Page of Rashi’s Commentary on the Megillot, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Hebrew Bible seminars at a graduate level usually require students to read the biblical text in Hebrew and then use their translations as a springboard for discussing larger historical and conceptual issues. The format of such seminars typically falls into a familiar pattern. The students read a text of the Hebrew Bible as homework. Class time then consists of the instructor progressively moving around the classroom, asking the students to translate a given verse and then quizzing them on aspects of its vocabulary and grammar. Such an approach has obvious benefits. It puts the Hebrew text front and center of the learning experience, it motivates students to carefully prepare the text before class, and it ensures that class time is devoted to honing the students’ philological skills. But there are also pedagogical drawbacks to the common “circle translation” method, and to its more aggressive cousin, the “cold call translation” method. First, both methods can create an unfortunate dynamic whereby students who are less confident reading out loud in Hebrew feel embarrassed, while students with greater reading fluency tend to breeze through. The result is that the seminar becomes more of a test of confidence than competence. Second, the circle translation tends to foster a learning environment in which the instructor is the arbitrator of correct answers, and the students succeed only if they can supply the correct answer while under pressure. Third, such a heavy focus on translating and parsing can leave little time for students to share their ideas on more theoretical matters concerning the interpretation of the text and its place in the history of research.

In my graduate seminar “History of God: Evidence from the Psalms,” I wanted to explore alternative ways of engaging deeply with the Hebrew psalms without falling into the “circle translation” trap. Together with the Derek Bok Center at Harvard University, I created a format for the class that required, as homework, that the students each assumed one of the research roles involved in creating a commentary – an annotated translation of a text, explaining certain key features – and came to class ready to share their results with their peers. All of the roles required the students to carefully read the psalm set for that week, in Hebrew, before class. However, only one student was responsible each week for sharing their translation with the group, along with an analysis of the poetic structure of the psalm.

Page 1 of Andrew Hile’s handout presenting his translation Psalm 68

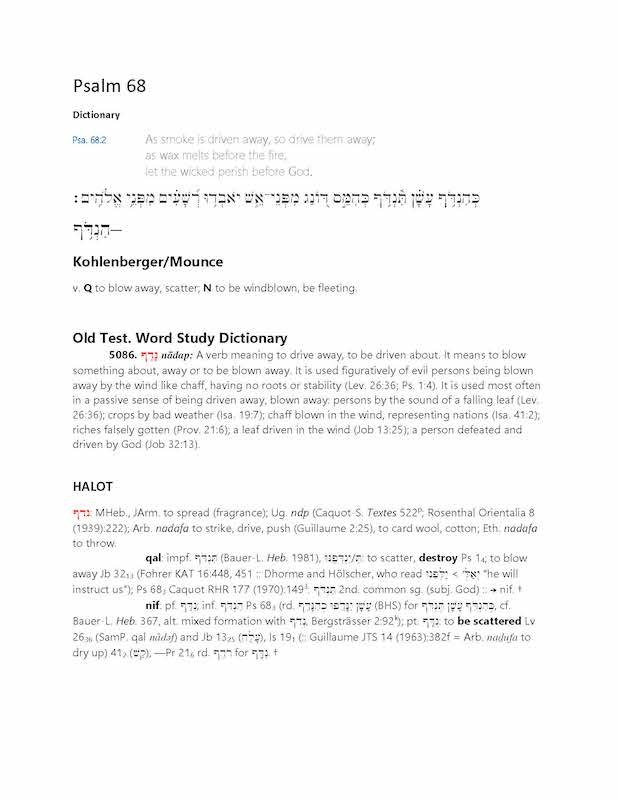

Another student was responsible for doing a deep dive in Hebrew grammars and dictionaries, and to come to class ready to offer detailed philological comments on noteworthy features of the Hebrew of the psalm, including unusual lexemes or syntactical structures.

Page 1 of Byron Russell’s handout presenting philological notes on Psalm 68

Other exegetical roles available to students could include presenting possible redactional seams within the text, discussing the opposing sides in debates concerning the dating of the psalm or its Sitz im Leben, or explaining the relationship between the psalm and other biblical passages. I tended not to assign these roles to the students, preferring instead to let them pick their role each week according to what they felt most comfortable with or what best aligned with their interests. To aid the students as they prepared for their roles, each week I uploaded scans from a handful of commentaries to the online learning management system, as well as a couple of articles or book chapters. My role, as instructor, tended to stay the same each week: I prepared a small dossier of extra-biblical evidence that might illuminate the broader historical context in which the psalm emerged, whether that be archaeological finds, epigraphic sources, or comparative evidence from other ancient Near Eastern contexts. Together, these materials served as a rich set of resources students could plumb for their commentaries as they developed.

The results of the seminar were truly excellent, sometimes astoundingly so. By the end of the semester, we had collectively analyzed the Hebrew text of eight psalms from multiple different angles, roughly covering the material one would expect to find in a critical commentary (literary criticism, source criticism, reception history, etc.). Adopting a flipped classroom format did not come at the expense of the students engaging with the text in Hebrew. Far from it. In fact, I found that the students were far better prepared than if their sole task had been to read through the text ahead of class, because they came to the classroom with a clear sense of the philological and interpretive issues that they considered particularly important and with a readiness to discuss them. Meanwhile, by placing the emphasis on the students’ engagement with the text ahead of class time, rather than on their performance during a round of translation, the pedagogical focus remained firmly on how the students could learn to apply their knowledge of Hebrew to deepen their analysis of the psalm. It also created an open and trusting learning environment that led to highly creative outcomes. The students often came to class with detailed handouts in which they laid out the research they had done on the psalm and raised key interpretive questions that remained for them. Students also presented their findings in other creative ways; for instance, when we were discussing Psalm 68 and the theory of Yhwh’s southern origin, one student mapped the potential sites of the locations mentioned in the psalm (and related extra-biblical sources) in an interactive Google Earth map.

Charles Dai’s Google Map listing (potential) locations of certain places mentioned in Psalm 68 and in the secondary readings assigned as homework

Overall, one of the greatest benefits of the flipped classroom format was that it allowed me as a teacher to play to the students’ individual strengths, while also challenging them as a group to create something greater than they could achieve individually. To cite one noteworthy example: one of the students who took the seminar is Canadian and was the only member of the class who had good reading knowledge of French. In the class devoted to Psalm 68, she took responsibility for reading relevant portions of the recent monograph by Fabian Pfitzmann Un YHWH venant du Sud? and for presenting to the class its main argument concerning the compositional history of the psalm.

Jessica Patey’s handout presenting key insights about the compositional history of Psalm 68 gleaned from Fabian Pfizmann, Un YHWH venant du Sud? De la réception vétérotestamentaire des traditions méridionales etdu lien entre Madian, le Néguev et l'exode (Ex-Nb ; Jg 5 ; Ps 68 ; Ha 3 ; Dt 33), Orientalische Religionen in der Antike 39 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2020).

The result was a rich discussion of a non-English scholarly work that I could not have assigned as a set reading, and which would have otherwise remained virtually inaccessible to the other students. The student who presented her analysis of the monograph was also empowered to effectively teach the materials to the class, while also being challenged to field questions from her peers and to integrate her individual findings with what others had presented concerning other aspects of the psalm.

The collective results of the students’ exegetical research pushed our collective understanding of the psalm far beyond what I could ever have imparted in a lecture format; it certainly went well beyond what we would have achieved had we stuck to the “circle translation” method. The result was a collective commentary on select psalms that was creative, insightful, and rigorous, in which the students put their Hebrew to work in critically analyzing portions of scripture and flexed their muscles as budding exegetes. Moreover, the students experienced what research really feels like – approaching a biblical passage from various angles, moving between different levels of analysis, and seeking to integrate diverse findings to gain an overarching sense of the text in its literary and historical contexts.

Julia Rhyder is Assistant Professor of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at Harvard University.