The Masorah of the Cairo Codex of the Prophets in Perez-Castro’s Printed Edition[1]

The following article examines the methods and conventions utilized by F. Perez-Castro's editorial team, who have produced the eight-volume series El Codice de Profetas de el Cairo, which transcribes the contents of the Cairo Codex. This critical series represents more than a decade's worth of work painstakingly presenting the contents of the Cairo Codex in a format that is accessible and which meticulously follows the original manuscript. Beyond transcribing the Hebrew text of the Prophets, the series preserves the Masorah notes and offers editorial footnotes discussing this marginalia when the note is of scholarly concern. To accomplish this task and to shed light on the importance of its preservation through a printed edition, a look at the history and dating of the original manuscript would be beneficial.

Disappearing from direct scholarly access in 1984[2], the Cairo Codex was once believed to be the oldest vocalized manuscript of the Nevi’im to be extant in the 20th Century. The manuscript itself contained nearly 600 pages of text written on gazelle-hide parchment measuring 16 inches long by 15 inches tall. Also included in the manuscript were 14 carpet pages decorated in geometric patterns of small Hebrew text as well as colored inks and gold leaf. The claim for its antiquity begins in the first colophon of the manuscript itself. The author of the colophon claims the text of the manuscript was completed by 896 CE and attributes its authorship to Moshe ben Asher. This dating would indeed make it the oldest extant manuscript of the Hebrew Scriptures. Unfortunately, the colophon’s authenticity is questioned by some.[3]

Much of the early investigation into the authenticity of the Cairo Codex did support the early dating of the manuscript. In one of the first facsimiles made of the manuscript, published in 1971, D.S. Löwinger posits[4] a dating 895-897. Even at this early stage of the investigation, Löwinger notes there were doubts about the authenticity of at least the authorship of Moshe ben Asher.[5] Despite these doubts, scholars as late as the closing of the 20th Century[6], with some prefacing[7], were still espousing the early dating of the manuscript.[8]

Other studies of the writing style of the colophon seemed to support its authenticity,[9] but just as Löwinger predicted in his introduction to the first facsimile of the Cairo Codex in 1971 when he said, “… this problem will ultimately be solved by radioactive analysis,”[10] the debate continued until radio-carbon dating could be performed on the manuscript. The results of the testing place the date of the manuscript at around 990CE.[11] Further scholarship supported this later date, and the colophon was declared a forgery. It was accepted as such by a majority of scholars and remains so today.[12]

Whichever dating the reader finds most persuasive, the importance of the manuscript as one of the earlier copies of the Nevi’im with its robust Masoretic notes is evident. To scholarship’s great benefit, a printed edition was created before the original manuscript was lost in 1984.[13] As noted in the preface to the series,[14] the goal of the Perez-Castro team was not to create a comparative volume that analyzed the differences between the other early manuscripts. Instead, it was to present the text of Cairo on its own in a faithful rendition.

The editorial team first began publishing this series in 1979 with the volume VII, Profetas Menores, as well as the aforementioned Prefacio. The series then published volume I, Josue – Jueces (1980); volume II, Samuel (1983); volume III, Reyes (1984); volume IV, Isaias (1986); volume V, Jeremias (1987); volume VI, Ezequiel (1988); and finally volume VIII, Indice Alfabetico de sus Masoras (1992). These volumes provide a series of tools to help the reader in the study of text and Mesorah. A crucial part of each introduction in the volumes is the Abreviaturas y Siglas Utilizadas en las Masoras. This simple list provides a quick reference to nearly all of the Masoretic abbreviations used within the volume.

Figure 1[15]

As these abbreviations are often common between manuscripts, this list is not only useful for deciphering the Masoretic notes of Cairo but would also aid in the study of other manuscripts and their Masorah.

The main body of each volume is comprised of a transcription of the consonantal Hebrew text typed onto the page. In a show of fantastic dedication, the vowel pointing on the Hebrew text was later added by hand. The text itself does not precisely follow the placement found in the manuscript. The original often renders the Hebrew in three columns oriented in the standard right to left justification. When reading the text, one may notice a series of mem-im (מ). These indicators are used as space fillers to indicate that the manuscript did not have a space at this position. This system is needed because, at other points in the recreation of the text, the editorial team renders the Hebrew text in the same way it is presented in the original manuscript.

Figure 2[16]

Figure 3[17]

Underneath the text itself are two apparatuses. One is a rendering of the Masorah parva notes as well as the Masorah magna lists, and the other is a listing of clarifications, footnotes, or additional explanatory notes. The Masorah notes found within the first apparatus collate the Masorah parva notes found in the margins of the original manuscript into a list ordered by the appearance of the noted word within the Hebrew text. If the observed word also has an associated Masorah magna note, it is rendered in the same position on the list.

Perez-Castro utilizes a few techniques to organize the list of Masoretic notes in a way that makes it easy to follow and to quickly reference when studying the text. The note is broken up into verses, and the verse numbers are printed at the beginning of each list. If the list contains multiple verses, a double bar line ( || ) is utilized to divide the list, after which the new verse number is indicated. Within a note, reading right-to-left, the full vowel pointed, and cantalized word in question is reprinted, followed by a left square bracket ( [ ). If the note is a Masorah parva note, the letters "MP" are used to indicate this, and the actual Masorah parva note is printed. Notes within the same verse are divided by a single bar line ( | ). If the note is a Masorah magna note, the letters "MM" are used to indicate this, and the catchwords[18] are rendered in their original order. The editorial team helpfully resolves the catchwords to the biblical references and places them in parenthesis after the words. The letters "MP" follow the Masorah magna list if the associated word also has a Masorah parva note on the same page of the manuscript.

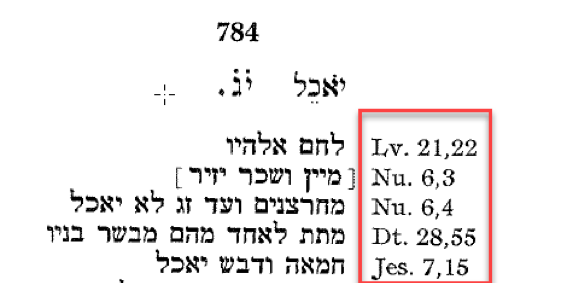

Figure 4[19]

In some cases, the word in which the original manuscript marks having Masoretic interest does not have an associated Masoretic note. Instead, it is merely listed as part of a specialized list pointing out unique aspects. One particularly tricky example is that of the word לַשָּׁרוֹן found in Joshua 12:18. The Hebrew text itself is rendered in a stylized word alignment with the Masoretic list in question being located in a large gap between words within the verses. The style of the text is rendered faithfully within the body of the printed edition, but the interstitial Masoretic list is brought down to the first apparatus. Here the editorial team indicates the lack of an actual Masoretic note by using an empty set of curly braces ( { } ). Though there is no indication that this is the purpose of the list, it becomes clear from merely looking at the words highlighted that it is a list of words that end with a vav and a final nun (ון). The apparatus does not recreate the stylistic way in which the list is rendered within the text. It merely reproduces the catchwords along with their biblical references and then the highlighted word at the end.

Figure 5[20]

Volume VIII[21], the last in the series and the last to be published, acts as an extended index of the Masorah magna and Masorah parva found in the Cairo Codex and rendered in alphabetical order. This one, of all the volumes, offers the most value to scholars of Masoretic notes as it provides a wonderfully quick way to access every note within the collected volumes. The index is arranged by grouping the words alphabetically by their roots. Then, within the root groupings, words are listed according to their forms, as found in the biblical text. Each entry provides not only the biblical reference but also an indication of being either (or both) a Masorah magna (MM) or a Masorah parva (MP) note. For those interested in knowing the location of each note from a long list of MP notes, this index provides a time-saving reference for which further study is made all the easier. If a Masoretic note references a phrase, the editors have helpfully provided a cross-reference system pointing the user back to the main entry found under the first one in the phrase.

While volume VIII was the final volume in the series lead by Perez-Castro, the editorial team, namely Emilia Fernandez Tejero and Maria Teresa Ortega Monasterio, went on to publish two further volumes. These works separate the Masorah magna[22] and Masorah parva[23] into two distinct books. As the titles would indicate, they list the various Masorah notes into a quick and easy reference volume when dealing with the Masorah notes found within the Cairo Codex. The extended works go beyond the notes listed in the Perez-Castro volumes and include the notes not directly associated with words highlighted in the original manuscript. This includes lists put into the margins of the manuscript formed into geometric shapes.[24]

Figure 6[25]

Figure 7[26]

Overall, this series is a monumental contribution to scholarship, which cannot be overstated. The care and detail which this series places on the recreation manuscript text is unparalleled, and with the loss of the actual manuscript, the work is made even more critical. This volume series is one of the last works created by scholars who have seen the actual physical manuscript able to provide a detailed recreation of the text even in places where the extant facsimile copy remains illegible. The only problem with the volume series is its lack of popularity among library staff.[27] Hopefully, as more scholars pick up the mantle of Masoretic studies, a resurgence of interest in these excellent volumes will yield a second printing.

[1] The following article does not reflect a word-for-word recording of the work presented at the SBL Annual Meeting. The talk itself was done extemporaneously with the help of presentation slides. The outline of the talk follows the basic flow of this article. Where appropriate, excerpts from the presentation slides are included here as figures.

[2] The whereabouts of the Codex is under some dispute and no solid evidence exists as to its current location. Speculation has narrowed down the location of the text to either Egypt or Israel with the individual or organization in possession of it keeping it out of public view. Nadine Epstein, “The Mystery of the Cairo Codex: on the Trail of an Ancient Manuscript,” Moment, January 2016, Accessed April 3rd, 2017. https://www.thefreelibrary.com/-a0442453992

[3] It should be noted that at the SBL 2019 Annual Meeting a vigorous discussion ensued after the presentation on the dating of the manuscript. It was made clear that total consensus has not been reached within scholarship.

[4] D.S. Löwinger, ed., Codex Cairo of the Bible. From the Karaite Synagoge at Abbasiya. The Earliest Extant Hebrew Manuscript Written in 895 by Moshe Ben Asher. A limited facsimile edition of 160 copies. 2 vols. (Jerusalem: Makor Publishing LTD, 1971), 1. In both the Hebrew and English summary introduction, Löwinger cites other scholars and dates proposed at the time. The primary citation he makes in from R Gottheil in Some Hebrew Manuscripts in Cairo. (JQR, 1905), 640, Ms. 34.

[5] Ibid., 8-10.

[6] Martin Jan Mulder, “The Transmission of the Biblical Text,” in Mikra: Text, Translation, Reading, and Interpretation of the Hebrew Bible in Ancient Judaism and Early Christianity, ed. Martin Jan Mulder and Harry Sysling (Peabody, Mass.: Baker Academic, 2004), 115. This essay was originally published in 1988 by Van Gorcum publishers in Assen, Netherlands as part of a series Compendia rerum judaicarum ad Novum Testamentum. Section 2, The Literature of the Jewish people in the period of the second temple and the Talmud.

[7] E. J. Revell, “The Codex as a Representative of the Maoretic Text,” in The Leningrad Codex: A Facsimile Edition, ed. Astrid Beck, David Freedman, James Sanders. (New York: Brill Academic Publishers, 1998), xxxi. Here Revell claims that the 896 CE dating found in the colophon is in reference to the consonantal text whereas the nekudot was added later in the style of ben-Naftali as recorded in Kitāb al-Khilaf.

[8] Israel Yeivin, Introduction to the Tiberian Masorah, trans./ed. E. J. Revell in Masoretic Studies 5 (Missoula: Scholars Press, 1980), 21.

[9] Paul Kahle, The Cairo Geniza. Schweich Lectures, 1941. (London: Oxford University Press, 1947), 97. Kahle suggests that the language of the colophon appears to be a traditionally written Karaite styled manuscript.

[10] Löwinger, ibid., 10.

[11] Malachi Beit-Arié; Mordechai Glatzer; Colette Sirat, Codices Hebraicis litteris exarati quo tempore scripti fuerint exhibentes, Monumenta paleographica medii aevi. Series hebraica. (Turnhout: Brepols, 1997), 28.

[12] דוד לייאנס, המסורה המצרפת : דרכיה וסוגיה : על פי כתב־יד קהיר של הנביאים [David Lyons, The Cumulative Masora: Text, Form and Transmission with a Fascimile Critical Edition of the Cumulative Masora in the Cairo Prophets Codex]. (Be’er-Sheva’: University Ben-Guryon ba-Negev, 2000), vii, 4-5.

[13] Nadine Epstein, ibid.

[14] F. Perez-Castro, et. al., El Codice de Profetas de el Cairo Prefacio, Textos y Estudios “Cardenal Cisneros” de la Biblia Poliglota Matritense, (Madrid: Instituto “Arias Montano”. CSIC, 1979), 22.

[15] F. Perez-Castro, et. al., El Codice de Profetas de el Cairo Profetas Menores, Textos y Estudios “Cardenal Cisneros” de la Biblia Poliglota Matritense, (Madrid: Instituto “Arias Montano”. CSIC, 1979), front matter.

[16] Cairo Codex, Judges 5:16-19

[17] F. Perez-Castro, et. al., El Codice de Profetas de el Cairo Josue – Jueces, Textos y Estudios “Cardenal Cisneros” de la Biblia Poliglota Matritense, (Madrid: Instituto “Arias Montano”. CSIC, 1980), 147.

[18] During the Masorah sessions at the SBL Annual Meeting 2019, a running discussion was had during the question and answer portions as to what scholarship should call these words and phrases. Terms such as `catchword`, `siman`, `simanim`, `general indicators` and others have been offered. I choose here to use the term catchword and the purpose of the recorded words in the manuscript are to point do different biblical references using common words or phrases found in those verses.

[19] F. Perez-Castro, et. al., El Codice de Profetas de el Cairo Josue – Jueces, Textos y Estudios “Cardenal Cisneros” de la Biblia Poliglota Matritense, (Madrid: Instituto “Arias Montano”. CSIC, 1980), 73.

[20] F. Perez-Castro, et. al., El Codice de Profetas de el Cairo Josue – Jueces, Textos y Estudios “Cardenal Cisneros” de la Biblia Poliglota Matritense, (Madrid: Instituto “Arias Montano”. CSIC, 1980), 72.

[21] F. Perez-Castro, et. al., El Codice de Profetas de el Cairo Indice Alfabetico de sus Masoras, Instituto de Filologia del CSIC, (Madrid: Departmento de Filologia Biblica y de Oriente Antiguo, 1992).

[22] Emilia Fernandez Tejero, La Masora Magna del Codice de Profetas de el Cairo: Transcripcion alfabetico-analitica, Instituto de Filologia del CSIC, (Madrid: Departmento de Filologia Biblica y de Oriente Antiguo, 1995).

[23] Maria Teresa Ortega Monasterio, La Masora Parve Del Codice de Profetas de el Cairo: Casos lêṯ, Instituto de Filologia del CSIC, (Madrid: Departmento de Filologia Biblica y de Oriente Antiguo, 1995).

[24] The Cairo Codex manuscript has many ornate lists that form unique but very angular and geometric shapes.

[25] Cairo Codex, Hosea 14:5.

[26] Emilia Fernandez Tejero, La Masora Magna del Codice de Profetas de el Cairo: Transcripcion alfabetico-analitica, Instituto de Filologia del CSIC, (Madrid: Departmento de Filologia Biblica y de Oriente Antiguo, 1995).

[27] As I was preparing for this presentation and article, no single library within the New York City area and a complete set. I was lucky enough to have access to individuals that have personal copies of the volumes and able to borrow theirs in preparing the figures for the slide presentation delivered at the SBL Annual Meeting 2019.