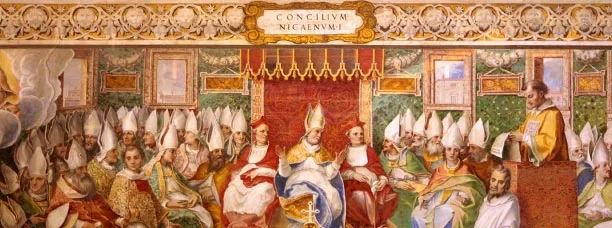

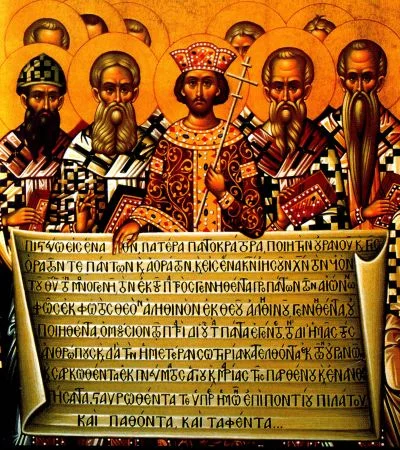

In the spring of 2014, the Religious Studies Department of Duke University offered a new course: “Debating Jesus: Christian Theological Debates in their Historical and Cultural Contexts.” Through “debating Jesus” Dr. Cavan Concannon hoped to introduce students to the contentious nature of this formative period for late ancient Christian discourse. Students were expected to analyze the Council of Nicaea, specifically the competing articulations of Trinitarian doctrine and visions of ecclesial organization through a historical approach. However, unlike survey courses of early Christian history, Dr. Concannon constructed the syllabus around a dramatic re-enactment of the council using the pedagogical materials of Barnard’s Reacting to the Past curriculum. As the teaching assistant for the course, I experienced first hand the challenges and rewards of guiding students through a complex role-playing game, which allowed them to enter into the tense negotiations of Nicaea

While the course was intended as a study of the historical events leading to the Council, the nature of the debates surrounding Nicaea also demanded a level of theological literacy and familiarity with the issues at stake for various early Christian groups. The students in the course represented a wide variety of backgrounds and levels of exposure to the New Testament and Christian theological categories, creating both an opportunity and a challenge since the success of the game depended on students having a firm grasp of the theological positions at play.

The first six weeks of the course were dedicated to lectures presenting key Christian figures and groups. The sweep of texts and thinkers was impressive: the apostle Paul, Marcion, the Nag Hammadi texts, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus and Origen – only to name a few. Students read primary sources along with secondary texts such as John Behr’s The Way to Nicaea and Bart Ehrman’s Lost Christianities. In addition, the Reacting to the Past curriculum written by David E. Henderson and Frank Kirkpatrick included a student game guide with some additional historical materials and important rules for how the Council of Nicaea would be re-enacted. The students were aware from the first day of class that as council members they would undertake the task of drafting a creedal statement and passing a series of canons based on those actually discussed at Nicaea.

An integral part of the course was assigning students a “character” whose identity they would develop through the course of the semester and would eventually assume for the game. The curriculum materials included detailed descriptions of each role with a list of objectives that had to be achieved in order to score points. These goals were tailored to the character’s theology, motivations, and objectives, and students were expected to write speeches, engage in debate with their peers, and to build alliances in order to meet these goals. Part of the game’s complexity is the number of goals for each character, ranging from persuading the council to agree to a specific wording in the creed to getting certain canons approved or entirely struck down. A certain degree of secrecy was also required, so these individualized character descriptions were to be kept private.

Given the popularity of the course – upwards of forty students were enrolled – we were able to run two separate councils concurrently for the three weeks of game play. Dr. Concannon would supervise “Nicaea North” while I oversaw “Nicaea South.” This meant that within the class two students would portray each character, allowing for a degree of collaboration in their preparation.

By the second week of class each student was assigned a role and provided with the biography from the game materials. One student would oversee the council as Emperor Constantine whose main objective was building unity and bringing about a stable ecclesial structure. Some of the characters were familiar figures from the council, Eusebius of Caesarea or Athanasius, but other roles were inspired by the historical issues at play. “Theclus,” for example, advocated for a greater role for women within emerging church structures while the “Bishop of Memphis” advocated an expansion of the proposed canon to include the Secret Gospel of Mark, as well as the Gospels of Philip and Mary Magdalene. The inclusion of characters who represented “Gnostic,” Marcionite, and subordinationist Christologies meant that the game would not strictly mirror the constituency of the original Council, but rather provide students the opportunity to explore a range of early Christianities. Students were fully aware of this disconnect between the historical reality and their own Council, and they showed an impressive sensitivity to how these adjustments allowed them to further re-imagine the diversity that existed within the first centuries of Christianity.

During the opening weeks, students were expected to strategically position themselves within the council, and early writing assignments were designed to help them inhabit the voice of their character. They were to read the primary sources (especially the biblical texts) with an eye to passages that would bolster their arguments and counter the claims of their opponents. Drafting speeches, language for the creed, and possible canons required students to pay meticulous attention to the theological and political ramifications of subtle changes in language. Modern technology enlivened the experience for students by allowing for live tweeting of council developments and secret negotiations via email.

As an instructor, the weeks of game play demanded a good deal of attention to the dynamics of the council and to “behind the scenes” negotiations. It was also an opportunity for motivated students to make the most of their character’s potential, and the fiery speeches of our “Arius” as well as the penetrating biblical insights of our “Athanasius” provided the council with dramatic moments. Several students also experienced the frustration of finding little sympathy for their objectives, while others struggled to weigh what goals they could sacrifice in negotiations. It was extremely rewarding to see the impassioned nature of these theological debates and the intellectual dexterity of the students as they assumed historical personas that only weeks earlier would have been mere figures in the pages of a history book.

The two councils yielded distinct creedal statements and canons that differed from the historical Nicaea. For example, one of the creeds lacked the precise language of the Nicene Creed, allowing those with subordinationist Christologies to sign onto its final form and avoid excommunication. Both councils also allowed for female ordination with little debate – a far cry from the historical reality and an intriguing indicator of how the younger generation reflects on current debates about gender and ecclesial authority. In the final weeks of the course, students discussed the outcomes of their two councils while receiving an overview of the results of the historical Nicaea, and comparing it with their own outcomes.

As a young scholar and teacher, I look forward to more opportunities to incorporate these pedagogical techniques as a way of moving beyond historical narratives that dismiss the debates of the early centuries of Christian discourse as arcane wrangling over minor philosophical points and theological language. I believe inhabiting the voices and perspectives of these characters allowed students to sympathize with these individuals and to form thoughtful critical analysis of the issues and the consequences of these historical events. The lively nature of the debate also tapped into a youthful exuberance for weighing competing points of view that was inspiring for student and instructor alike.

Erin Walsh is a PhD Student in Early Christianity and Late Antiquity at Duke University.

You can follow Erin on Twitter @ErinCGW.