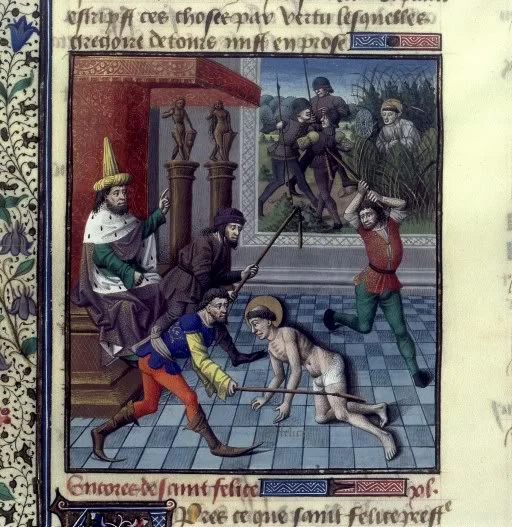

St. Felix

Fruchtman, Diane Shane. Living in a Martyrial World: Living Martyrs and the Creation of a Martyrial Consciousness in the Late Antique Latin West. Ph. D. dissertation, Indiana University, 2014.

"Living in a Martyrial World" demonstrates the necessity of recognizing that, in Christian traditions, martyrdom does not always require death. Challenging the current scholarly custom of marking death as a criterion of martyrdom, I investigate the attempts of early fifth-century Latin authors to make martyrdom accessible to the masses (despite the end of official persecution in the fourth century) by creating new paradigms of martyrdom that did not demand the martyr’s death. Prudentius (348-405), Paulinus of Nola (352-431), and Augustine of Hippo (354-430) each championed “living martyrs”—martyrs who earned their status by some means other than dying in persecution—and through rhetorical techniques, biblical realism, and outright exhortation each author sought to extend that martyrdom to their audiences, allowing their contemporaries to develop martyrdom-based worldviews to reinforce their identities as Christians.

In my introduction (“Rethinking Martyrdom”), I demonstrate that theologians and secular scholars alike dismiss the concept of living martyrs. After exploring the consequences of this dismissal, I hazard a new definition of martyrdom, one that retrieves from my sources an emphasis on “witness” (the original Greek meaning of the term “martyr”) and focuses on the work that would-be culture-makers sought to accomplish with their constructions of martyrdom: a martyr is “an individual who, by virtue of suffering, willingness to suffer, mimetic identification with an exemplary sufferer, and/or death, is employed by an author or community to serve as witness to some communally accessible truth.” Martyrdom, then, is however an author configures a martyr to have accomplished this witness. So, for Encratis, the violenta virgo of Peristephanon 4, her martyrdom consists in all the features of her story that Prudentius adduces to present her as witnessing to Christian truth—namely, her torture, the death of her severed flesh, her continued suffering, and, most importantly, her survival to recount her own experience. This definition is neither emic nor exhaustive but aims to facilitate better recognition of when and how martyrdom discourse is used.

Chapters 1 and 2 (“Destabilizing Death, Advocating Witness: Prudentius’s Peristephanon” and “Modeling the Living Martyr: Witness in and through Poetry”) explore the martyrological poetry of Prudentius, looking at the myriad ways the poet advocates dissociating martyrdom from death. Prudentius uses his mastery of classical literary and rhetorical techniques to work on and within his readers, making his case both persuasive and seemingly intuitive. With death thus destabilized, witness takes its place as the signal characteristic of martyrdom. Prudentius ultimately seeks to teach his readers how to become living martyrs themselves through their own witness. Seeing, hearing, and feeling alongside the martyrs they encountered in Prudentius’s poetry, contemporary Christians could train themselves to see the world through Christ-colored glasses, developing a martyrial worldview resilient enough to withstand any historical circumstance.

Chapters 3 and 4 (“Paulinus of Nola and the Living Martyr” and “Making Martyrs in the Nolan Countryside”) turn to Paulinus’s martyrological program as he defends the martyr-status of his patron saint, Felix, despite Felix’s failure to die in persecution. In the process of championing Felix and other living martyrs, Paulinus configures martyrdom as an embodied reorientation to God, which he then attempts to inculcate in his audiences. Rather than advocating a shift in worldview alone, as Prudentius had done, Paulinus seeks to cultivate an ethic of imitation to complement that worldview. This imitation, like Prudentius’s worldview, relies on witness—but a problematized, elusive, and uncertain witness, since Paulinus constantly reminded his audiences that the saints’ true worthiness lay in an internal reorientation that only God could truly know. Thus, Paulinus both calls his audiences to imitation and trains them to seek guidance in their imitation from God and his Church.

Chapter 5 (“Non Poena Sed Causa”) addresses Augustine’s sermons, in which he explicitly asserts the non-necessity of death to martyrdom not only by reminding his parishioners that the word means “witness,” but also by repeatedly claiming that it is “not the punishment, but the cause” that makes a martyr, obviating the need for any punishment at all. The import and pastoral significance of this dictum have been until now overlooked, primarily because scholarly and confessional readers alike have brought to the text a lens that privileges death as the marker of martyrdom, such that causa becomes an additional condition for martyrdom, rather than its sole criterion.

My conclusion (“History, Historiography, and Power”) elucidates the scholarly correctives the dissertation offers. First, the historical corrective: our subjects’ definitions of martyrdom do not necessarily include death, and we need to interrogate their definitions to understand their spirituality. Second, a historiographical corrective: we must change our definition of martyrdom so we can better identify and analyze martyrdom discourse in any historical era. Third, a political corrective: we need to recognize both the power and range of martyrial discourse in order to see, understand, and potentially respond to the ways it is being mobilized in identity and community construction—whether that is in ancient texts or the modern American political scene.

This case study proves that the concept of martyrdom is historically contingent, that it is broader than can be appreciated if we establish death as its necessary component, and that to recognize its vast potential for deployment in self-fashioning, identity construction, and community-creation we cannot be blinded by definitions that hinge on death.

I am currently refining and expanding this project for a monograph to be titled, Surviving Martyrdom: Martyrdom without Death in the Late Antique West and Beyond.

Diane Shane Fruchtman, DePauw University