Olympians in D'Aulaires' Book of Greek Myths

“As an occasional series, “Unexpected Influences” asks scholars to reflect upon one book outside their respective fields that influenced their scholarship.”

Dr. Adele Reinhartz

In the mid-1990s I was struggling with the introduction to a book on a “Jewish reading” of the Gospel of John, the New Testament book with which I have been preoccupied off and on since my doctoral dissertation in the early 1980s. During this period, I happened to attend a lecture on Job given by Carol Newsom. Carol’s talk began with a reference to Wayne Booth that sent me directly to his marvelous book, The Company We Keep: An Ethics of Fiction (1988). Booth argues that our relationships with important books in our lives are analogous to our relationships with our friends. With books as with friends, we should not drift along in easy companionship, but rather engage them with integrity, understanding and honesty. The metaphor of book as friend provided me with a title (Befriending the Beloved Disciple: A Jewish Reading of the Gospel of John [2001]) and a productive framework through which to articulate my fraught relationship not only with the Gospel of John, but with other biblical texts that continue both to fascinate and frustrate.

Adele Reinhartz is Professor in the Department of Classics and Religious Studies at the University of Ottawa, in Canada. @adele_reinhartz.

Dr. Andrew Jacobs

In light of my doctoral advisor's recent intellectual autobiography, published in the winter 2015 issue of the Catholic Historical Review, I've been pondering a moment in my very first graduate seminar with Elizabeth Clark. We were reading her recently published and astounding book, The Origenist Controversy: The Cultural Construction of an Early Christian Debate (Princeton, 1992) and discussing the watershed in scholarship on Evagrius Ponticus following the publication of Antoine Guillaumont's Les "Képhalaia gnostica" d'Évagre le Pontique et l'histoire de l'origénisme chez les Grecs et chez les Syriens (Du Seuil, 1962). Liz Clark sighed wistfully and remarked how she wished she had written that book. I (in my head) sighed wistfully and thought, "If only I could write a book like Liz Clark's The Origenist Controversy!" Oh, the power that others' books hold over our intellectual aspirations!

As this "unexpected influences" series for Ancient Jew Review illuminates, however, the books that have the most profound intellectual impact on us may not be those we encounter in our classrooms or conferences. Pondering my own "unexpected influences," two books immediately came to mind.

1. Anne McClintock, Imperial Leather (Routledge, 1995). In the misty days before I formally proposed my dissertation topic, I knew I wanted to approach Christian writings about Jews as a species of imperial cultural production. I knew almost nothing about postcolonial theory, so I began to read voraciously (Duke University in the 1990s was a great place to dive into theory). I can't remember precisely when in this process of intellectual consumption I first read Imperial Leather, but its traces still linger not-so-lightly over my work today. Set aside the brilliance of the writing, which still dazzles. Set aside the detailed footnotes which rivaled even those of Liz Clark. The manner in which McClintock engaged in historical analysis that drew on and explicitly reflected upon critical theory was eye-opening, prodding me to move beyond my heretofore somewhat clumsy "toolbox" approach to theory ("will the wrench of Foucault loosen this ancient Christian text, or the pliers of Derrida?") to a real contemplation of what historical writing could be, and how it could engage fundamental questions of personhood and community through theoretical engagement. McClintock's feminist postcolonial analysis challenged the canons of feminist critical theory as well as postcolonial analysis, all while engaging in insightful close readings of the material remains (visual and textual) of Victorian imperialism. Imperial Leather was a theoretical and historical revelation, the implications of which I am still processing.

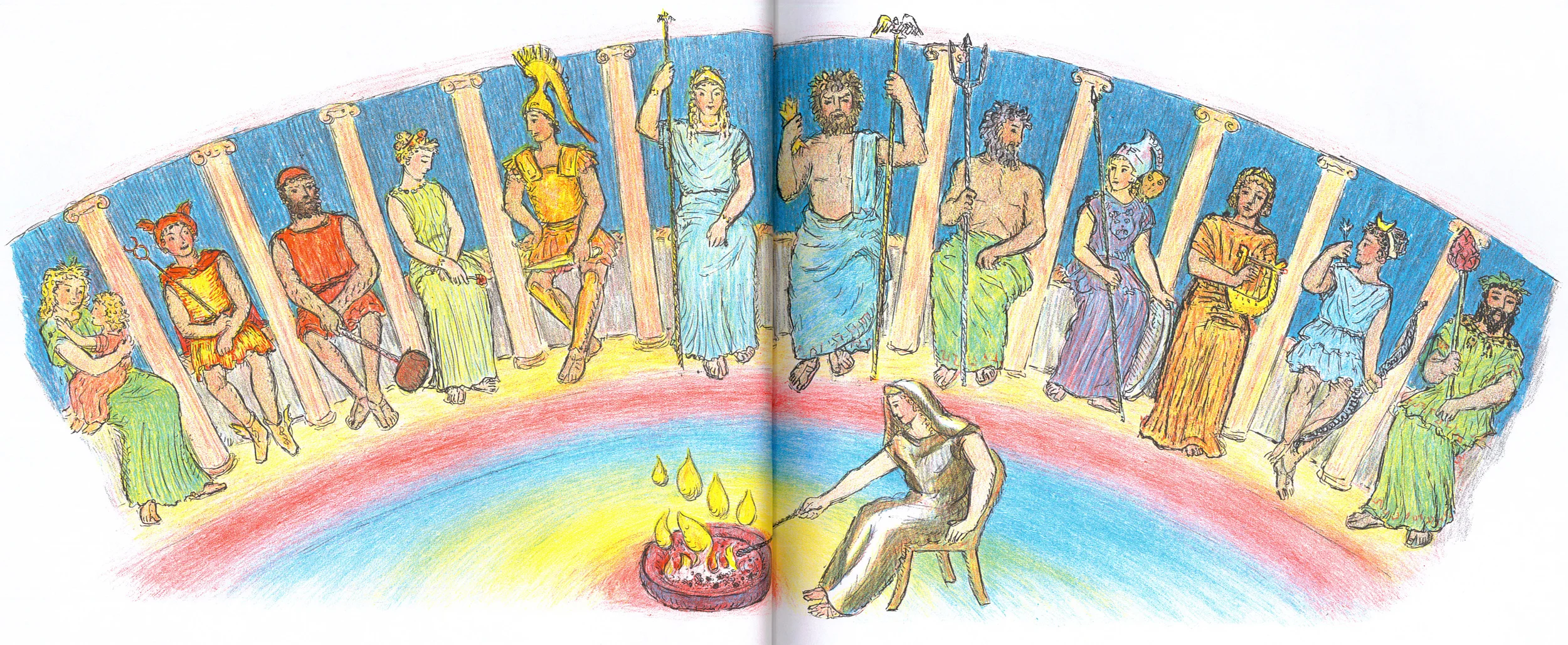

2. Ingrid and Edgar Parin D'Aulaire, D'Aulaires' Book of Greek Myths (Delacorte, 1962). When I was a very small child (I think around the age of seven) my parents bought me this colorful and surprisingly detailed children's book of Greek mythology which opens with the lyrical sentence, "IN OLDEN TIMES, when men still worshipped ugly idols, there lived in the land of Greece a folk of shepherds and herdsmen who cherished light and beauty," followed by idiosyncratic illustrations and only lightly bowdlerized accounts of Greek gods and heroes. I must have expressed a vague interest in ancient mythology, and my guess is that my parents asked at the local bookstore for something they could give their child to read. I inhaled it, probably hundreds of times, cover to cover. From there I moved on to other accounts of ancient myths suitable for "young readers" (Bulfinch, Hamilton), historical novels, nonfiction…the stream of books is lost to memory at this point. By the time I arrived at college, and needed to find some classes to take during the scrum of orientation week, two courses stood out that played to my nascent interest in ancient myths and religions: "Christianity in Late Antiquity," taught by Susan Ashbrook Harvey, and "Worlds of Late Antiquity," taught by Joseph Pucci. I enrolled for both, and my academic trajectory was set. I still own that worn copy of D'Aulaires' Book of Greek Myths (its lovely dust jacket long disintegrated), from which I nostalgically but accurately trace a direct line to my career as a scholar of late antiquity.

Andrew Jacobs is Professor of Religious Studies and Chair of Religious Studies at Scripps College. @drewjakeprof