Students rarely describe the final exam as a positive experience. For many, it is an intense time of stress and anxiety as they frantically attempt to memorize a semester’s worth of learning. The usefulness of final exams is a frequent topic of conversation especially with increased focus on students’ mental health. There are also legitimate doubts whether students retain sufficient knowledge of material long-term, prompting questions regarding the effectiveness of such assessment.[1] In my own experience, even one month later my students have forgotten key terms and concepts they aced on a recent exam. I began to question how I could reimagine the final exam to lessen my students’ anxiety. What would happen if I were to flip the traditional model on its head? Instead of the final exam serving as the ultimate gauge of their knowledge, what if students encountered testing as a form of play and friendly competition before finals? This led me to gamify the exam.

Gamification is the transference of game-based strategies to non-game contexts. There are many advantages to adopting games in the educational environment, including increased student engagement, motivation, and social bonds. In particular, games facilitate a healthier approach to learning that allows for failure and the expectation that one learns through repetition. Students are more likely to take risks when the stakes are low and allow themselves to see mistakes as part of the learning process. This is an important mindset shift from the perfection embedded in traditional academic evaluations. As Patrick Buckley and Elaine Doyle state, “A key objective of most games is not to forbid failure but to develop a positive relationship with it.”[2] Gamification can involve introducing games into individual classes or instructors redesigning the whole course as a game with points to be collected. My choice to gamify the exam also resulted in changes to the whole course since the readings and assignments were scaffolded to the final evaluation. However, before students even get to the final exam, they need to create the game.

Setting up the Game: Retrieval Practice

My “Monsters in the Bible” class is popular at our school, as students love digging into the complexities of monster theory. But what really excites them is their final project – where they must design a trivia game based on class lectures and readings. I have based this activity on the real Professor Noggin’s Card Games geared towards elementary children. The original game has 30 cards devoted to a specific subject like “Geography of Canada” or “Earth Science.” Each card is organized around a specific topic (e.g. Nunavut) with a picture and on the reverse two sets of three questions (i.e. multiple choice, true or false, etc.) of varying difficulty.

The gameplay is simple. A student rolls the dice and the player to their left picks up a card from the central deck and reads the selected question. If the first student gets the correct answer, they get to keep the card; otherwise, it is returned to the bottom of the deck. The player with the most cards once the deck is exhausted wins the game. To add a bit of competition, there is also a “wild” question incorporated haphazardly through the deck called “Noggin’s Choice.” If a student rolls this option, then they can steal a card from another player and the card with “Noggin’s Choice” is returned to the central deck. The goal of the game is to learn through repetition rather than testing a student’s previous knowledge. It is expected that students likely will not get the questions right the first time. However, as they play through the deck, their ability to remember the answers increase as they encounter these cards multiple times. Students are enabled to take chances and accept their own gaps in knowledge in such a low-risk environment.

I have adapted my own “Monster” game from the original with a layered approach that guides students from course material to the final exam. This is designed to give students multiple points of contact with the readings, lectures, and discussions to avoid feeling overwhelmed. First, each student is assigned two different lectures from the semester that include the readings and the PowerPoint from the lesson. Students are required to annotate the assigned articles each week so there is already some established familiarity. Secondly, students make 12 trivia cards for their two assigned lessons, with each card containing four questions. These trivia questions include a mixture of multiple choice, fill in the blank, and true or false.[3] By combing through the articles and lectures for their two classes in advance, they are starting to study and activate their long-term memory. This strategy known as retrieval practice – has been shown as far more effective than rereading study notes.[4] For their final exam, I promise the class that at least 75% of student questions will be used for the trivia section.[5] Students at first are a bit incredulous since they will potentially walk into the exam knowing many of the questions and answers in advance. This approach to flipped assessment stems from my own experience of encountering how little information students retain from traditional models of testing. In this way, students not only know the material, but they have designed their own assessment.

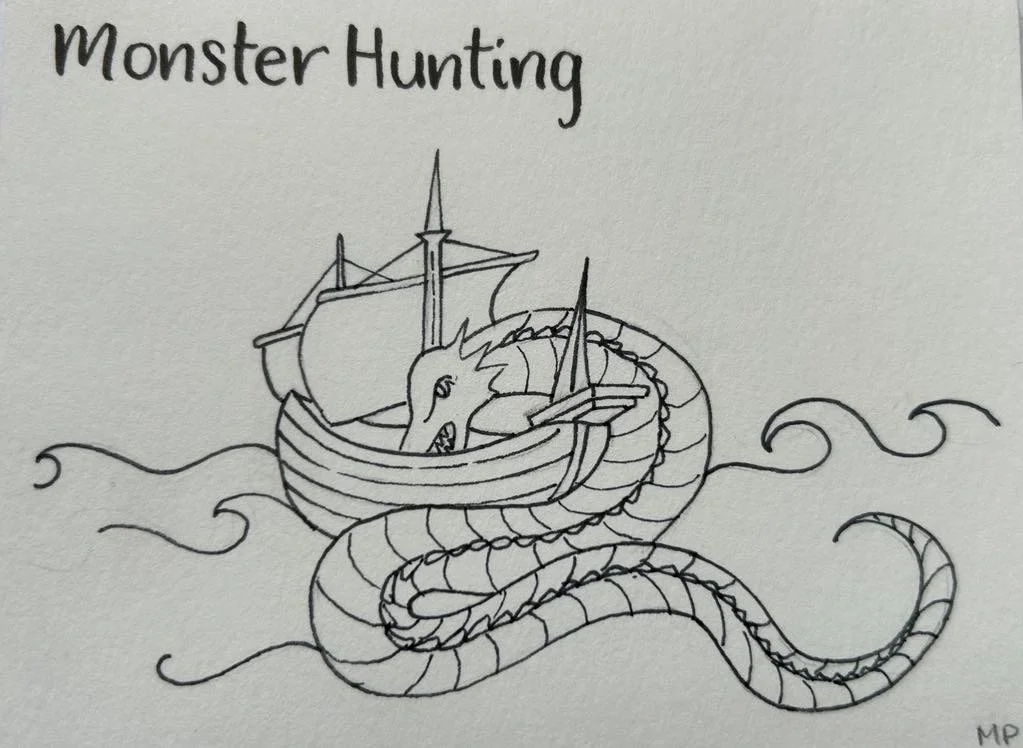

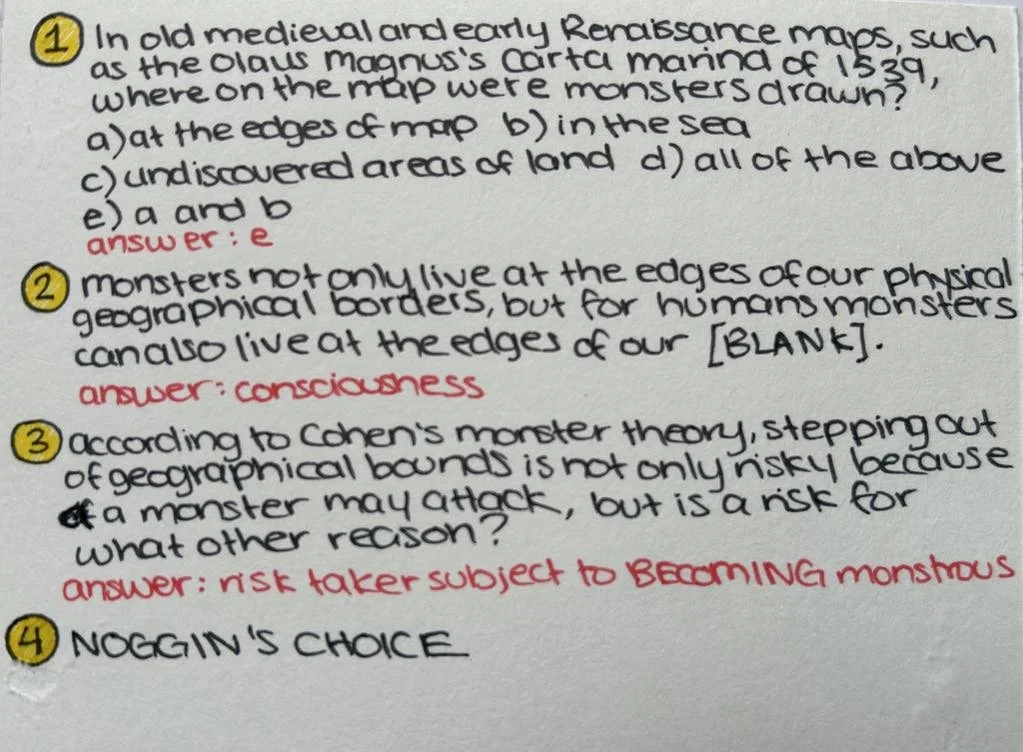

The best trivia cards are those centered around a theme – helping students to remember important parts of the lecture and readings. For example, one of my students organized her cards based on my PowerPoint slides, both in the images and questions. The student’s card is simplified but bears enough similarity to trigger associations with the PowerPoint lecture. Moreover, the title of the card “Monster Hunting” mimics that week’s lesson “Hunting for Monsters” furthering the thematic overlap.

In How People Learn, an effective strategy for increasing retention of information involves “clustering,” defined as “organising disparate pieces of information into meaningful units.”[6] On the reverse of the card, the student has used a combination of different questions drawing from both the lectures and readings.

Thus, each card represents an opportunity for students to make sense of the readings and classes by grouping similar themes together. Rather than each student synthesizing and making notes of the individual readings and lectures, their collective games allow for collaborative and shared work.

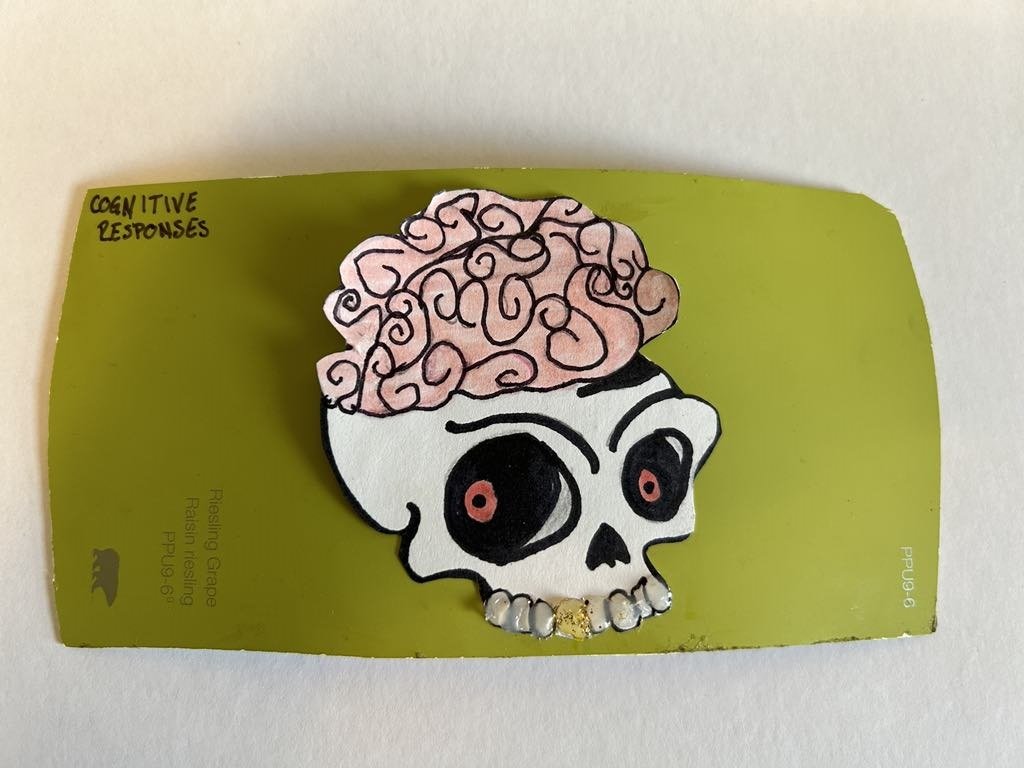

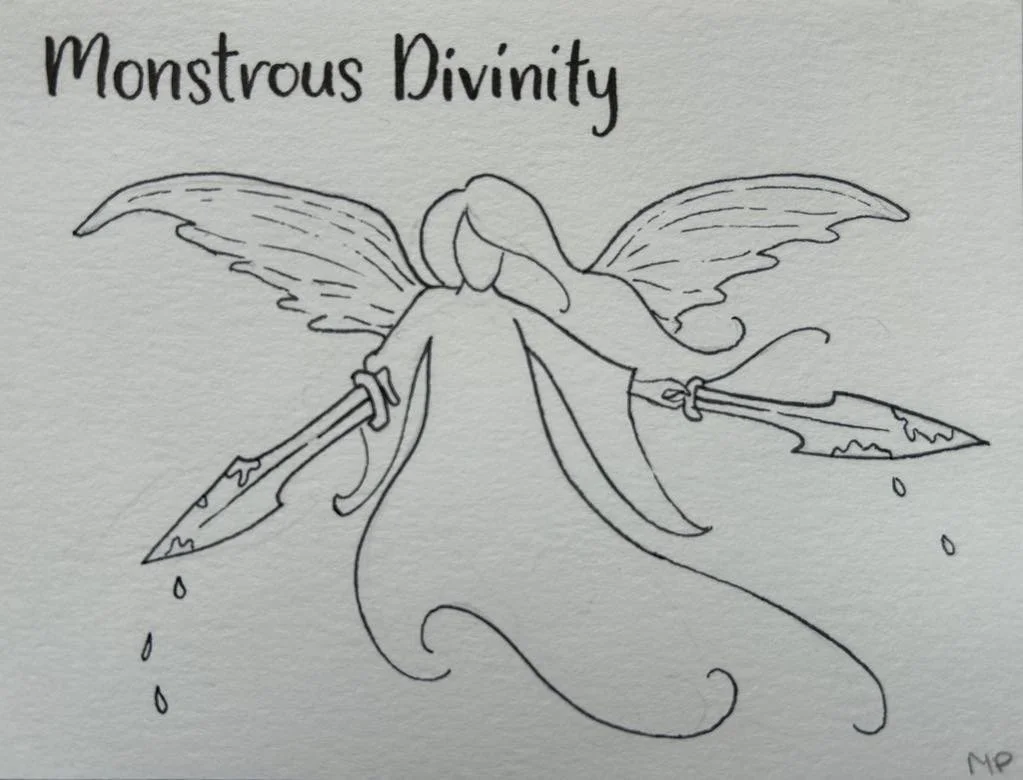

The inclusion of an image or symbol has proven effective for students’ enjoyment and retention of information. Students are excited to share their work with others and on game day they immediately pore over the cards – appreciating the creativity of their peers’ labour. Beyond aesthetics, these visual aids help spark students’ memory. Pairing words and images for memory retention is common in the college classroom but it is often a passive activity as instructors alone choose the images.[7] However, in this exercise, students have complete ownership over their cards, resulting in a diversity of ways that they make meaning between word and image. Students are predictably worried especially if they doubt their creativity, but even simple symbols printed from the internet are just as effective.

The following examples illustrate the range of student abilities and originality.[8] Crystal Heppner used commonly available paint chips for her cards but also inventively employed 3-D images. As a social science major, she brought her interdisciplinary interest in dialogue with a biblical studies course by focusing on “cognitive responses” to the monstrous.

Another student, Makayla Plett used a minimalist approach by simply drawing her beautiful images on plain white cardstock.

Both methods are highly effective, and students find it reassuring to see older student examples. For those who fear that their perceived lack of artistic talent may affect their grade, I remind them that even simple symbols or icons can be incredibly helpful. The pictures are important, but it is their connection to the theme of the card and how they spark memory of the material that matters most.

Summary: Playing the Game

I reserve the last two classes of the course for “game day,” when students bring both sets of their cards and arrange them at the front of the classroom. Students form groups of 4-5 students and grab a few sets of trivia games. They play through the deck following the original rules of the card game. Devoting two full classes to the game is important as it reinforces for students the impact of studying in advance for their final exam. Student anxiety is lessened especially on the second game day when they realize how much information they have retained. There is also something unique about the tactile nature of the game and the social aspect of it.[9] The collaborative aspect of making these games for each other and playing them together reinforces a sense of comradery and support.[10] In the world of gamifying the classroom, this exercise is quite simple and one might expect students to find it boring. However, after teaching this course three times, I have witnessed the game’s continued longevity and popularity. Recently, former students met again as a group to play their games a full year after the course simply for their own enjoyment.

Although students might report a dislike of final exams, there is evidence that testing improves their retention of material. In this exercise, students are not simply studying and rereading material but testing themselves repeatedly.[11] The process of making the cards and even coming up with helpful questions for their peers is a challenging task. One area I aim to improve in the future is providing greater clarity on how to write good questions and what information should be prioritized from the readings and lectures. There is an overwhelming amount of information and detail that students must wade through as they prepare their card games. Bringing games into the classroom builds skills but also increases students’ enjoyment and satisfaction. The stakes are raised since their work affects not only them personally but every other student who is relying on their efforts. Gamifying the exam might not ease all the stress, but it encourages healthy habits of studying and bolsters students’ confidence.

Bibliography

Buckley, Patrick, and Elaine Doyle. “Gamification and Student Motivation.” Interact. Learn. Environ. 24.6 (2016): 1162–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2014.964263.

Callender, Aimee A., and Mark A. McDaniel. “The Limited Benefits of Rereading Educational Texts.” Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 34.1 (2009): 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2008.07.001.

Ebersbach, Mirjam, Maike Feierabend, and Katharina Barzagar B. Nazari. “Comparing the Effects of Generating Questions, Testing, and Restudying on Students’ Long-Term Recall in University Learning.” Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 34.3 (2020): 724–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3639.

Khanna, Maya M., Amy S. Badura Brack, and Laura L. Finken. “Short- and Long-Term Effects of Cumulative Finals on Student Learning.” Teach. Psychol. 40.3 (2013): 175–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628313487458.

National Council Research (U.S.): Committee on Developments in the Science of Learning. How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition. Edited by John Bransford, Ann L. Brown, and Rodney L. Cocking. Washington: National Academies Press, 2000.

Roediger III, Henry L., Pooja K. Agarwal, Mark A. McDaniel, and Kathleen B. McDermott. “Test-Enhanced Learning in the Classroom: Long-Term Improvements from Quizzing.” J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 17.4 (2011): 382–95. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026252.

Whitley, Cameron T. “A Picture Is Worth a Thousand Words: Applying Image-Based Learning to Course Design.” Teach. Sociol. 41.2 (2013): 188–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092055X12472170.

[1] Aimee A. Callender and Mark A. McDaniel, “The Limited Benefits of Rereading Educational Texts,” Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 34.1 (2009): 30–41, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2008.07.001; Mirjam Ebersbach, Maike Feierabend, and Katharina Barzagar B. Nazari, “Comparing the Effects of Generating Questions, Testing, and Restudying on Students’ Long-Term Recall in University Learning,” Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 34.3 (2020): 724–25, https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3639.

[2] Patrick Buckley and Elaine Doyle, “Gamification and Student Motivation,” Interact. Learn. Environ. 24.6 (2016): 1164, https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2014.964263.

[3] I have simplified the format of the original game.

[4] Henry L. Roediger III et al., “Test-Enhanced Learning in the Classroom: Long-Term Improvements from Quizzing,” J. Exp. Psychol. Appl. 17.4 (2011): 382, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026252.

[5] The final exam has two parts: (1) trivia based on the students’ games; (2) an essay question.

[6] National Council Research (U.S.): Committee on Developments in the Science of Learning, How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition, ed. John Bransford, Ann L. Brown, and Rodney L. Cocking (Washington: National Academies Press, 2000), 96.

[7] Cameron T. Whitley, “A Picture Is Worth a Thousand Words: Applying Image-Based Learning to Course Design,” Teach. Sociol. 41.2 (2013): 188, https://doi.org/10.1177/0092055X12472170.

[8] Student examples used with permission.

[9] I discovered during the lockdowns of 2021 that this game adapts well to an online format. Students had the choice of making physical cards and taking pictures to put on a PowerPoint. Or they could design PowerPoint slides as cards. Students then met in breakout rooms and shared their screens to play their games.

[10] Students are also required to provide a list all the questions and answers from their cards in a shared document to allow students to further study before the exam.

[11] Maya M. Khanna, Amy S. Badura Brack, and Laura L. Finken, “Short- and Long-Term Effects of Cumulative Finals on Student Learning,” Teach. Psychol. 40.3 (2013): 176, https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628313487458.