with helpful questions for their peers is a challenging task.”

Raphael Magarik describes the value of assigning biblical novels in an introduction to the Bible course.

“I want to resist the impulse to see my students as numerical marks to be ranked against each other. Instead, I encourage their individuality, unique ways of seeing the world, and habits of thought to become partners in the evaluation process.”

As historical-critical scholars, we need to realize that we cannot be absolutely sure of our conclusions, and that like any discipline, they may change over time as the result of new evidence or new hypotheses that better explain old evidence...Yet—I know how uncomfortable these methods make many students from religious backgrounds. For that reason, in the very first class I introduce an image of a Monopoly board, and explain that my class is like the game of Monopoly.

“I tell students that writing is an inherently collaborative enterprise: we write in conversation with previous scholarship; we write for a future audience; we share drafts with colleagues and mentors; we submit work for peer review and to editors and editorial boards; we anticipate reviews of our books; we hope that our work will be engaged.”

No two students created the same profile—even though many of them selected the same character—and this, too, was instructive. At its core, this assignment was about practicing interpretation.

Elena Dugan shares activities for both Hebrew Bible and New Testament classes that examines the distinction between magic and miracle.

With a “flipped classroom” format, this graduate seminar enabled students to create a commentary on key psalms with a focus on the history of Israelite religion.

“This lesson plan has been an effective means of reinforcing the physical, manuscript-based analysis of textual criticism, over against the theoretical texts of source criticism.”

If we are to individually tailor our responses, how can we figure out what sort of feedback someone is seeking?

A few years ago, I began a simple practice that has transformed my teaching. Now, I look forward to the first few minutes of class as my favorite time.

In writing their own prayers and playing with the literary and religious elements of myth and history, the students actively imagine the relevance these divine beings could have had for their worshippers in order to better integrate course content.

What can stories about Loki, Norse god and (more recently) Marvel character, teach us about biblical literature?

“The ‘UnEssay’ is a creative assignment that helps students learn long-term project management, critical and reflective thinking, analytical writing ability, and a variety of technical skills.”

The “Dead Sea Scrolls Brochure” assignment has two parts: the physical brochure and a 2-page reflective explanation of the brochure.

Many academics only write about their teaching at three key moments: composing application dossiers, writing course syllabi, and perhaps when reflecting for annual reviews or tenure submissions. But there are many venues that, with the right framing, could showcase how you translate your expertise for students and what you’ve learned from the trial-and-error repetition of activities, paper prompts, and entire courses.

What actor should play this person in a movie about their life? In my classes on ancient Judaism, I ask students this question a lot.

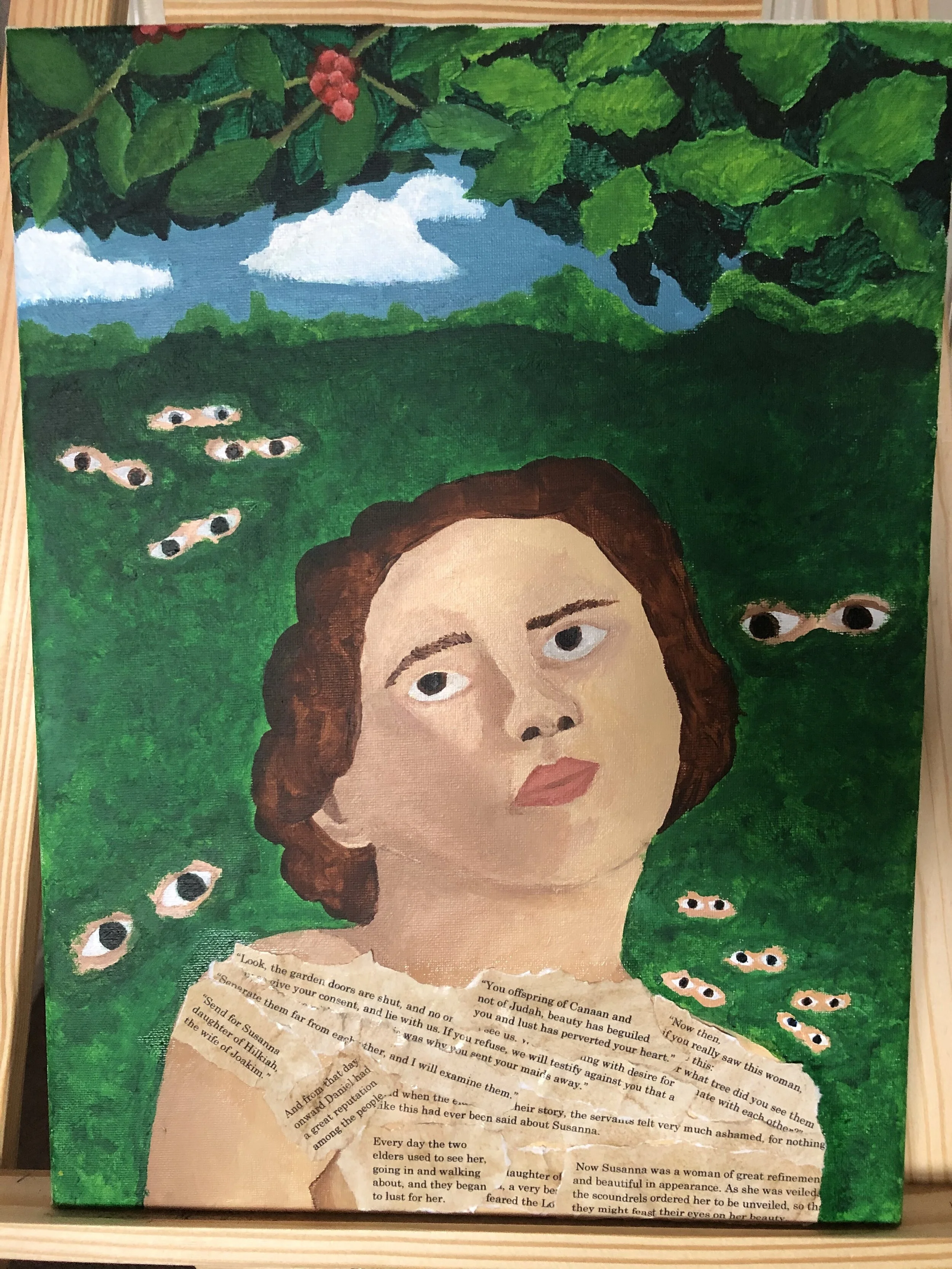

This assignment encouraged students to confront and interrogate their role (even, at times, their complicity) as active participants in forming martyrdom traditions through the act of vivifying these images with color.

Dr. Reyhan Durmaz describes how her students brought objects to life with creative autobiographies.

“To give students a feel for the materiality of ancient magic, I decided this year to walk them through the process of making a magical papyrus using materials similar to those used in antiquity.”

“Since so much of my own interest in the ancient world has been fostered by encounters with various forms of material culture, I wanted to ensure that even though my students would be taking this class virtually, they would still have tangible materials to see, touch, feel, and even smell.”

“It was important to me that my students see incantation bowls as more than symbols, or even just textual incantations, but as a real form of knowledge embodied in relationships between human subjects, divine beings, and material objects.”

Late antique poets – with their penchant for storytelling and dramatization – offered students plenty of examples to emulate.

“I took this as an opportunity to think with my students about writing as a physical enterprise and text as material artifact. To accomplish this, I decided I would have my students make their own ostraca (sg. ostracon), or small sherds of inscribed pottery, in class."