AJR is happy to host publish remarks delivered as part of a review panel for Dr. Meredith J. C. Warren’s recent publication, Food and Transformation in Ancient Mediterranean Literature.

Read MoreBeyond Canon: An Introduction to the Project

Even if the fourth and fifth centuries may have brought important changes for large parts of the “Christian” movement (or better: the different groups of Christ followers), the production of texts which reasonably can be labelled “Christian apocrypha” did not simply stop. To the contrary, with some genres the production of texts seems to have exploded.

Read MoreSenator Marcellus as an Early Christian Role Model: The Destruction and Restoration of a ‘Statue of the Emperor’ in Acta Petri 11

Marcellus might be seen as a role model of how to negotiate a relationship with Roman authorities, on the one hand, and with the Christian faith and a Christian life, on the other.

Read MoreSt. Thomas the Apostle in the Armenian Church Tradition

Therefore, while in general the Armenian apocrypha have rarely been the focus of interest, the acts/martyrdoms of the founders of the Armenian Church—which, in fact, were not considered ‘apocryphal’ in medieval times—can boast of being at the center of great interest for scholars.

Read MoreVisual Representations of Early Marian Apocryphal Texts: Some Notes on the Top Register of the Triumphal Arch at Santa Maria Maggiore

While there may be books that “should not be read,” does that injunction necessarily equate to art that should not be painted or viewed?

Read MoreRetelling Thomas’ Story: Reception of the Apocryphal Acts of Thomas in the Synaxarion of the Liturgical Thomas-Feast

The indisputable presence of information from the Apocryphal Acts of Thomas in the Synaxarion of the Thomas-Feast (concerning especially the beginning of the Thomasine mission in India and his martyrdom there) proves the liturgical functionality of the reception of this apocryphal text.

Read MoreManuscripts Beyond the Canon

In one sense manuscripts play an obvious role in the research carried out on apocryphal and other early Jewish and Christian writings beyond the canon. They are the primary arbiters of the texts or works that are the main focus of most affiliated scholars, even if most people tend to rely on critical editions and translations when they exist.

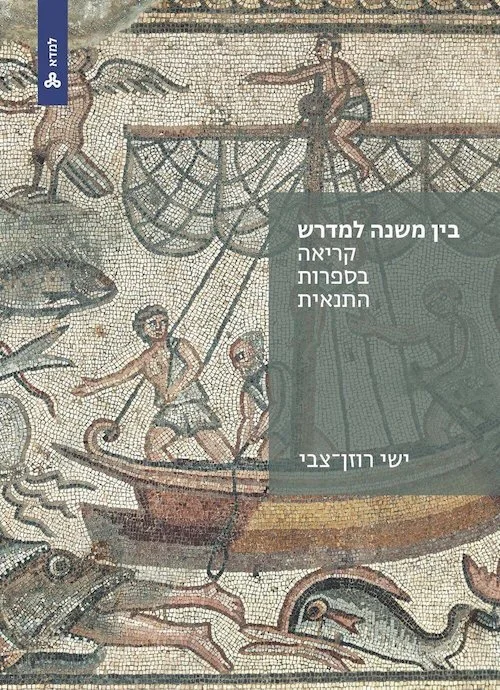

Read MoreBook Note | Between Mishna and Midrash

“Close reading, suggests Rosen-Zvi, resembles micro-historical study since in both cases a close look at one detail reveals large social and cultural processes that cannot be seen from a wider perspective.”

Read MoreBook Note | Enoch From Antiquity to the Middle Ages

…[O]ne of the most valuable contributions are the plentiful insights throughout this volume that have implications for a wide variety of fields, ranging from antiquity to the medieval period. And, while there are no doubt plentiful insights with regard to Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, a number of observations throughout this work also hold implications for the field of Ancient Mesopotamian religion and its relation to later traditions.

Read MoreBook Note | Time in the Babylonian Talmud

Kaye suggests that time as imagined in the BT is best represented by Wassily Kandinsky’s painting, Several Circles (1926). According to Kaye, the painting’s circles of various sizes and colors represent various moments; these moments, as circles, interact both temporally and spatially and are spread across the canvas non-linearly.

Read MoreSBL 2019 Review Panel | Food and Transformation in Ancient Mediterranean Literature

Hierophagy is the word I chose to describe this genre of transformational eating. I define hierophagy as a mechanism by which characters in narrative cross boundaries from one realm to another through ingesting some item from that other realm.

Read MoreSBL 2019 Review Panel | Food and Pharmaka

Warren’s book thus represents a significant breakthrough in the scholarly understanding of commonalities in the religion and philosophy of ancient Mediterranean societies.

Read MoreSBL 2019 Review Panel | Seeing or Tasting? Human’s Perception of the Heavenly World in Hellenistic Jewish Writings

Taste is more than a physical sense of perception. Since antiquity, food as well as its taste can be used as a metaphor in order to express evaluations and aesthetic judgments. As an ability to discern pleasure and displeasure, taste “has been applied figuratively to perception, judgment, speech, and conduct.”[1] Moreover, as Meredith Warren states in the beginning of her innovative volume:

In certain cases, eating brings about unexpected results, such as the transformation of the eater or the opening of windows into another realm.[2]

At the beginning of her lucid study, Warren identifies a narrative pattern she calls “hierophagy,” which, in her words, is:

part of the literary toolbox used by ancient authors to transmit a certain understanding of the relationship between God and mortals, heaven and earth.[3]

By ingesting some items from an otherworldly realm – food or non-food items, such as book scrolls or rosaries and the like – a human eater is physically and ontologically transformed. “Hierophagy,” as Warren summarizes, “binds the eater to the place of origin, transforms her or him, and transmits knowledge.”[4] She proves the existence of this narrative pattern or motif by a close reading of five texts from Jewish, Christian, and Roman contexts and from one mythological tradition represented by the Hymn to Demeter and Ovid’s Metamorphosis.

Warren calls the pattern a genre in order to underline that she restricts the scope of her question to the literary level.[5] For her, “hierophagy” is not a key or window to any ritual or cultic practice that might or might not have been practiced by those who wrote the respective stories. However, as Warren likewise notes, genre is a slippery term in scholarship. In Brill’s New Pauly, Richard Hunter summarizes the discussion in the following way:

Literary genres are the result of literature being divided into groups. Poetry and/or prose are classified by a culture or its interpreters, based on the principle of similarity – the occasion on which they are presented, audience, topic, musical style, etc. The concept of ‘genre’ has been culturally determined since the dawn of history, because the meaning of a work depends not least on the extent to which the audience perceives it as similar to or different from earlier works. Within a given culture, different groupings may be preferred at different times. Moreover, genre categories that may appear logical to modern-day scholars may not necessarily correspond to those of ancient times.[6]

In other words, genre is more than a sample of features in a given text. Genre rests on the notion of a given audience that uses the text for specific purposes. Former German scholars coined for this social function of text the expression Sitz im Leben.

Many different Sitze im Leben can be assumed for the texts examined here. For instance, the Homeric Hymn to Demeter might want to publicize as well as harmonize by writing the cultic drama celebrated in the mysteries at Eleusis, while Ovid’s version incorporates Greek myth into Roman tradition. Fourth Ezra’s final vision might legitimize seventy-two new sacred books as inspired Scriptures, while Revelation may comfort a suppressed group of endangered martyrs in the struggle against Emperor Cult. Most texts might have more than one Sitz im Leben, a phenomenon that can be proven for Joseph and Aseneth. Some readers of Joseph and Aseneth studied this ancient Jewish novel about Josephs Egyptian wife for entertainment. Or, in their interest in the biblical story of Joseph, others might have looked for a religious version of an ancient novel, while others might have argued with this text for an incorporation of non-Jews into Israel, while still others tried to convince non-Christian (women) that salvation rests in Joseph-Christ alone. In the case of Joseph and Aseneth, we actually know of readers who interpreted this text in such different ways in the history of its reception.[7] In short, I would not call hierophagy a genre but a motif or pattern that can embellish different genres of texts.

As Warren notices, the motif or pattern of hierophagy applies to more texts than she is able to analyze in her book.[8] Greek infant Gods are nourished by nectar and ambrosia. Human beings who come in contact with these heavenly substances become immortal.[9] One can find an early and famous example for this idea in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter as well. The Goddess in the guise of a wet-nurse nourishes and anoints the son of Metaneira, queen of Eleusis, with ambrosia and would have turned him into a god, if his curious and worried mother had not stepped in and interrupted his transformation.[10]

The idea is also known and shared by Jewish thinkers.[11] Jewish wisdom correlates ambrosia with manna.[12] And manna is the same as the food of angels.[13] Nectar, ambrosia, and manna can be expected in the paradise to come at the end of time.[14] Nectar and ambrosia fill the promised land just as much as eschatological paradise.[15]

The effect of tasting manna, however, might surpass the divine immortality promised ny ambrosia and nectar. Philo allegorizes Moses’s pledge to the king of Edom in Numbers 20 – that Israel will not “drink water from any well” while passing through Edom – with the rhetorical question:

shall we on whom God pours as in snow or rain-shower the fountains of His blessings from above, drink of a well and seek for the scanty springs that lie beneath the earth, when heaven rains upon us ceaselessly the nourishment which is better than the nectar and ambrosia of the myths?[16]

In Philo’s view, manna definitely surpasses nectar. However, to philosophers like Philo, Greek and biblical mythology causes some logical problems. Aristotle, an important figure for Philo’s thought, makes the critique explicit:

There is a difficulty, as serious as any, which has been left out of account both by present thinkers and by their predecessors: whether the first principles of perishable and imperishable things are the same or different. For it they are the same, how is it that some things are perishable and others imperishable, and for what cause? The school of Hesiod, and all the cosmologists, considered only what was convincing to themselves, and gave no consideration to us. For they make the first principles Gods or generated from Gods, and say that whatever did not taste of the nectar and ambrosia became mortal – clearly using these terms in a sense significant to themselves; but as regards the actual application of these causes their statements are beyond our comprehension. For if it is for pleasure that the Gods partake of them, the nectar and ambrosia are in no sense causes of their existence; but if it is to support life, how can Gods who require nourishment be eternal?[17]

By their very nature Gods cannot depend on nourishment. Therefore, as Aristotle states, any eatable item cannot mark the borderline between the earthly and heavenly realm. Many Jewish writers agree and argue that angels do not eat.[18]

Yet two biblical texts contradict this assumption. The first text is Genesis 18–19. The heavenly guests appearing at Mamre eat from the curds, milk, and the calf that Abraham and Sara offer them and later also take part in Lot’s drinking party, eating the unleavened bread Lot served them.[19] Yet those who belong to the heavenly realm cannot consume food or drink in a corporeal way.[20] Therefore, those who later interpret Gen 18–19 regularly argue that these angels only seem to eat and drink. In Josephus’s renarration, the visitors made Abraham believe that they did eat.[21] For Philo, in contrast:

“they ate” symbolically [symbolikōs συμβολικώς] and not of food, for these happy and blessed natures do not eat food or drink red wine, but it is (an indication) of their readiness in understanding and assenting to those who appeal to them and put their trust in them.[22]

The second problematic verse for ancient interpreters is Exod 24:11. While angels appearing on earth are easily able to disguise their nature and origin and to manipulate the reception of their appearance, humans cannot. Therefore, human beings who transcend into heaven – in theory – cannot consume any food or liquids there. As the Bible states repeatedly: Moses did not eat and drink during the forty days and nights he stayed with God on Mount Sinai.[23] Moses does eat and drink with Aaron, Nadab, Abihu, and seventy elders of Israel, however, when God made his covenant with his people at Sinai.[24] Why?

Regarding this passage, Philo answers the question (“What is the meaning of the words, ‘They appeared to God in the place and they ate and drank’” [Exod 24:11]) in the following way:

Having attained to the face of the Father, they do not remain in any mortal place at all, for all such (places) are profane and polluted, but they send and make a migration to a holy and divine place, which is called by another name, Logos. Being in this (place) through the steward they see the Master in a lofty and clear manner, envisioning God with the keen-sighted eyes of the mind. But this vision is the food of the soul, and true partaking is the cause of a life of immortality. Wherefore, indeed, is it said, “they ate and drank.”[25]

Because the earth is profane and polluted, the soul has to transcend this world and to migrate to the immediate vicinity of God’s logos. There, the soul is nourished by a clear-sighted and true vision of God. In Philo’s allegorical reading, the shared food served by the Logos is the opportunity to envision God. The Apocalypse of Abraham refers to the same idea when Abraham states on his journey into heaven:

And I ate not bread and drank no water, because (my) food was to see the angel who was with me, and his discourse was my drink.[26]

Both authors agree that food and drink in heaven is a clear-sighted envisioning of God’s angels and her forces. In this way, Philo and the Apocalypse of Abraham do not only solve the logical and theological problems that an ingestion of food would have caused to their imagination of heaven. Rather, these allegorical readings accord with the philosophical notion of the hierarchy of senses. For Plato, Aristotle, and Philo, among many others, gustation occupies the lowest stratum of their taxonomy of sense perception.[27] As Carolyn Korsmeyer shows,

Taste is . . . placed on the margins of the perceptual means by which knowledge is archived; its indulgence must be avoided in the development of moral character, and it perceives neither objects of beauty nor works of art. . . . In virtually all analysis of senses in Western philosophy [and especially Plato and Aristotle] the distance between object and perceiver has been seen as a cognitive, moral, and aesthetic advantage. The bodily senses [i.e., the sense of smell, touch, and taste] are “lower” in part because of the necessary closeness of the object of perception to the physical body of the percipient.[28]

For Plato, eternal souls have to separate themselves from the body in order to ascend to the apprehension of the ideal world of permanence, where truth may be glimpsed mainly by envisioning or hearing. Aristotle discriminates against smelling, touching, and tasting because humans share those senses with animals. Sight, to the contrary, ascends the other sense perceptions, because it permits apprehension of the most information about the world. Second is hearing, because of the importance of learning. Philo reflects both traditions.

For touch and taste descend to the lowest recesses of the body and transmit to its inward parts what may properly be dealt with by them; but eyes and ears and smell for the most part pass outside and escape enslavement by the body.[29]

To me, the most important outcome of Warren’s survey of the hierophagic pattern of Greek, Roman, Jewish, and Christian narratives is exactly this – her observation that myths and narratives indeed remove taste from the margins of the philosophical hierarchy of sense perception. Instead, in the texts she has examined, eating and tasting have become a vital part of the fictive characters’ appreciation of their world.[30] Contrary to leading philosophical traditions and their reception by Philo and other Jewish and Christian writers, in these six texts and traditions the corporeal act of eating as well as the corporeal sense of tasting mediates and conveys contact with the transcendent realm. By tasting food or other heavenly items, a given character is indeed transformed and acts with heavenly knowledge.

So why is it that some texts value taste, a sense relegated to the bottom of the sensory hierarchy by most ancient thinkers, as a sense that enables humans to gain spiritual knowledge? In my view, it is for the same reason that taste will become, soon after these writings, the most prominent sense perception in mystical literature in many religions.[31] Food as well as taste create a symbiosis between the subject and object of sense perception. In gustation, there is no distance or boundary between subject and object, immanence and transcendence, humans and God(s). With the hierophagic patterns or motif, the texts examined by Warren prove themselves to take part in a literary movement that will become – after some more specific literary developments – a branch of Jewish and Christian mysticism.

However, the specific application of the mystical motif of gaining and perceiving knowledge and experiencing transformation through ingesting and tasting heavenly food or other items differs, in my view, from text to text. Persephone remains a god, but change takes place by ingesting the wrong, that is non-divine, kind of food. When Ezra and John of Patmos indulge on the heavenly scroll, it indicates (as it does in the literary prototype of this scene [Ezek 2:8–3:4]) that the following speech is no longer a human word but completely inspired by God.[32] Yet eating, rather than reading or writing a scroll, transgresses a normal or appropriate use of a modern communication medium of that time. Perhaps one can read this as a protest against media technological developments. At least, the incorporation of God’s wisdom by consuming her fruits channels God’s word more directly than reading or writing ever can.[33] The symbolic action expands a combination of metaphors into a new symbolic act. The rosary, on the other hand, eaten by luckless Lucius in Apuleius’s Metamorphosis is the antidote to the magic that earlier had transformed him into an ass. Finally, the taste of cheese or milk, which the steadfast and therefore winning triumphant martyr Perpetua receives from the heavenly shepherd, marks the climax of her climb up the ladder into heaven, an image metaphorically symbolized by her successful fight in the arena of her martyrdom. The depiction of the garden, painted through and in her vision, comes closer to the classical locus amoenus than to the paradise of the Bible.[34]

The most enigmatic text, however, remains Joseph and Aseneth. One reason for the many layers of meaning is most likely a constantly reworking of the text by Jewish and Christian readers and narrators alike.[35] Unlike all the other texts that Warren has examined, eating in Joseph and Aseneth takes place neither in this world nor in another. Rather, the heavenly Anthropos and Aseneth share the honeycomb somewhere in between both realms. Furthermore, Joseph and Aseneth belongs to a group of texts in which the eating of heavenly food does not lead directly to a transformation of the eating character.[36] Aseneth gains her knowledge, called τὰ ἄρρητα μυστήρια τοῦ ὑψίστου (“ineffable mysteries from the most high God”), not by tasting or eating from the honeycomb but by finding it in her storeroom. Directly after, she explains the appearance of the honeycomb to her heavenly visitor (Jos. Asen. 16:14B/7Ph). By tasting from the honeycomb, the short text transforms Aseneth into a prophet who expands the nonretaliation formula “do not repay evil with evil” to one’s direct enemy (28:4Ph).[37] The longer versions of the text embellish the scene with more figurative symbols, like an expansion on the food in paradise (Jos. Asen. 16:16B), allusions to the Song of Songs (Jos. Asen. 16:19–20Ph; cf. Song 4:11; 5:1), and death and resurrection (Jos. Asen. 16:22–26). Neither the short nor the long text explains exactly when Aseneth’s transformation happens.[38] The lack of exactness is, in my view, also a result of the many reworkings of the text by its Jewish and later Christian readers.

Yet different applications of a given pattern can only be observed after the pattern is established. I am thankful to Warren for disclosing its existence. By hierophagy, not only do literary characters get a sense of the gustation of divine presence, but also this mystical experience indeed transforms its readers as well.

[1] Birgit Recki, “Taste,” in Religion Past and Present. Website: https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/religion-past-and-present/*-SIM_08539. Consulted online on 30 August 2019.

[2] Meredith J. C. Warren, Food and Transformation in Ancient Mediterranean Literature (WGRWSup 14; Atlanta: SBL Press, 2019) 1.

[3] Warren, Food, 2.

[4] Cf. Warren, Food, 3.

[5] Cf. Warren, Food, 4-9.

[6] See Richard Hunter (Cambridge) and Philip R. Hardie (Cambridge), “Literary Genre,” in Brill’s New Pauly. Website: https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/brill-s-new-pauly/*-e706400 Consulted online on 25 August 2019.

[7] Standhartinger, “Zur Wirkungsgeschichte von Joseph und Aseneth,” in Joseph und Aseneth, ed. Eckart Reinmuth (Sapere 15; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2009), 219–34.

[8] Warren, Food, 2.

[9] Cf. Fritz Graf (Columbus, OH), “Ambrosia,” Brill’s New Pauly. Website: https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/brill-s-new-pauly/*-e117560. Consulted online on 28 August 2019 . See also Wilhelm H. Roschner, Nektar und Ambrosia mit einem Anhang über die Grundbedeutung der Aphrodite und Athene (Leipzig: Teubner, 1883), 51–55.

[10] Homeric Hymn to Demeter, 231–50. See further Hesiod, Catalogue of Women frag. 20a.21 (Mos, LCL = frag. 23a21 Merkelbach); Homer, Il. 5.242; Ovid, Metam. 4.239–51 et al. For more evidence see N. J. Richardson, The Homeric Hymn to Demeter (Oxford: Clarendon, 1974), 237–38.

[11] Philo argues in Spec. 1.303 that virtues confer even more immortality than nectar.

[12] Wis 19:21. Warren, Food, 11, points also to Hist. Rech. 7:2; 11:4; 12:4; and Prot. Jas. 8:2.

[13] See Ps 77:25 (LXX); Wis 16:20.

[14] Such different texts, like 1 En. 31.1 (2nd c. BCE) and Acts Thom. 6f; 25; 36 (2nd c. CE), agree on this fact.

[15] Sib 5.281–83; Rev 2:17.

[16] Philo, Deus 155.

[17] Aristotle, Metaph. 3.4.11–13 (1000a5–18). Translation LCL.

[18] David Goodman, “Do Angels Eat?,” JJS 37 (1986), 160–75; Tobias Nicklas, “‘Food of Angels’ (Wis 16:20),” in Studies in the Book of Wisdom, ed. Géza G. Xeravits and József Zsengellér (JSJSup 142; Leiden: Brill, 2010) 83–100), 84–86.

[19] Gen 18:8; 19:3.

[20] See Judg 6:21–22; 13:1; L.A.B 42:8; Josephus, Ant. 282–84. In T. Ab. A 4, the archangel Michael states explicitly: Κύριε, πάντα τὰ ἐπουράνια πνεύματα ὑπάρχουσιν ἀσώματα, καὶ οὔτε ἐσθίουσιν οὔτε πίνουσιν (All heavenly spirits are bodiless, and they neither eat nor drink). Cf. Philo, Abr. 118 below.

[21] Josephus, Ant. 197: οἱ δὲ δόξαν αὐτῷ παρέσχον ἐσθιόντων. Cf. Philo, Abr. 118: “It is a marvel indeed that though they neither ate nor drank they gave the appearance of both eating and drinking. But that is a secondary matter; the first and greatest wonder is that, though incorporeal, they assumed human form to do kindness to the man of worth. For why was this miracle worked save to cause the Sage to perceive with clearer vision that the Father did not fail to recognize his wisdom?” (LCL; τεράστιον δὲ καὶ τὸ μὴ πίνοντας πινόντων καὶ τὸ μὴ ἐσθίοντας ἐσθιόντων παρέχειν φαντασίαν. ἀλλὰ ταυτί γε ὡς ἀκόλουθα· τὸ δὲ πρῶτον ἐκεῖνο τερατωδέστατον, ἀσωμάτους ὄντας [τοῦδε σώματος] εἰς ἰδέαν ἀνθρώπων μεμορφῶσθαι χάριτι τῇ πρὸς τὸν ἀστεῖον· τίνος γὰρ ἕνεκα ταῦτα ἐθαυματουργεῖτο ἢ τοῦ παρασχεῖν αἴσθησιν τῷ σοφῷ διὰ τρανοτέρας ὄψεως, ὅτι οὐ λέληθε τὸν πατέρα τοιοῦτος ὤν). T. Abr. A 4–5 has a humoristic account of this idea. Rabbis agree; see Pesiqta Rabbati 42 Bl 179 b; Tg. Yer. I at Gen 18:8; B. Mes 86b; Rab. Gen. 48:16. See also Warren, Food, 9–10. The same concept is used in Tob 12:19.

[22] Philo, QG 4.9 (Gen 18:8) LCL.

[23] Exod 34:28; Deut 9:9, 19.

[24] Exod 24:9–11. On this tradition, see also Andrea Lieber, “‘I Set a Table before You’: The Jewish Eschatological Character of Aseneth’s Conversion Meal,” in JSPE 14 (2004), 63–77; and Andrea Lieber, “Jewish and Christian Heavenly Meal Traditions,” in Paradise Now: Essays on Early Jewish and Christian Mysticism, ed. April D. DeConick (Leiden: Brill, 2006), 313–39.

[25] Philo, QE 2.39. Translation LCL. Rabbinical literature reflects this tradition as well. See Gen. Rab. 2.2; Lev. Rab. 20.10; and Lieber “Jewish and Christian Heavenly Meal Traditions,” 326–29.

[26] Apoc. Ab. 12:1–2.

[27] For some different ideas of Epicurus, see Kelli C. Rudolph, “Introduction: On the Tip of the Tongue: Making Sense of Ancient Taste,” in Taste and the Ancient Senses, ed. Kelli C. Rudolph (New York: Routledge; London: Taylor & Francis), 1–21, esp. 10–11.

[28] Carolyn Korsmeyer, Making Sense of Taste: Food & Philosophy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999), 11–12. Pace Warren, Food, 15–16, who notes this but argues that taste is “the most intimate of the traditional senses” anyway.

[29] See Philo, Abr. 149, 241; Spec. 4.100.

[30] Cf. Thomas Arentzen, “Struggling with Romanos’s Dagger of Taste,” in Sense Perception in Byzantium, ed. Susan Ashbrook Harvey and Margaret Mullet (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, 2017), 160–82, esp. 170. Arentzen observes that Christian influence changes the view on taste until late antiquity.

[31] See Svevo D’Onofrio, “Savouring the Ineffable: Metaphors of Taste in Mystical Experience across Religions,” in Religion für die Sinne – Religion for the Senses, ed. Philipp Reichling and Meret Strothmann (Oberhausen: ATHENA, 2016), 237–49.

[32] Karina M. Hogan, Theologies in Conflict in 4 Ezra: Wisdom Debate and Apocalyptic Solution (JSJSup 130; Leiden: Brill, 2008), 214–17. David E. Aune, “John’s Prophetic Commission and the People of the World (Rev 10:8–11),” in The Church and Its Mission in the New Testament and Early Christianity [FS Hans Kvalbein] , ed. David E. Aune and Reidar Hvalvik (WUNT 404; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2018), 211–25, esp. 215–20.

[33] See, e.g., Sir 1:16; 24:19–21. For food as a metaphor of teaching, see Seven Muir and Frederick S. Tappenden, “Edible Media: The Confluence of Food and Learning in the Ancient Mediterranean,” Lexington Theological Quarterly (Online) 47 (2017), 123–47.

[34] The paradise scene is only the end of her longer vision, in which she climbs up the golden ladder, attacked by a dragon. It is also paralleled by the vision about her brother Dionocrates, whom she is able to move to from an inhuman to a more pleasant place with a golden bowl of water to drink (Mart. Perpet. 7–8).

[35] For the history of interpretation, see Standhartinger, “Recent Scholarship on Joseph and Aseneth (1988–2013),” Currents in Biblical Research 12 (2014), 353–406. Some more recent interpreters no longer start with texts but with narrative patterns. See recently, Jill Hicks-Keeton, Arguing with Aseneth (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

[36] The other text of this tradition is 1 Cor 10:1–14, where Paul denies that the wilderness generation was transformed by heavenly food and drink because, immediately after they had been nourished, they transgress all of God’s commands.

[37] See Standhartinger, “Joseph and Aseneth: Perfect Bride or Heavenly Prophetess,” in Feminist Biblical Interpretation: A Compendium of Critical Commentary on the Books of the Bible and Related Literature, ed. Luise Schottroff and Marie-Theres Wacker (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2012), 578–85.

[38] Some manuscripts with a longer text place the transformation in the act of recognizing her bridal appearance in a water basin – that is, through their changing in chapter 18B.

Angela Standhartinger, Prof. Dr., is Professor for New Testament Studies at the Philipps-University Marburg, Germany. Her research focuses on Jewish Hellenistic Literature, Greco-Roman Meals and the Origin of the Eucharist, Gender studies, Pauline and Deutero-pauline Letter Writing. Her most recent publications include: “Performing Salvation: The Therapeutrides and Job’s Daughters in Context, in: Re-Making the World: Christianity and Categories, Essays in Honor of Karen L. King, edited by Taylor G. Petrey (WUNT 434; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2019), Pages 211–223; “Meals in Joseph and Aseneth” in: T&T Clark Handbook to Early Christian Meals in the Greco-Roman World, edited by Soham Al_Suadi and Peter-Ben Smit (London and New York: T&T Clark, 2019) Pages 211–223; “‘… und sie saß zu Füßen des Herrn‘ (Lk 10:39). Geschlechterdiskurse in antiker und frühchristlicher Mahlkultur,” in Gender and Social Norms in Ancient Israel, Early Judaism and Early Christianity: Texts and Material Culture. Edited Michaela Bauks, Katharina Galor und Judith Hartenstein (JAJ.S 28, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2019) 119–141, “Weisheitliche Idealbiografie und Ethik in Phil 3,” Novum Testamentum 61,2 (2019) 156–175; “Member of Abraham's Family? Hagar's Gender, Status, Ethnos, and Religion in Early Jewish and Christian Texts,” in: Abraham's Family. A Network of Meaning in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Edited by in Lukas Bormann (WUNT 415, Tübingen 2018) 235–259.

SBL 2019 Review Panel | Food for Thought: Eating and Drinking with Meredith J. C. Warren

Warren clearly states that she is not interested in using narratives about hierophagy as evidence to reconstruct ancient rituals; instead she focuses on how these narratives describe the effects of ritual consumption of otherworldly food or drink within narrative worlds.

Read MoreSBL 2019 Review Panel | Much Depends on Dinner

Meredith Warren’s new monograph invites us to revisit some well-read ancient texts with new questions about particular narrative details—specifically, to ask: what is happening when characters in these texts ingest food from another realm?

Read MoreSBL 2019 Review Panel | Food and Transformation

The papers published here were originally presented at the 2019 SBL Annual Meeting in San Diego, California at a review panel of Meredith J. C. Warren’s recent book, Food and Transformation in Ancient Mediterranean Literature (WGRWSup 14; Atlanta: SBL Press, 2019).

Read MoreAffecting Corinth

My dissertation focuses on the role of thinking, feeling, and remembering in the relations between Paul and the Corinthians to demonstrate how social worlds, boundaries, and power structures are (re)produced. I argue that attention to affect prompts a rethinking of the production (or dissolution) of Pauline authority and the concomitant making (or unmaking) of social relationships in the Corinthian assembly.

Read MoreIntroduction to the Masorah | The Masorah of the Cairo Codex of the Prophets in Perez-Castro's Printed Edition

The Masorah of the Cairo Codex of the Prophets in Perez-Castro’s Printed Edition[1]

The following article examines the methods and conventions utilized by F. Perez-Castro's editorial team, who have produced the eight-volume series El Codice de Profetas de el Cairo, which transcribes the contents of the Cairo Codex. This critical series represents more than a decade's worth of work painstakingly presenting the contents of the Cairo Codex in a format that is accessible and which meticulously follows the original manuscript. Beyond transcribing the Hebrew text of the Prophets, the series preserves the Masorah notes and offers editorial footnotes discussing this marginalia when the note is of scholarly concern. To accomplish this task and to shed light on the importance of its preservation through a printed edition, a look at the history and dating of the original manuscript would be beneficial.

Disappearing from direct scholarly access in 1984[2], the Cairo Codex was once believed to be the oldest vocalized manuscript of the Nevi’im to be extant in the 20th Century. The manuscript itself contained nearly 600 pages of text written on gazelle-hide parchment measuring 16 inches long by 15 inches tall. Also included in the manuscript were 14 carpet pages decorated in geometric patterns of small Hebrew text as well as colored inks and gold leaf. The claim for its antiquity begins in the first colophon of the manuscript itself. The author of the colophon claims the text of the manuscript was completed by 896 CE and attributes its authorship to Moshe ben Asher. This dating would indeed make it the oldest extant manuscript of the Hebrew Scriptures. Unfortunately, the colophon’s authenticity is questioned by some.[3]

Much of the early investigation into the authenticity of the Cairo Codex did support the early dating of the manuscript. In one of the first facsimiles made of the manuscript, published in 1971, D.S. Löwinger posits[4] a dating 895-897. Even at this early stage of the investigation, Löwinger notes there were doubts about the authenticity of at least the authorship of Moshe ben Asher.[5] Despite these doubts, scholars as late as the closing of the 20th Century[6], with some prefacing[7], were still espousing the early dating of the manuscript.[8]

Other studies of the writing style of the colophon seemed to support its authenticity,[9] but just as Löwinger predicted in his introduction to the first facsimile of the Cairo Codex in 1971 when he said, “… this problem will ultimately be solved by radioactive analysis,”[10] the debate continued until radio-carbon dating could be performed on the manuscript. The results of the testing place the date of the manuscript at around 990CE.[11] Further scholarship supported this later date, and the colophon was declared a forgery. It was accepted as such by a majority of scholars and remains so today.[12]

Whichever dating the reader finds most persuasive, the importance of the manuscript as one of the earlier copies of the Nevi’im with its robust Masoretic notes is evident. To scholarship’s great benefit, a printed edition was created before the original manuscript was lost in 1984.[13] As noted in the preface to the series,[14] the goal of the Perez-Castro team was not to create a comparative volume that analyzed the differences between the other early manuscripts. Instead, it was to present the text of Cairo on its own in a faithful rendition.

The editorial team first began publishing this series in 1979 with the volume VII, Profetas Menores, as well as the aforementioned Prefacio. The series then published volume I, Josue – Jueces (1980); volume II, Samuel (1983); volume III, Reyes (1984); volume IV, Isaias (1986); volume V, Jeremias (1987); volume VI, Ezequiel (1988); and finally volume VIII, Indice Alfabetico de sus Masoras (1992). These volumes provide a series of tools to help the reader in the study of text and Mesorah. A crucial part of each introduction in the volumes is the Abreviaturas y Siglas Utilizadas en las Masoras. This simple list provides a quick reference to nearly all of the Masoretic abbreviations used within the volume.

Figure 1[15]

As these abbreviations are often common between manuscripts, this list is not only useful for deciphering the Masoretic notes of Cairo but would also aid in the study of other manuscripts and their Masorah.

The main body of each volume is comprised of a transcription of the consonantal Hebrew text typed onto the page. In a show of fantastic dedication, the vowel pointing on the Hebrew text was later added by hand. The text itself does not precisely follow the placement found in the manuscript. The original often renders the Hebrew in three columns oriented in the standard right to left justification. When reading the text, one may notice a series of mem-im (מ). These indicators are used as space fillers to indicate that the manuscript did not have a space at this position. This system is needed because, at other points in the recreation of the text, the editorial team renders the Hebrew text in the same way it is presented in the original manuscript.

Figure 2[16]

Figure 3[17]

Underneath the text itself are two apparatuses. One is a rendering of the Masorah parva notes as well as the Masorah magna lists, and the other is a listing of clarifications, footnotes, or additional explanatory notes. The Masorah notes found within the first apparatus collate the Masorah parva notes found in the margins of the original manuscript into a list ordered by the appearance of the noted word within the Hebrew text. If the observed word also has an associated Masorah magna note, it is rendered in the same position on the list.

Perez-Castro utilizes a few techniques to organize the list of Masoretic notes in a way that makes it easy to follow and to quickly reference when studying the text. The note is broken up into verses, and the verse numbers are printed at the beginning of each list. If the list contains multiple verses, a double bar line ( || ) is utilized to divide the list, after which the new verse number is indicated. Within a note, reading right-to-left, the full vowel pointed, and cantalized word in question is reprinted, followed by a left square bracket ( [ ). If the note is a Masorah parva note, the letters "MP" are used to indicate this, and the actual Masorah parva note is printed. Notes within the same verse are divided by a single bar line ( | ). If the note is a Masorah magna note, the letters "MM" are used to indicate this, and the catchwords[18] are rendered in their original order. The editorial team helpfully resolves the catchwords to the biblical references and places them in parenthesis after the words. The letters "MP" follow the Masorah magna list if the associated word also has a Masorah parva note on the same page of the manuscript.

Figure 4[19]

In some cases, the word in which the original manuscript marks having Masoretic interest does not have an associated Masoretic note. Instead, it is merely listed as part of a specialized list pointing out unique aspects. One particularly tricky example is that of the word לַשָּׁרוֹן found in Joshua 12:18. The Hebrew text itself is rendered in a stylized word alignment with the Masoretic list in question being located in a large gap between words within the verses. The style of the text is rendered faithfully within the body of the printed edition, but the interstitial Masoretic list is brought down to the first apparatus. Here the editorial team indicates the lack of an actual Masoretic note by using an empty set of curly braces ( { } ). Though there is no indication that this is the purpose of the list, it becomes clear from merely looking at the words highlighted that it is a list of words that end with a vav and a final nun (ון). The apparatus does not recreate the stylistic way in which the list is rendered within the text. It merely reproduces the catchwords along with their biblical references and then the highlighted word at the end.

Figure 5[20]

Volume VIII[21], the last in the series and the last to be published, acts as an extended index of the Masorah magna and Masorah parva found in the Cairo Codex and rendered in alphabetical order. This one, of all the volumes, offers the most value to scholars of Masoretic notes as it provides a wonderfully quick way to access every note within the collected volumes. The index is arranged by grouping the words alphabetically by their roots. Then, within the root groupings, words are listed according to their forms, as found in the biblical text. Each entry provides not only the biblical reference but also an indication of being either (or both) a Masorah magna (MM) or a Masorah parva (MP) note. For those interested in knowing the location of each note from a long list of MP notes, this index provides a time-saving reference for which further study is made all the easier. If a Masoretic note references a phrase, the editors have helpfully provided a cross-reference system pointing the user back to the main entry found under the first one in the phrase.

While volume VIII was the final volume in the series lead by Perez-Castro, the editorial team, namely Emilia Fernandez Tejero and Maria Teresa Ortega Monasterio, went on to publish two further volumes. These works separate the Masorah magna[22] and Masorah parva[23] into two distinct books. As the titles would indicate, they list the various Masorah notes into a quick and easy reference volume when dealing with the Masorah notes found within the Cairo Codex. The extended works go beyond the notes listed in the Perez-Castro volumes and include the notes not directly associated with words highlighted in the original manuscript. This includes lists put into the margins of the manuscript formed into geometric shapes.[24]

Figure 6[25]

Figure 7[26]

Overall, this series is a monumental contribution to scholarship, which cannot be overstated. The care and detail which this series places on the recreation manuscript text is unparalleled, and with the loss of the actual manuscript, the work is made even more critical. This volume series is one of the last works created by scholars who have seen the actual physical manuscript able to provide a detailed recreation of the text even in places where the extant facsimile copy remains illegible. The only problem with the volume series is its lack of popularity among library staff.[27] Hopefully, as more scholars pick up the mantle of Masoretic studies, a resurgence of interest in these excellent volumes will yield a second printing.

[1] The following article does not reflect a word-for-word recording of the work presented at the SBL Annual Meeting. The talk itself was done extemporaneously with the help of presentation slides. The outline of the talk follows the basic flow of this article. Where appropriate, excerpts from the presentation slides are included here as figures.

[2] The whereabouts of the Codex is under some dispute and no solid evidence exists as to its current location. Speculation has narrowed down the location of the text to either Egypt or Israel with the individual or organization in possession of it keeping it out of public view. Nadine Epstein, “The Mystery of the Cairo Codex: on the Trail of an Ancient Manuscript,” Moment, January 2016, Accessed April 3rd, 2017. https://www.thefreelibrary.com/-a0442453992

[3] It should be noted that at the SBL 2019 Annual Meeting a vigorous discussion ensued after the presentation on the dating of the manuscript. It was made clear that total consensus has not been reached within scholarship.

[4] D.S. Löwinger, ed., Codex Cairo of the Bible. From the Karaite Synagoge at Abbasiya. The Earliest Extant Hebrew Manuscript Written in 895 by Moshe Ben Asher. A limited facsimile edition of 160 copies. 2 vols. (Jerusalem: Makor Publishing LTD, 1971), 1. In both the Hebrew and English summary introduction, Löwinger cites other scholars and dates proposed at the time. The primary citation he makes in from R Gottheil in Some Hebrew Manuscripts in Cairo. (JQR, 1905), 640, Ms. 34.

[5] Ibid., 8-10.

[6] Martin Jan Mulder, “The Transmission of the Biblical Text,” in Mikra: Text, Translation, Reading, and Interpretation of the Hebrew Bible in Ancient Judaism and Early Christianity, ed. Martin Jan Mulder and Harry Sysling (Peabody, Mass.: Baker Academic, 2004), 115. This essay was originally published in 1988 by Van Gorcum publishers in Assen, Netherlands as part of a series Compendia rerum judaicarum ad Novum Testamentum. Section 2, The Literature of the Jewish people in the period of the second temple and the Talmud.

[7] E. J. Revell, “The Codex as a Representative of the Maoretic Text,” in The Leningrad Codex: A Facsimile Edition, ed. Astrid Beck, David Freedman, James Sanders. (New York: Brill Academic Publishers, 1998), xxxi. Here Revell claims that the 896 CE dating found in the colophon is in reference to the consonantal text whereas the nekudot was added later in the style of ben-Naftali as recorded in Kitāb al-Khilaf.

[8] Israel Yeivin, Introduction to the Tiberian Masorah, trans./ed. E. J. Revell in Masoretic Studies 5 (Missoula: Scholars Press, 1980), 21.

[9] Paul Kahle, The Cairo Geniza. Schweich Lectures, 1941. (London: Oxford University Press, 1947), 97. Kahle suggests that the language of the colophon appears to be a traditionally written Karaite styled manuscript.

[10] Löwinger, ibid., 10.

[11] Malachi Beit-Arié; Mordechai Glatzer; Colette Sirat, Codices Hebraicis litteris exarati quo tempore scripti fuerint exhibentes, Monumenta paleographica medii aevi. Series hebraica. (Turnhout: Brepols, 1997), 28.

[12] דוד לייאנס, המסורה המצרפת : דרכיה וסוגיה : על פי כתב־יד קהיר של הנביאים [David Lyons, The Cumulative Masora: Text, Form and Transmission with a Fascimile Critical Edition of the Cumulative Masora in the Cairo Prophets Codex]. (Be’er-Sheva’: University Ben-Guryon ba-Negev, 2000), vii, 4-5.

[13] Nadine Epstein, ibid.

[14] F. Perez-Castro, et. al., El Codice de Profetas de el Cairo Prefacio, Textos y Estudios “Cardenal Cisneros” de la Biblia Poliglota Matritense, (Madrid: Instituto “Arias Montano”. CSIC, 1979), 22.

[15] F. Perez-Castro, et. al., El Codice de Profetas de el Cairo Profetas Menores, Textos y Estudios “Cardenal Cisneros” de la Biblia Poliglota Matritense, (Madrid: Instituto “Arias Montano”. CSIC, 1979), front matter.

[16] Cairo Codex, Judges 5:16-19

[17] F. Perez-Castro, et. al., El Codice de Profetas de el Cairo Josue – Jueces, Textos y Estudios “Cardenal Cisneros” de la Biblia Poliglota Matritense, (Madrid: Instituto “Arias Montano”. CSIC, 1980), 147.

[18] During the Masorah sessions at the SBL Annual Meeting 2019, a running discussion was had during the question and answer portions as to what scholarship should call these words and phrases. Terms such as `catchword`, `siman`, `simanim`, `general indicators` and others have been offered. I choose here to use the term catchword and the purpose of the recorded words in the manuscript are to point do different biblical references using common words or phrases found in those verses.

[19] F. Perez-Castro, et. al., El Codice de Profetas de el Cairo Josue – Jueces, Textos y Estudios “Cardenal Cisneros” de la Biblia Poliglota Matritense, (Madrid: Instituto “Arias Montano”. CSIC, 1980), 73.

[20] F. Perez-Castro, et. al., El Codice de Profetas de el Cairo Josue – Jueces, Textos y Estudios “Cardenal Cisneros” de la Biblia Poliglota Matritense, (Madrid: Instituto “Arias Montano”. CSIC, 1980), 72.

[21] F. Perez-Castro, et. al., El Codice de Profetas de el Cairo Indice Alfabetico de sus Masoras, Instituto de Filologia del CSIC, (Madrid: Departmento de Filologia Biblica y de Oriente Antiguo, 1992).

[22] Emilia Fernandez Tejero, La Masora Magna del Codice de Profetas de el Cairo: Transcripcion alfabetico-analitica, Instituto de Filologia del CSIC, (Madrid: Departmento de Filologia Biblica y de Oriente Antiguo, 1995).

[23] Maria Teresa Ortega Monasterio, La Masora Parve Del Codice de Profetas de el Cairo: Casos lêṯ, Instituto de Filologia del CSIC, (Madrid: Departmento de Filologia Biblica y de Oriente Antiguo, 1995).

[24] The Cairo Codex manuscript has many ornate lists that form unique but very angular and geometric shapes.

[25] Cairo Codex, Hosea 14:5.

[26] Emilia Fernandez Tejero, La Masora Magna del Codice de Profetas de el Cairo: Transcripcion alfabetico-analitica, Instituto de Filologia del CSIC, (Madrid: Departmento de Filologia Biblica y de Oriente Antiguo, 1995).

[27] As I was preparing for this presentation and article, no single library within the New York City area and a complete set. I was lucky enough to have access to individuals that have personal copies of the volumes and able to borrow theirs in preparing the figures for the slide presentation delivered at the SBL Annual Meeting 2019.

Introduction to the Masorah | Editing the Masorah of the Manuscript BH MSS1 (Madrid, Complutensian Library)

EDITING THE MASORAH[1] OF THE MANUSCRIPT BH MSS1 (MADRID, COMPLUTENSIAN LIBRARY)

A text cannot be edited without a proper description of the manuscript that contains it. Therefore, before explaining the criteria followed in the current edition of the Masorah of the manuscript BH Mss1 (M1), I would like to introduce to you briefly this exceptional manuscript.

1. Manuscript description

The manuscript M1 consists of 340 unpaginated folios and contains the whole Hebrew Bible except for the folios which contained Exod. IX 33b- XXIV 7b.[2] It is written in a Sephardi hand and according to the note of purchase found on f. 334v (fig. 1)[3], it was bought by R. Yishaq and R. Abraham, both doctors, in the year five thousand and forty of the creation of the world, 1280, in Toledo.

This manuscript is also known to be the one used extensively as a basis for the Hebrew text of the Complutensian Polyglot Bible edited by Ximenez de Cisneros in the 16th century (1514).

Each folio has three columns and each full column has 32 lines (fig. 2), except for the poetical portions of the Pentateuch (Exod. 15:1-19; Deut. 32:1-43; fig. 3), Judges (5:1-31), and Samuel, which are written in specially prescribed lines, as well as the poetical books (Psalms, Job and Proverbs), which are distinguished by an hemistichal division.

The text is provided with vowels and the accents. Most of the fifty four pericopes into which the Pentateuch is divided and the triennial pericopes, or sedarim, are respectively indicated in the margin by the word פרש and the letter samech, and are sometimes enclosed in an illuminated parallelogram. The division of the text into open and closed sections is exhibited by the prescribed vacant lines, indented lines and spaces in the middle of the lines.

The Masorah parva (Mp) annotations occupy the outer margins and the margins between the columns. The Masora Magna (Mm) annotations are given in three lines in the upper margin and in four lines in the lower margin of each folio. The manuscript has a huge number of Masoretic annotations in figured patterns. These annotations have been located in the Mp, the Mm and the sekum, –a short summary with general information that was usually placed at the end of each biblical book. The forms of the figured Masorah are mainly simple geometric shapes, such as triangles, semicircles, zigzags, circles or a combination. Vegetal motifs and, exceptionally, other forms (e.g., a six-pointed star, a house shape, etc.) also appear.

The thirty-seven cases of the big outer lower Mm are an exception in the context of the manuscript. Their designs, elaboration and complexity contrast with the simplicity of the other types (see outer margins fig. 2 and 3).[4]

Besides the Mp and Mm annotations, a number of lengthy Masoretic rubrics are given at the end of the Pentateuch (appendix I), Latter Prophets (appendix III) and Chronicles (appendix IV).[5] They are written in three columns of 32 lines each (fig. 4), as the folios containing biblical text.

Appendix I contains a) the Summaries to each of the fifty-four pericopes giving the sedarim, pesaqim, the number of words, letters, the variations (hillufim) between the Easterns and Westerns, the ketiv-qere and the chronology of the parasha, and b) the summaries to each of the five books of the Pentateuch giving the total occurrences of the information contained in the pericopes.

The so-called appendix III contains seventeen rubrics considered by some scholars as part of the Dikduke ha-Teamim.

Appendix IV is composed of three parts very different from each other when taking into account the contents. The first part is the repetition of the end of Appendix III and the continuation of the unfinished list. The second part is formed by three lists with midrashic explanations. The third part collects lists of Sefer Oklah we-Oklah type.

2. The current edition

The edition of the marginal annotations of one text is a long and painstaking work. Due to the way that those annotations work and how they are normally expressed, much labor must be done prior to the realization of the edition. The analysis of the marginal annotations has been done following these five steps: 1. Find the words with a circellus in the folio and the Mp annotation attached to each word; 2. Locate the Mm annotations and the words to which they are attached; 3. Identify the simanîm or catchwords; 4. Confirm if the information given in the annotations is true; 5. Understand the annotations.

In order to fulfill step 4, the marginal annotations of the principal Tiberian biblical manuscripts (Cairo Codex of the Prophets, Or 4445, Aleppo codex, and Leningrad codex) and the major Masoretic lists and treatises[6] have been consulted to check whether they contain any information similar to the annotation.

2.1. Editorial criteria

The major innovation of this edition is that only the Masorah and not the biblical text with which it appears in the manuscript is edited. The team in charge of the edition made this decision arguing that the attested differences between the various Masoretic annotations and the biblical text with which they appear proved that the Masorah is important enough to stand on its own and be edited by itself.[7]

Another important decision made by the editorial team is to transcribe the marginal annotations without any alteration or emendation, resulting in a faithful reproduction of the manuscript. So, when the catchwords are not written exactly the same that the biblical text in the manuscript, they are reproduced as they appear followed by the word sic. The defective and plene spellings have not been taken into account unless they have a direct effect on the Masoretic information.

Those Masoretic annotations which are unclear or impossible to read completely by break or wear of the manuscript are in square brackets in the edited text. The complete information according to one of the main biblical manuscripts and traditional Masoretic compilations is given in one note.

If one Masoretic annotation contains some incorrect information, it is indicated in the explanatory notes. When the information given in one Masoretic annotation does not have a parallel in any other source, this lack is registered in the corresponding explanatory notes.

2.2. Description of the edition

2.2.1. Edition of the marginal annotations

Six volumes containing the marginal annotations from the five books of the Pentateuch and the book of Joshua have been published so far.[8]

Each volume consists of an introduction, transcription and study of the marginal annotations, and two indexes.

The corpus is arranged in entries, each separated by three asterisks.

Each entry may consist of: 1) lemma (to the right) and the chapter and verse number (to the left), 2) the transcription of the Mp and Mm annotations with the identification of the simanim or catchwords when they are given, and 3) the explanatory notes.

1) The lemma refers to each word or group of words in the text which carries a Masoretic annotation, and which is, in nearly every case, marked by a circellus, i.e., a graphic symbol – a small circle – often placed over one word or between two or more words of the biblical text.

In absence of the circellus, this is mentioned in the explanatory notes.

The lemma is reproduced as it appears in the biblical text of the manuscript but without vowels signs and accentuation. Vowel signs have only been used to differentiate similar consonantal spellings which could lead into error. The lemma is provided with accentuation in cases where the annotation is concerned with accented words.

2) This is followed by the transcription of the Masoretic annotations.

On the right-hand side is an indication that the annotation is either Mp or Mm. This indication is followed by the Masoretic annotation as it appears in the manuscript.

The identification of the catchwords, both Hebrew and Aramaic, are given in parentheses. Letters in superscript (Mm and Mp) show whether the word has a Masoretic annotation elsewhere in the manuscript.

The liturgical sections which are marked with the letters, samek, peh or the word parasha in the manuscript are also indicated.

3) The explanatory notes placed at the end of each entry are one of the most helpful tools of this edition. They cover various things: information relative to how the text appears in the manuscript (different hands, lack of the circellus, etc.); information resulting from the process of studying and editing each annotation (if one siman has been repeated or omitted, when an annotation is incomplete, when the information is incorrect, the parallel occurrences in other manuscripts and Masoretic works, etc.); any other necessary information to fully understand each annotation.

Each volume has two indexes at its end: the first one of lemmas in alphabetic order with the exceptions of particles and pronouns; the proper names are listed in the second part of this index. The second index presents a table with the Biblical quotations referred to in the Masoretic annotations of that book.

2.2.3. Edition of the Masoretic Rubrics

For the first time, this kind of Masoretic material has been edited and studied.[9]

The norms followed in the edition of these appendices are, in general, similar to those described for the volumes on the marginal annotations. The corpus is arranged in entries, but because of their varied form and content, the edition of each appendix has its own peculiarities and layout to facilitate its comprehension and consultation.

Appendix I

The text is arranged in three columns: the lemma of the information (sedarim, parasiyot, etc) followed by the corresponding number, when it appears in shortened form, is placed in the first column. But if the number is not given in shortened form, it is placed in the second column. The simanim are placed in the second column. And their identification appears in the third column.

The parasiyot are referred to in the manuscript by the mnemonic siman instead of by their names. In the edition, the name of the parasha and the verses it comprises have been added into square brackets.

Appendix III

The text of this appendix continues apart from the simanim and their identification which are arranged in two columns.

The comparison of the content of this appendix with the most significant sources has shown that the text of M1 is original in its final form, with elements of the four sources consulted as well as others of its own. Thus, to appreciate better these differences and similarities, the complete text of the sources is offered in an attachment placed immediately after the appendix.

Both texts, the appendix and the attachment, appear underlined: a) the text of the appendix when it is not corroborated by any source, and b) the text of the sources when it is not similar to the M1’s text. A number in square brackets is placed at the beginning of each list in the text of the appendix. In the attachment, the sources used to check each list have the same number.

Appendix IV

The three parts that form up this appendix have each own layout.

For the first part, which is the repetition of the end of Appendix III and the continuation of the unfinished list, the layout for Appendix III is followed: the text is continuous, apart from the simanim and their identification which are arranged in two columns.

For the second part, that is the three lists with midrashic explanations, the heading is separated from the rest of the text.

For the third part, with lists of the Sefer Oklah we-Oklah type, the heading is separated from the information which is arranged in three columns. The first column has the word which relates to the information or, in some cases, one word representative of the siman. The simanim are placed in the second column and their identification in the third one.

The translation of the headings into Spanish is given in square brackets at the beginning of each list.

The words related to the phenomenon ketiv-qere are usually written in the manuscript according to the ketiv. If those words are written according to the qere this is registered in the corresponding explanatory note.

Two indexes are placed at the end of this volume: the first one of lemmas and the second one with the biblical quotations. The index of lemmas is formed by three different lists, one to each appendix. In the index of Appendix I the names of the parasiyot and the summary of the books of the Pentateuch are pointed out. In the two other indexes the headings of the lists are pointed out, arranged in alphabetical order.

Dr. Elvira Martín-Contreras is Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Mediterranean and Near Eastern Languages (CSIC).

[1] The technical term refers to the annotations that appear next to the consonant text of the Hebrew Bible in the margins of the so-called Masoretic codices. See A. Dotan, “Masorah”. In Encyclopaedia Judaica. Second Edition, vol. XIII, 614.

[2] Digitized version: http://dioscorides.ucm.es/proyecto_digitalizacion/index.php?doc=5309439296&y=2011&p=1

[3] All the images of the article belong to BH Mss1 at the Biblioteca Histórica Marqués de Valdecilla. Reproduced with the permission of the Biblioteca Histórica Marqués de Valdecilla.

[4] E. Martín-Contreras, “The Image at the Service of the Text: Figured Masorah in the Biblical Hebrew Manuscript BH Mss1” Sefarad 76 (2016) 55-74.

[5] For a complete description of these material cf. E. Martín Contreras, “M1’s Masoretic Appendices: A New Description,” JNSL 32 (2006), 65-81.

[6] F. Díaz Esteban, Sefer Oklah we Oklah (Madrid: CSIC, 1975); A. Dotan, The Diqduqé hatteamim of Aharon ben Moshe ben Asher, with a Critical Edition of the Original Text from New Manuscripts (Jerusalem, 1967); S. Frensdorff, Das Buch Ochlah W’Ochlah (Hannover, 1864); C. D. Ginsburg, The Massorah Compiled from Manuscripts Alphabetically and Lexically Arranged, With an Analytical Table of Contents and Lists of Identified Sources and Parallels by A. Dotan, 4 vols. (New York: Ktav, 1975); B. Ognibeni, La seconda parte del Sefer Oklah weOklah (Madrid: CSIC; Fribourg: University of Fribourg, 1995).

[7] A. Dotan, “The Contribution of the Modern Spanish School to Masoretic Studies,” Estudios Bíblicos LXVIII (2010), 411-418: 416.

[8] E. Fernández Tejero, Las masoras del libro de Génesis. Códice M1 de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid (Madrid: CSIC, 2004); M.ª T. Ortega Monasterio, Las masoras del libro de Éxodo. Códice M1 de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid (Madrid: CSIC, 2002); M.ª J. Azcárraga Servert, Las masoras del libro de Levítico. Códice M1 de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid (Madrid: CSIC, 2004); M.ª J. Azcárraga Servert, Las masoras del libro de Números. Códice M1 de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid (Madrid: CSIC, 2001); G. Seijas de los Ríos, Las masoras del libro de Deuteronomio. Códice M1 de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid (Madrid: CSIC, 2002); E. Fernández Tejero, Las masoras del libro de Josué. Códice M1 de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid (Madrid: CSIC, 2009).

[9] E. Martín-Contreras, Apéndices Masoréticos. Códice M1 de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid (Textos y Estudios “Cardenal Cisneros,” 72; Madrid: CSIC, 2004)

Introduction to the Masorah | The Masorah of the Leningrad Codex in the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS) Edition

Ancient Jew Review is pleased to host this panel, first presented at SBL 2019 in San Diego as “ A Beginner's Guide to the Masorahs of Four Great Early Manuscripts as Represented in Recent Printed Editions.”

The Masorah of the Leningrad Codex in the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS) Edition

The objective of this article is to give an overview of how the Masorah of BHS works. I will assume that the reader is generally familiar with the Masorah. For example, in the sample from BHS below, there is one Masoretic note on the third line. The word יִדְאֶ֖ה has a circule over it. That tells the reader it should be matched with a Masoretic note. In this case, it is the note ב̇ , “occurs two times.”

For a full treatment of how the mechanics of the Masorah works, see Kelley, Mynatt and Crawford, 46-69.

Image 1 below is the first page of text in the Leningrad Codex: Genesis 1:1-26. The Leningrad Codex is the basis for BHS, and thus its Masorah is the starting point of the Masorah of BHS. The Leningrad Codex is the oldest complete manuscript of the Hebrew Bible, dating from around 1008. Its colophon claims that the manuscript was copied from exemplars that were written by the esteemed Masorete Aaron ben Asher. For more information on the Leningrad Codex, see Wurthwein, 36-7.

Masorah Parva (Mp) notes generally count word or phrase occurrences. These notes are the brief markings that are in the side margins of the columns. In Image 2, several examples of Mp notes are circled in red. These notes are in Aramaic shorthand or abbreviations. For example, the Mp noteלׄ means that the word occurs only one time; it is unique. The note ד̇ means that the word occurs four times. The note may give additional information, such as how it is spelled, whether the word occurs at the beginning of a verse, or occurs primarily in a specific book of the Bible. For a glossary of Masoretic terms, with examples, see Kelley, Mynatt and Crawford, 69-193.

The Masorah Magna notes generally give the location of the occurrences by citing “snippets” from the verses where they occur. We are accustomed to chapter and verse citations, like “Jeremiah 13:2.” The Masoretes lived in the days before concordances and chapter/verse divisions. They identified specific verses by giving short quotations from the verses. Thus, the Mm notes give these short verse “snippets” for each verse, identifying for the reader the location of each verse. These notes are naturally lengthier, and they are in the upper and lower margins. Image 3 shows an example. The fact that a reader could identify the location of a verse by a short quotation from it demonstrates a familiarity with the Hebrew text that surpasses most of us today who rely on concordances.

Image 4 gives approximately the same section in BHS that is represented in Image 1 for the Leningrad Codex. Notice that BHS is set up in roughly the same way, with the Mp notes along the side margins. We will return to the Mm notes below.

BHS made two big innovations, when compared to previous editions of the Hebrew Bible with the Masorah.

Innovation #1: BHS “Completed” the Masorah Parva Notes

Although there should be a Mp note for each occurrence of a text feature, that rarely happens. Typically, the Mp notes appear with only a few of the occurrences. The editor of the Masorah of BHS (Gerard E. Weil) “completed” the Mp notes so that a note is matched with each occurrence.

For example, the Mp of עִמְּךָ֖ in Genesis 26:3 is י̇ב̇ בתו̇ר (occurs twelve times in the Torah). One would expect that this Mp note would occur with each of the twelve occurrences. In fact, the note actually occurs with only four of the twelve references in the Leningrad: Gen. 21:22, 26:3, Deut. 20:20, 22:2. In the Masorah of BHS, all 12 of the occurrences will have the Mp note because the editor “completed” all of the references.

The same word or text feature can be the subject of more than one Mp note. Thus, one might wonder what would happen if one word was an occurrence in two or more Masoretic rubrics. In other words, if Weil “completed” every Mp note in the Leningrad Codex, and if words might be the subject of more than one note, then how did he put two or more Mp notes on the same word?

The answer is that Weil had to edit multiple notes into one cohesive note. Sometimes, the results are a bit messy. For example, in the Leningrad Codex in Genesis 49:11, the note for the word עִירֹה is “The Qere is עִירוֺ.” See Image 5.

In BHS, this simple note has been combined with another so that it looks much more complicated. See image 6.

The note now says: “The Qere is עִירוֺ̇. This is one of 16 occurrences written ה in the Torah, and it is unique in this form.” The combination of “completed” Mp notes produces some complicated and occasionally awkward marginal notations.

Innovation #2: The Masorah Magna Notes Are in a Separate Volume

Recall that in the Leningrad Codex, the Masorah Magna (Mm) notes are in the top and bottom margins. See Image 7 for some examples in the codex.

In BHS, all of the Mm notes have been exported to another book. This is best illustrated by way of an example. In Deut. 28:55, the word יֹאכֵ֔ל, has the Mp note 53 י̇ג̇ (occurs 13 times). See Image 8.

The superscript number 53 tells you to look for a note in the Masorah apparatus at the bottom of the page. See Image 9.

The note in the Masoretic Apparatus tells you to go find the entry for Mm 784 in this book: Weil, Gerard E. Massorah Gedolah. Vol. 1. Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 1971. This volume contains all of the Mm lists in the Leningrad Codex. Instead of printing them in BHS, they were all exported to this supplementary volume. See Image 10.

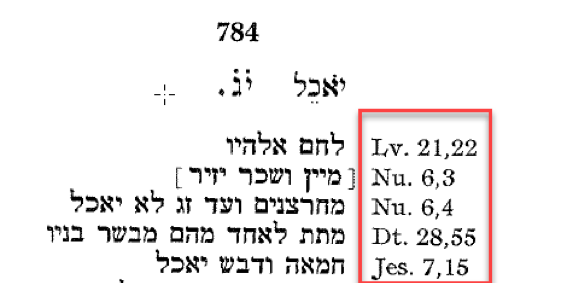

Inside this book, you will look for list 784, which happens to be on page 95. Image 11 shows you what page 95 looks like.

Image 12 is a close-up of only list 784. It gives the location of the 13 occurrences.

These lists are also heavily edited. Image 13 shows what this Mm list looks like in the Leningrad Codex. The area in highlight is the actual note and the snippets for the individual occurrences.

The changes in Massorah Gedolah are not simply a matter of putting the Hebrew into a nice typeface. Weil has added a number of editorial changes to make the book easier to use for the reader. For example, the book abbreviations and the chapter/verse locations are now included. See Image 14.

Additionally, Weil made emendations, like adding a missing snippet. In this list in the Leningrad Codex, the snippet for Number 6:3 is absent (the brackets indicate this for the reader). Weil added it so that the occurrences can be complete. See Image 15.

The Masorah of BHS has plenty of other quirky notations that are nowhere to be found in the Leningrad Codex, for example, notes marked “sub loco” or “contra textum” in the Masoretic apparatus. These relatively rare notations should not distract a new user from learning how to use the Masorah of BHS. Kelley, Mynatt and Crawford, 54-57, discusses these and other unusual notations.

Works Cited

Kelley, Page H, Daniel S. Mynatt and Timoghty G. Crawford. Masorah of Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm B. Eerdmans, 1998.

Weil, Gerard E. Massorah Gedolah. Vol. 1. Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 1971.

Wurthwein, Ernst. The Text of the Old Testament. 2d ed. Translated by Erroll Rhodes. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1995.

Daniel Mynatt is the Vice Provost for Institutional Effectiveness at the University of Mary-Hardin Baylor.

![An etching of the Serbian Orthodox Monastery of Studenica from Moscow (1758), currently housed in the Museum of the Serbian Church in Szentendre, Hungary. [Source: Wikimedia]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5449167fe4b078c86b41f810/1604953554651-NSZ4FGB324T7XQHJSZN9/1024px-Unknown_etching_moscow_1758_The_Serbian_Monastery_of_Studenica_IMG_0484_serb_museum_szentendre.JPG)

![Marco Zoppo, Saint Peter (ca. 1468) [Wikimedia].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5449167fe4b078c86b41f810/1606156007002-3TGB2TL6O1MYEYY020WX/image-asset.jpeg)

![Illuminated Armenian manuscript showing canon table (15th c.) [Source: MET Museum].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5449167fe4b078c86b41f810/1605711852169-R4SWAXGGVVGAECKFVKVG/DP342091.jpg)

![Santa Maria Maggiore (Rome) [Image courtesy of the author].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5449167fe4b078c86b41f810/1605114814811-FYC8CSIY67255WH4WHQ8/Picture1.png)

![Panagios Taphos 22. Menaion Oct. 11th cent. 301 f. Pg. 51 ft. 11th Cent, 1000. Manuscript/Mixed Material. [Source]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5449167fe4b078c86b41f810/1605112090166-XTBK3KRCIGTZ9P20Z941/image-asset.png)

![CBL W 139, Beginning of Matthew’s gospel [Image courtesy of the author].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5449167fe4b078c86b41f810/1604941023190-XAY8BK0VKJL78I5G9LMZ/DCU+Garrick+Allen+SELECTS_060+copy.jpg)

![The Hospitality of Abraham, Ravenna [Image courtesy of Flickr]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5449167fe4b078c86b41f810/1585841437225-OSE8TGGO7IKT4CPZCGKR/9333791444_5c24da9fac_c.jpg)

![Isidore Verheyden, Afternoon Tea (1905) [Wikimedia]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5449167fe4b078c86b41f810/1602457153568-ZIAORQ6C4GBGP7IODVO0/Afternoon_Tea_Isidore_Verheyden.jpg)

![Luis Meléndez, The Afternoon Meal (La Merienda), (ca. 1772) [MET Collection]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5449167fe4b078c86b41f810/1602220982629-17NSFLZ6SSS22ND9HXZ0/DT1570-1.jpg)

![Fresco of a feast from Pompeii housed at the Museo Archeologico Nazionale (Naples) [Wikimedia]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5449167fe4b078c86b41f810/1602077271507-XX8AHTFDOEEKT3RT2Y99/1024px-Pompeii_family_feast_painting_Naples.jpg)