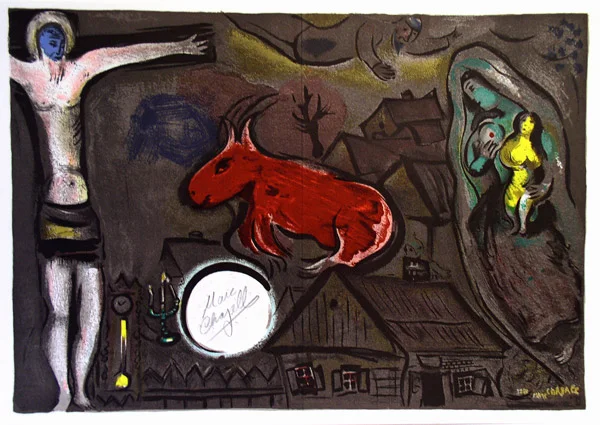

Marc Chagall's Mystical Crucifixion

It is widely accepted that the ancient rabbis fastidiously ignored the rise of Christianity and only rarely alluded to Jesus in their writings.[1]

However, as the surviving texts of the Toledot Yeshu (the Chronicles of Jesus) attests, not all Jews in antiquity avoided speculation about Jesus, his life, and the origins of Christianity.

The Toledot Yeshu, which ridicules Jesus’ birth, miracles, and death, sheds light on another Jewish response to the threat and allure of Christianity. It may surprise some to hear of Jews engaging in such negative discourse. Mockery, however, is one of the most powerful tools of the weak,[2] and it is not surprising that Jews resorted to this tactic at various times and places.

It is worth mentioning that Jews were not the first to mock Jesus’ life-story: the Greek philosopher Celsus famously derided Jesus’ origins and Christianity in the second century C.E. treatise On the True Doctrine, some details of which are paralleled in the Toledot Yeshu.

Toledot Yeshu is a decidedly non-rabbinic counter-narrative and satire of the foundational story of Christianity, which likely originated in the late antique or early medieval period.[3] It probably circulated orally for centuries before being transcribed in various places and times. A version of it was already known to the archbishop Agobard of Lyons in 827 CE, who complained of the Jews’ public and aggressive use of such vitriol to influence potential Christian converts’ attitudes towards Jesus.[4] According to some late medieval sources, it was a Jewish custom to read Toledot Yeshu on Christmas Eve.[5]

In the genre of the folk story, no two manuscripts are identical and storytellers likely embellished it with every recounting. The earliest texts survive in Aramaic fragments found in the Cairo Genizah, but retellings of this narrative survive in virtually every Jewish language. Samuel Krauss brought scholarly attention to this work in 1902 with his Das Leben Jesu nach judischen Quellen (now available in the public domain). Mohr-Siebeck has just published two volumes on the Toldedot Yeshu, with an introduction, translation, and critical edition of the work as well as access to a database of all the manuscripts.[6]

As John Gager explains, the trouble with Jesus’ origins is evident in the gospels.[7] The Gospel of Mark calls Jesus “the son of Mary” (6:3), likely betraying the fact that his father’s identity was disputed; the Gospel of Luke omits this embarrassing passage while the Gospel of Matthew gives him an honorable patrilineal lineage through Joseph (and carefully includes other controversial mothers like Tamar, Ruth, Rahab, and Bathsheba) even as it claims he was conceived by the holy spirit.

Much like the earliest gospel, that of Mark, the earliest recensions of Toledot Yeshu lack his birth narrative. These narratives focus on how Jesus acquired his miraculous powers (according to one version, he stole the name of God from the temple); how he fooled the masses with magic and false miracles; how the rabbis came to excommunicate him; how the Romans convicted him; how he died a charlatan’s death (hanging not even on a tree, but on a cabbage stalk); and suffered a criminal’s burial. As Gager notes, the texts are particularly preoccupied with finding a justification for Jesus’ death, an unsurprising concern in light of Christian accusations that Jews had killed the messiah.

Still, as Gager asserts, occasionally positive glimpses of Jesus remain in the Jewish texts. In a famous passage in the Talmud, Jesus is presented as a brilliant student, who is wrongly pushed away by Rabbi Joshua ben Perachia (cf. Sanhedrin 107b; Sotah 47a).[8] Echoes of this storyline sometimes appear in Toledot Yeshu. In these retellings, Jesus’ apostasy was not a foregone conclusion.

In the later versions of Toledot Yeshu that do contain Jesus’ birth narrative, the author(s) graphically deride every aspect of the virgin birth: Jesus’ father was a villain,[9] the conception happened by rape and adultery, and Jesus’ mother was menstruating at the time of conception (a taboo to Jews and Christians). In one version, his conception even takes place on Yom Kippur.[10] This section of the narrative is so sexually graphic that Yair Furstenberg has suggested that it served as a manual, modeling proper and forbidden sexual behavior in folkloric form.[11]

Interestingly, in almost all versions, Mary herself is portrayed as blameless, an upstanding Jewess who abides by Jewish law, and who is taken advantage of by a villain. Here, we might see evidence of Jewish attraction to a mother of the messiah figure, scattered evidence of which can be found through the medieval period.[12]

Paul too proves intriguing, alighting on the scene much like the prophet Elijah.[13] Since Jesus’ heresy provokes endless infighting among the Jews, Toldot Yeshu portrays Paul (or, in some versions, Simon-Peter) as the unwitting religion-founder and peacemaker, who separates the Christians from the Jews. Working as a double agent on behalf of the pious Jews, Paul dictates a new language to the heretics and teaches them new songs in order to definitively separate Jesus-followers from other Jews. And thus, a new religion is founded.

The Christian gospels were not the only texts that served as background for the authors of Toledot Yeshu. Sarit Kattan Gribetz has suggested that Megillat Esther is also a source for this narrative, repeatedly invoked, explicitly and implicitly, in the extant manuscripts. Just as Megillat Esther purports to depict Jews overcoming the threat of Haman in Persian times, so Toledot Yeshu shows Jews triumphing over Jesus. The allusions to Megillat Esther might even point to the performative usages of Toledot Yeshu as a form of megillah read by Jews on Christmas.[14]

Toledot Yeshu sheds light on an important aspect of Jewish-Christian relations. In this case, given narratives of Jewish powerlessness and lack of agency, Toledot Yeshu reveals some of the ways that Jews mocked, resisted, and subverted hegemonic narratives of the Christian world around them. Thus, it serves as an important corrective to the lachrymose theory of Jewish history.

Many scholars prefer to avoid discussion of Toledot Yeshu, which recalls uncomfortable periods of history when relations between Jews and Christians were antagonistic. Unfortunately, such avoidance of history has disastrous consequences. I would argue that it is the parts of our history that we refuse to look at that pose the most danger to us. Avoidance of historical shortcomings encourages complacency, displacement of responsibility, and lack of sensitivity to others. It is when we confront the difficult parts of our shared history that we can come to terms with why people needed such mockery and why others might employ such rhetoric against them, understanding the historical violence and prejudice that shaped this text. It is only when we confront that part of the human spirit that loves to degrade the other that we can invite in more enlightened responses.

In these dreary winter days, let us invite in the light, especially to the most difficult parts of our histories.

Mika Ahuvia is currently an Assistant Professor of Classical Judaism at the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies and the Jackson School of International Studies at the University of Washington

[1] Notwithstanding Peter Schäfer’s books on the topic: see his Jesus in the Talmud (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2007) and The Jewish Jesus: How Judaism and Christianity Shaped Each Other (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012).

[2] Cf. Saul Alinsky, Rules for Radicals (1971), who writes that ““Ridicule is man’s most potent weapon.” It is interesting to think on this problem with the controversy surrounding the movie The Interview and North Korea’s response.

[3] See Peter Schäfer, Michael Meerson, and Yaacov Deutsch, Toledot Yeshu ("the Life Story of Jesus") Revisited: A Princeton Conference (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2011); David Biale, “Counter-History and Jewish Polemics against Christianity: The ‘Sefer toldot yeshu’ and the ‘Sefer Zerubavel,’ Jewish Social Studies 6:1 (1999): 130-145.

[4] Schäfer, “Agobard’s and Amulo’s Toledot Yeshu” in Toledot Yeshu ("the Life Story of Jesus") Revisited.

[5] Marc Shaprio, “Torah Study on Christmas Eve,” The Journal of Jewish Thought and Philosophy 8:2 (1999): 334.

[6] See http://www.mohr.de/en/nc/theology/text-editions/buch/toledot-yeshu-the-life-story-of-jesus.html

[7] John Gager and Mika Ahuvia, “Some Notes on Jesus and his Parents: From the New Testament Gospels to the Toledot Yeshu,” Envisioning Judaism: Studies in Honor of Peter Schäfer on the Occasion of his Seventieth Birthday (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2013).

[8] Gager and Ahuvia, “Some Notes on Jesus and his Parents,” and Schäfer, Jesus in The Talmud, 34-40.

[9] An interesting parallel between Celsus’ version and the Jewish sources is that the villain is named Pandera; however, in the Toldot Yeshu he is not a soldier, but often described as an attractive, lowborn and promiscuous man (N.B. his Jewish identity is implicit, not explicit).

[10] Huldreich (Amsterdam) ms.

[11] Suggested in the Toledot Yeshu seminar, Princeton University (2009).

[12] Gager and Ahuvia, “Some Notes on Jesus and his Parents”; Martha Himmelfarb, “The Mother of the Messiah in the Talmud Yerushalmi and Sefer Zerubbabel,” The Talmud Yerushalmi and Graeco-Roman Culture (ed. Schäfer; Vol. 3, 1998).

[13] William Horbury, “The Strasbourg text of the Toledot,” in Toledot Yeshu ("the Life Story of Jesus") Revisited.

[14] Sarit Kattan-Gribetz, “Hanged and Crucified: The Book of Esther and Toledot Yeshu,” Toledot Yeshu ("the Life Story of Jesus") Revisited.