Ronis, Sara. “Do Not Go Out Alone at Night”: Law and Demonic Discourse in the Babylonian Talmud. Ph.D. Dissertation. Yale University, 2015.

This project focuses on the modes of controlling, avoiding, and appropriating demons in the Babylonian Talmud, with particular attention to rabbinic legal discourse. Though scholars have largely overlooked demons as a source of information about rabbinic law, cross-cultural interaction, and theology, this dissertation has asked how the inclusion of rabbinic demonology enriches our picture of rabbinic discourse and thought in Late Antique Sasanian Babylonia.

I analyze rabbinic legal passages relating to demons within their larger textual, redactional, and cultural – Zoroastrian, Christian, and ancient Near Eastern – contexts, in order to uncover and highlight the discursive choices made by Babylonian rabbis in their legislation regarding demons, and in their constructions of the demonic.

In my examination of demonic discourse in the Babylonian Talmud, I make three central claims. First, the rabbis neutralized the threat of demons by subjugating the demonic to rabbinic halakhah. Second, the rabbis treat demons in the same way that they treat other topics recognized by later readers as normative. I demonstrate that, in fact, demons were an important part of normative rabbinic law for the Babylonian sages of the Talmud. Third, rabbinic discourse about demons is part of a much larger cultural matrix of demonic discourse in Sasanian Babylonia, in which ancient Mesopotamian beliefs about demons existed side-by-side with contemporaneous Zoroastrian, Manichean, and Syriac Christian demonic discourses. I argue that the rabbis constructed demons as subjects of rabbinic law in ways that adopt, adapt, and reject particular cultural options available to them. When rabbinic demonic discourse is fully contextualized, it becomes clear that it aligns in content with ancient Mesopotamian discourse about demons, but in form with contemporaneous Zoroastrian legal discourse about demons. This act of cultural bricolage results in the creation of a uniquely rabbinic perspective. In order to make these claims, this dissertation is organized in concentric circles beginning with rabbinic law, and expanding outward to include rabbinic narratives, material evidence, and Ancient Mesopotamian, Ugaritic, Zoroastrian, Armenian, and Syriac Christian parallels and approaches.

The first chapter reviews previous scholarship on demons in ancient Judaism and religious studies more broadly and lays out the theoretical model for my study of those ancient texts which deal with demons. My work draws on the Foucauldian theory of discourse, advances in the study of religion and magic within both religious studies and social anthropology, the French field of ethnopsychiatry, and the renewed interest in situating the Babylonian rabbis within their Iranian cultural context, in order to take seriously the ways that the rabbis talk about demons, and the ways demons function in real and embodied ways in their literature.

The second chapter examines one extended passage in the Babylonian Talmud (b. Pesaḥim 109b-112a) using source criticism, form criticism, and redaction criticism, in order to create a basic model of Babylonian rabbinic demonic discourse. I argue that the Babylonian rabbis neutralize demons by turning them into subjects, informants, and teachers of rabbinic law, thus subjugating them to the legal system. When demons are subjugated to rabbinic law, the very nature of what it means to be a demon changes: as demons become neutral, rather than necessarily malevolent beings, they do not harm the rabbis and their followers. Instead, the demons themselves have become followers of the rabbis.

The third chapter highlights those areas where the Babylonian rabbis differed from the Jewish traditions they inherited, by comparing demonic discourse in the law and narratives of the Babylonian Talmud with those of Second Temple literature and Palestinian rabbinic literature. I show that the Palestinian rabbis continued earlier Second Temple period (third century BCE through first century CE) models of demonology that focus on narratives of demonic origins. By contrast, while the Babylonian rabbis retained many of the narrative themes found in Second Temple Literature, they also chose a new approach and dealt with demons through halakhic (legal) discourse. I argue that the Babylonian rabbis recognized that their approach to the demonic was different from that their Palestinian confreres – as did the Palestinian rabbis – and this difference became an important part of each community’s self-differentiation from the other.

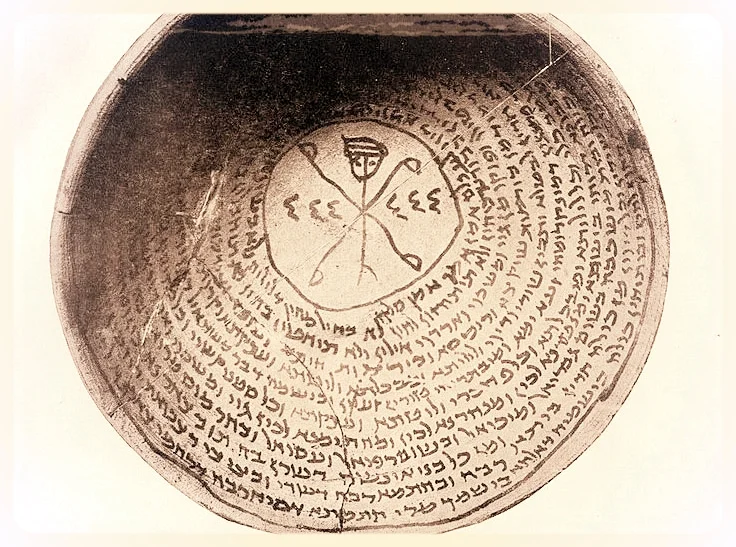

The fourth chapter contextualizes Babylonian rabbinic demonic discourse within early Mesopotamian, Ugaritic, Zoroastrian, Armenian, and Syriac Christian literatures, as well as the Babylonian incantation bowls. Though the demonology of the Babylonian Talmud has often been dismissed as Persian superstition, I suggest that, in fact, it was neither Persian nor superstition. I show that Babylonian rabbinic demonic discourse aligns in content with earlier Sumerian and Akkadian understandings of the demonic, and adopts only the form of legal discourse from the contemporaneous Zoroastrian elite. My purpose is not to argue that there was direct borrowing or influence, but rather to situate rabbinic demonology within the wider cultural network of Sasanian Babylonia in order to highlight the particular discursive moves of the Babylonian rabbis. The alignment of the content of rabbinic discourse of demons with earlier Mesopotamian understandings of the demonic, against contemporaneous Zoroastrian and Christian demonic discourse is thus an important data point as scholars continue to determine the relationship, and interrelationships, of Babylonian rabbinic and Sasanian texts and ideas.

In my conclusion I argue that rabbinic discourse related to demons functioned to situate the rabbis as a religious and intellectual elite distinct from and empowered over non-rabbinic Jews of Babylonia. Using the form of legal discourse, the rabbis aligned themselves with elite Zoroastrians. Yet paradoxically, while this discourse contributed to the construction of a rabbinic elite, its disinterest in engaging with Mandaean and Manichaean demonological traditions meant that non-rabbinic Jews would continue to turn to multiple non-rabbinic sources of authority to deal with those demons ignored by the rabbis. The bowls in particular attest to a widespread belief in a range of demons that crossed religious boundaries; the refusal of religious literary elites to recognize and interact with these more widespread beliefs meant that believers continued to turn to different ritual specialists for apotropaic and exorcistic rites. Thus, non-rabbinic Jewish eclecticism is, to some extent, a product of the rabbinic self-perception as a particular, insular, type of elite.

My conclusion further extends the study of rabbinic demonology to discussions of monotheism in the ancient world, arguing that for the rabbis, monotheism was a messy construct which allowed for autonomous intermediary beings, while the integration of demons in monotheism also allowed the rabbis to differentiate themselves from their dualistic and Trinitarian neighbors. My conclusion also makes explicit my work’s contribution to the refinement of broader theories of demons, magic, and religion, by situating demonological concerns within the realm of normative religion and not that of non-normative magic. Exploring those areas of religious tradition that have been dismissed as non-normative or folkloristic allows us to uncover values, relationships, and strategies previously unknown not only in the field of Jewish Studies but also in the history of ideas and the study of theology inLate Antiquity.

In this dissertation, then, a sustained examination of a single sugya in b. Pesaḥim is expanded outwards and contextualized so as to shed light on rabbinic demonology as a whole, rabbinic legal discourse, inherited interpretive traditions, the shared cultural networks of Sasanian Babylonia, and theological competition in the Late Antique world.

Sara Ronis is a Starr Fellow in Judaica at Harvard University.