Sacred Slaughter: The Discourse of Priestly Violence as Refracted through the Zeal of Phinehas in the Hebrew Bible and in Jewish Literature (Harvard University, 2015)

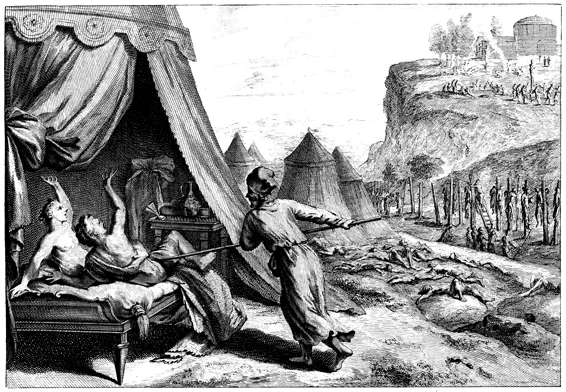

The story of Phinehas’ zealous slaying of an Israelite man and the Midianite woman with whom he dared consort in public (Numbers 25) is perhaps the most notorious of a number of famed pentateuchal narratives that contain vigilante violence. Significantly, a number of these narratives feature members of the Israelite priesthood or their eponymous ancestors. When reading these texts together, we uncover a consistent literary undercurrent which associates the priesthood with acts of interpersonal violence –– a phenomenon which I refer to as the motif of priestly violence. This dissertation examines the origins and discursive functions of this motif, and, employing the violence of Phinehas as a test-case, explores its interpretive afterlife in biblical and Jewish literature.

I argue that likely driving the motif of priestly interpersonal violence is the cultural memory of the violence of the sacrificial cult –– be it the violence inherent in the slaughter of animals, or the possible Israelite prehistory of human sacrifice. Despite these seemingly negative associations, the discourse of priestly violence functions as a critical legitimating component of the priestly imagination in the Hebrew Bible. Indeed, numerous biblical texts insinuate that it is violence, not the right lineage, that generates priestly identity. Exploring the Nachleben, or afterlife, of Phinehas’ famed violence, I demonstrate how ancient readers of the Hebrew Bible recognized and were sensitive to these facets of the motif.

I further highlight the continuities in the uses of the legitimating function of Phinehas’ violence in the Jewish literary tradition. From the literature of the Second Temple period through the rabbinic canon and continuing through the medieval midrashim, Jewish authors employed Phinehas’ violence in the service of their own discourses of group (de)legitimation. Priestly groups with questions about their pedigree, such as the Hasmonaeans, appropriated the discourse of Phinehas’ violence as a bulwark against the contestation of their priestly identity. But we also find subversive uses of Phinehas’ violence, particularly in Palestinian rabbinic texts, which question the integrity of Phinehas’ priestly lineage as well as the propriety of his lethal zeal. This serves to delegitimize the priesthood and effectively quash any lingering priestly claims to ritual leadership.

In the first part of the dissertation, I introduce and define the motif of priestly violence. I then provide a number of theoretical frameworks for understanding the possible origins of the motif, each of which draws links between the violence of sacrifice and the literary portrayals of interpersonal priestly violence. My analysis further demonstrates how violence is tightly and inextricably bound with priestly self-perception. I then contextualize Phinehas’ famed zeal within the larger framework of the biblical motif of priestly violence. My findings reveal that priestly violence relates closely with the violence of sacrifice, intergroup polemic, and anxieties about the contestation of (priestly) group identity.

In the second part of the dissertation, using Phinehas’ violence as a test-case, I explore the reception of priestly violence in inner-biblical and post-biblical literature. I explore how ancient writers judged Phinehas’ violence, and whether they sensed, or even made use of, the motif of priestly violence. Thus in Chapter 2, I examine the legacy of Phinehas’ priestly violence within the Hebrew Bible itself. I argue that already within the Hebrew Bible there may have been a struggle with comprehending or giving approbation to Phinehas’ spontaneous violence. Nevertheless, priestly writers continue to maintain Phinehas’ association with violence, albeit without ever again mentioning his famed zeal from Numbers 25.

Chapter 3 moves forward to the literature produced during the Second Temple period. It seems natural for Phinehas to figure prominently in this literary setting, given the strong interest during the period in the legitimacy of the priesthood, or specific bloodlines thereof. I demonstrate how this is certainly the case in 1 Maccabees, and to a lesser extent, in Jubilees, both of which appropriate Phinehas’ violence (or aspects of it) in support of the discourse of priestly legitimacy. On the other hand, I grapple with the conspicuous and mysterious absence of Phinehas from the writings of the Qumran sect, this despite its seeming preoccupation with priestly legitimacy. Continuing later into the Second Temple period, I turn to the writings of Philo, Josephus, and Pseudo-Philo, each of whom provide lengthy recapitulations of Phinehas’ deeds, but contend with Phinehas’ violence in very different ways. In the case of all three writers, and despite their disparate uses of his violence, Phinehas remains central to discourses of (de)legitimation.

In Chapter 4, I turn to the reception of Phinehas’ violence in the classical canon of rabbinic literature. One would expect, a priori, that the rabbis would distance themselves from the dangerous precedent of Phinehas’ violence, particularly given their legal and political subjection to foreign empires. It is thus surprising that the Mishnah integrates Phinehas-like violence (and other provisions of priestly violence) into the rabbinic legal system, and that the Sifre highlights Phinehas’ heroism with numerous embellishments to the biblical narrative.

I demonstrate how, nevertheless, the Palestinian Talmud and Sifre subvert the function of priestly violence by overtly criticizing Phinehas’ violence and questioning the integrity of his priestly lineage. I ascribe these critical moves to lingering rabbinic anxieties about the priesthood, with the persona of Phinehas functioning as a cipher for the priesthood at large. On the other hand, I illustrate how the Babylonian Talmud seems warmer toward Phinehas’ violence and recognizes its clear priestly underpinnings. I point to the curious fact that the Babylonian Talmud reserves its criticism for Moses, an interesting continuity with the interstices of the narrative in Numbers 25. This move I likewise characterize as a discourse of (de)legitimation, with Moses here representing (the somewhat subversive) intramural concerns about the rabbinic project at large.

Chapter 5 assesses the continued interest in Phinehas and his priestly violence in three post-talmudic Jewish compositions dating as late as the 13th century CE. In the earliest of these compositions, Pirqei de-Rabbi Eliezer (PRE), Phinehas is lavished with praise, the scope of his violence is extended, and his killing of Zimri and Cozbi is explicitly correlated, limb by limb, with his being awarded the sacrificial parts. I contextualize this positive portrayal of Phinehas as part of the wider priestly sympathies of the work. Similarly positive attitudes toward Phinehas’ violence (and priestly violence in general) are found in two midrashic anthologies, Pitron Torah and Midrash ha-Gadol. The former displays a concerted emphasis on the legitimacy of Phinehas’ priestly lineage, a move that I situate within the documented polemics over priestly lineage around the time of the work’s composition.

My work has wider implications for understanding the origins of religious martyrdom. Indeed, I argue that the biblical motif of priestly violence is best understood as the progenitor of the post-biblical Jewish martyrology. Long before religious pietists gave their lives for the sake of the law, religious zealots are portrayed as taking lives for the sake of the law. I therefore present priestly violence as “proto-martyrdom” and illustrate how this paradigm prefigures the highly stylized discursive functions of its better-known successor. This schema can be tested in other religious corpora with exhortations to violent zeal, on the one hand, and martyrdom, on the other.

In addition, this project demonstrates that the intergroup polemics in the interstices of the biblical text, far from being a modern scholarly construct, were both detected and put to use by ancient Jewish writers. As scholarship on rabbinic texts is experiencing a resurgence in comparative studies with non-Jewish literary canons, my work reveals that there remain ample avenues for the rediscovery of the Hebrew Bible within the study of ancient Jewish texts.

Yonatan Miller is a Starr Fellow in Judaica at Harvard University.