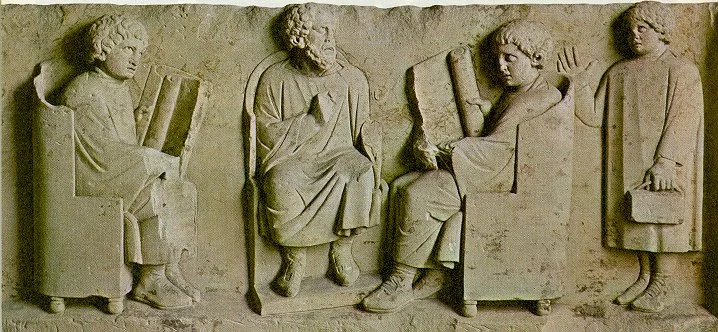

Relief in Neumagen near Trier, a teacher with three discipuli (180-185 CE)

Shayna Sheinfeld, Colgate University | Meredith J. C. Warren, University of Ottawa

As you prepare your syllabi for the upcoming academic year, consider using low-stakes writing assignments as an assessment option. Low-stakes writing assignments allow students to spend more time outside of class engaging with the course content and to come to class better prepared for class discussions.

What is it: Low-stakes writing assignments are frequent assignments given to students to explore their own ideas in concert with the readings and/or class activities. John C. Bean details this kind of exercise, which he calls Thinking Pieces, in Engaging Ideas: The Professor's Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2011). Low-stakes writing assignments are different from other assignments such as the short essay and the blog post. Short essays require students to write in a specific genre; low-stakes writing assignments allow students the freedom to grapple directly with the text without being concerned with the format of the assignment. Students have the freedom to explore in a non-linear way, focusing on content rather than format. Blog posts encourage students to think about their audience—often an audience of their peers. Thinking Pieces are meant to be a conversation between the student and the text; the student is writing only for herself. The low-stakes and informal nature of the assignment means that the student does not need to be concerned with audience.

In the past year, Shayna Sheinfeld and Meredith Warren both applied the concept in classroom scenarios at their respective universities. Shayna applied the assignment to her Great Books and apocalypse courses at Colgate University, while Meredith used Thinking Pieces in her upper level course at McGill University, The Ancient Christian Church: 54–604 CE. In both of our classes, students were engaging mainly with the primary source readings—both canonical and non-canonical texts from early Judaism and Christianity, as well as classical literature. In a page or less, students respond to a prompt through close examination of relevant texts, without being distracted by structure, grammar, or spelling. The main idea behind Thinking Pieces is that students grapple with texts and practice writing on a regular basis through short, no-pressure, low-stakes exercises.

How it works

Shayna: I used two versions of this assignment during the spring 2015 semester. In my introductory level Great Books-style course called Legacies of the Ancient World, I assigned 15 low-stakes writing assignment called Thinking Pieces that were worth 1% each, for a total of 15% of the final grade. With these Thinking Pieces I proposed an open-ended question that had students engage with a portion of the assigned ancient text. Students were required to turn them in during class and I did not accept late Thinking Pieces. I had two types of questions that I proposed during the semester: one had students thinking about a specific topic or wider theme in preparation for a planned class discussion (e.g. for Genesis 6–9 and our examination of the afterlives of the Flood narrative, “Discuss Noah's relationship to the divine—how do Noah and God communicate? Is this indicative of other human-divine interactions we have seen?”). The second type of question required the student to examine a topic or theme that I would not be addressing during class discussion (e.g. when we read the Gospel of Matthew, “Compare the birth narrative of Jesus with the birth narrative of Moses. Where are the similarities? Where are the differences?”). This second category of questions requires students to engage more carefully with specific questions not covered in class that would be useful for them in broader discussions or on other assignments and exams. Thinking Pieces were spread throughout the semester and were never assigned on a day another assignment was due.

The second course in which I used the low-stakes writing assignment was my upper level End of the World class. Unlike in my Legacies course, I had a set guideline for this assignment, which I called “says/does.” I required 17 says/does pieces, but this time they were worth 3% each for a total of 45% of the final grade, with the two lowest grades dropped. For each text marked in the syllabus—a mixture of primary and secondary readings—students were required to read and examine the text and to develop three main themes/topics. For each of these themes, students would have to paraphrase what the text said (the “says” portion), and then examine it for its broader implications, purpose, or function (the “does” portion). If the reading in question was a secondary source, like an article, students would also have to restate the thesis of the article.

Meredith: I used Thinking Pieces in my winter 2015 class at McGill University, The Ancient Christian Church: 54–604 CE. For that class, I assigned 16 prompts in advance, assigned to certain days on the class schedule. As with Shayna, I did not assign Thinking Pieces on a day when another assignment was due. Together, the Thinking Pieces were worth 15% of the total grade, with the lowest mark dropped. I did not allow late Thinking Pieces, and students were required to turn them in during class. The first Thinking Piece required a response to the prompt, “What do you think you know about the ancient Christian church?” This question gave an example of the assignment, allowed me to gauge the level of general knowledge of the class, and encouraged the students to reflect on some of their assumptions about the topic. Some prompts, such as “To what extent does the idea of supersessionism rely on the idea of a ‘parting of the ways?’” required students to interact more intimately with the primary and secondary texts they read and to synthesize concepts discussed in class. Others required reflection on class activities; after a field trip to the Rare Books holdings at the library, where students touched, looked at, and smelled (!) ancient papyri, codices, and ostraca, students wrote about how interacting directly with early Christian artifacts is different from or similar to reading about them. Likewise, after a class activity where students performed portions of Origen’s homilies, they analyzed the difference between performing a text in the context of liturgy versus reading one for study. The Thinking Piece prompts were spread out over the semester, with about two class sessions between each.

Other Assignment Details: As the above examples show, there are a number of ways to personalize Thinking Pieces for specific pedagogical purposes; the common thread is that the assignments are (a) brief; (b) regular; and (c) low-stakes. Both of us required students to keep responses to no more than one page, single-spaced. Shayna required that her students type the pieces, while Meredith allowed students to hand-write if they preferred. The strict length requirement requires students to learn how to be precise in their language and forces them to engage with the text(s) directly—there is no room for filler. Thinking Pieces were graded based on whether or not students had 1) addressed the question, 2) engaged with the text on a critical level, and 3) stayed within the page limit. Points were not taken off for grammar, spelling, or even if the student came to a wrong conclusion (something that could be addressed in comments or in class).

Why it works

Students become accustomed to writing critically because each assignment is less pressure than a formal essay; the frequency creates a classroom culture of consistently working through ideas before class. Students are more likely to come to class not only prepared but having really thought about the texts ahead of time, a finding supported by Meredith and Shayna’s experiences in class discussions and reiterated in student evaluations. For instance, one student comment from Meredith’s Ancient Christian Church class wrote: “The frequent ‘thinking pieces’ allowed you to more deeply explore the texts and prepare you for class discussion.” A student from the End of the World class wrote that the says/does pieces “really help you understand what each of the dense pieces [of text] are saying and why they are saying it. Also, it aids in comparing texts to see similar and contrasting features across apocalyptic literature.” Another student noted that “I’ve never been asked to think about what a piece of literature does.”

While low-stakes writing assignments may not be taken seriously by all students, in our experience using Thinking Pieces as a guiding tool ensures that ambivalent students who might not ordinarily do the reading carefully end up interacting critically with the sources, even if that engagement is only cursory. The subsequent discussion in the classroom, in our experience, encourages all students to engage more fully because of the social pressure of in-class discussions. The Thinking Pieces also allow us as instructors to get feedback about how students are learning. With these assignments, we can quickly and easily see if important concepts and/or techniques are understood or if certain topics need to be revisited or re-emphasized.

It should be noted, however, that not all students enjoy the low-stakes writing. In fact, for Shayna’s says/does pieces, students complained quite a bit at the beginning of the semester. While these were low-stakes, students reported that they spent a couple hours on each assignment, mainly in the time they spent engaging with the primary source in order to discern major themes. However, while Shayna’s students were initially resistant, they reported that although they did not like the assignment, the activity did get easier, and by the end of the semester they appreciated having spent the time on their analysis. As instructors, in our book this speaks to the success of Thinking Pieces. As Bean notes (124), being explicit with your students about the purpose and value of these exercises goes a long way to combatting student indifference to the assignment.

How to Manage Grading

It may seem that assigning Thinking Pieces in your course would raise your grading load to unmanageable levels. There are a few ways to handle the apparent increase in work. First, severely limit the word count or length for these assignments. Being strict with the length not only cuts down on the amount of reading you have to do, but also forces students to practice concision in their thinking and writing. Over time, concision in writing becomes habit, a benefit that also seeps into essay writing, making grading essays, if you assign one, more efficient. Another route, since this is a low-stakes assignment, is simply to not read all the exercises (Bean 123). We recommend that, at the very least, for the first few assignments you read every piece that is turned in. This helps you get to know your students, learn their style, answer questions that they may have, and address any glaring issues in how they approach the exercise. If you cannot read every one, you have numerous options. One option is to decide from the beginning to read only a random sample. After the initial few, Shayna chose to read a handful each time, making sure she rotated through the class list, and gave the others full points for turning them in. Or, read a few and skim the rest, as Meredith did. Since each piece is worth only a small portion of the final grade, there is some flexibility in how you choose to grade them throughout the semester.

Finally, low-stakes assignments mean grading rubrics can be simplified. Bean suggests a simple “check/plus/minus” system (142). Assignments that meet requirements for length and engagement with the prompt and/or assigned source receive a check; a contribution that is especially well written or engaged gets a plus, while a piece that is inadequate in length or depth receives a minus. Both Meredith and Shayna used a modified version of this low-stakes grading system; each Thinking Piece was graded out of 1 point, making it very easy to either assign the full point or take off half a point if necessary. For the says/does pieces, since they were worth 3% and covered three themes/topics, each topic was worth one point consisting of half a point for the “says” portion and half a point for the “does” portion.

Conclusion

Shayna and Meredith each applied low-stakes writing assignments in different contexts; whether in a Great Books-style survey course or one focused on a specific corpus of texts, a particular time period, or a particular theme, low-stakes writing promotes in-depth student engagement with sources, better preparation for class sessions, and overall, a more thorough understanding of course material.

“Do you have a creative tool or method for teaching late antiquity? Share it on AJR!”