Are there canons before the canon? Does such categorization distort our view of the cultural production of ancient Judaism? Does the transmission of ancient Jewish texts into modernity both rest upon and exceed the boundaries of canon in different settings? After reading the three essays by professors Lim, Mroczek, and Breed in the canon forum hosted by Ancient Jew Review in December 2015, I have a better grasp of the difficulties surrounding the discussion of such a nebulous subject as literary, cultural, and religious(?) canons. Yet, by the time I reached the end of the initial installment of the forum with professor Crawford’s measured response, I found myself wondering about a more simple question: Given these difficulties, how does one recognize a canon?

Traditionally, this problem would have an easy solution: one looks to the modern Bible(s) and searches for similar-looking entities in diverse cultural and temporal settings. We see elements of this approach in Lim’s essay, wherein his starting point is the “Hebrew Bible” and “the one Jewish canon,” which though not yet attained before Yavneh (One wonders here what has been done with Lewis (1964), Beckwith (1985), Barton (1986), and Aune (1991) on the subject of the supposed council), existed in nuce in the Pharisaic authoritative scriptures among other similar bodies of literature. However, as Mroczek has made clear in her essay, there is danger in this teleological approach because “When we go looking for the Bible, we often find it.” That is, finding traces of a known entity in unexplored regions is an almost inevitable result. Her criticism of this etic approach to canon is well taken. Breed provides even further caution in noting that the very idea of the “Hebrew Bible” or “the one Jewish canon” is a construct that conflates various different collections under a single identity. It would seem that the traditional course of looking to later collections and working backward, then, is not viable. He argues for canon as a process, one that is never fully closed. I would like to delve into this concept further, as I think it may be fruitful to discern how one would recognize a canon under this paradigm of canon as process.

As Breed and Mroczek note, if we cannot begin with “the Bible” in order to recognize a canon, we certainly cannot elevate any given list produced in a specific location and at a particular moment in time as the model for what comprises a or the canon. While these lists are certainly part of a canonical process, in that they both reify and question what are the cultural, educational, perhaps even liturgical touchstones for a given community at a specific moment in their existence, no such list marks the end point or completion of canon. The same goes for any given codex or edition.

The canon, then, is always in progress. So, the search for canon must be re-centered by focusing not on the definitive list, which is after all a mythic construct, and instead concentrated upon the perennial process of iteration and reiteration of texts, traditions, and figures. Only in this way may we get closer to recognizing canons and their functions as diachronic exercises in the assertion of communal identities. That is, when we treat variety between and among lists and collections as defining characteristics of canons rather than the exceptions to them, we are forced to admit that canons change. In fact, they must change because communities that produce and transmit them are constantly in the process of change as well. As such, the concept of canon marks not a set point but a process that involves different kinds of adaptations over time and place.

This is all part of that reinterpretation and reassertion of canon. It is true that some texts, traditions, and figures seem to be asserted more rigidly in their form and contents by communities. However, even these enjoy constant reinterpretation and re-performance in ever changing contexts, both religious and profane. Most of these performative and interpretative contexts, as Breed has pointed out, are paradoxically able to assert authority over the texts, traditions, and figures traditionally considered canonical. Other texts, traditions, and figures only fleetingly or spasmodically enjoy such exposition and representation. These interpretative and performative environments, whether persistent or intermittent, are also a necessary aspect of recognizing change as central to canonical processes.

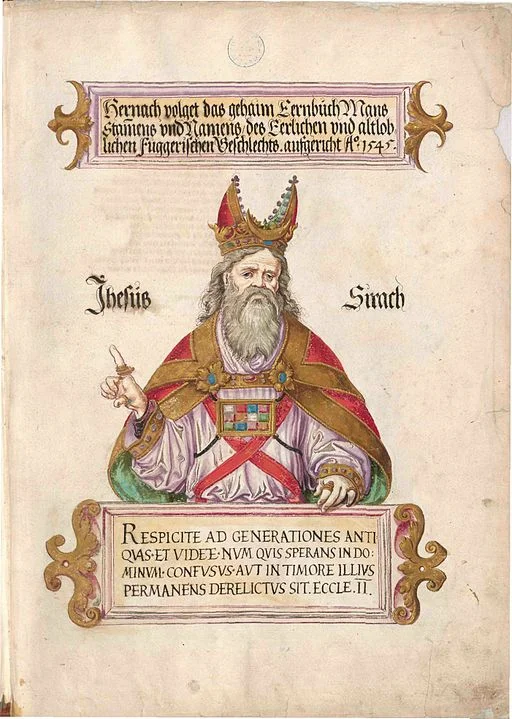

When this re-centering toward the “margins” occurs, we begin to see supporting evidence for canon as process in some of the most contentious places. For example, if we turn to the translator’s prologue of the book of Ben Sira, which has been proposed by some canonical hard-liners as early evidence for closing of the canon of the “Hebrew Bible,” we will note the progressive nature of the collections of texts discussed. Rather than a closed body of texts which represents the entirety of Israel’s contribution to education and wisdom, we notice that both Ben Sira’s Hebrew work and the Greek translation are introduced as endowments to that cultural heritage which both reiterate it and better it. In addition, the translator argues that it is the responsibility of “those who love learning” among his own audience to make similar contributions. Surely, Ben Wright, Lee McDonald, and others are correct in doubting the presence of a canon or proto-canon here, when this is defined as a closed list or collection. But when viewed as a perennial process of iteration and reiteration we may yet speak of canon in this context.

Another example comes from the second letter prefixed to 2 Maccabees (2 Macc 1:10-2:18, esp. 2:13-15). This text, too, has been used as evidence of an early canonical list attesting to the existence of the “Hebrew Bible” in the 2nd century b.c.e., a claim which certainly cannot withstand scrutiny under the traditional lens of canon. Aside from the fact that there is no Torah or nomos included in the list of textual authorities, the other categories, such as the letters of kings about votive offerings, or references to David (as Mroczek has shown), are far too vague to determine their relationship to known literary works. In addition, the bulk of the letter is predicated upon the authority of a story, ostensibly found in the memoirs of Nehemiah, which bears no relation to any other extant traditions related to that figure. In this text we see figures such as Moses, Solomon, and Nehemiah cited as authorities alongside a variety of texts in the context of a specific request for reiteration and memorialization of an ostensibly contemporary event (i.e. the feast of fire for the rededication of the temple). This is even concluded with an invitation for the addressees in Egypt to obtain copies of at least the written sources. In this story we can recognize that reiteration of texts, traditions, and figures may take a variety of forms, but still contribute to the process of canon.

A third example that might be cited of this process of reiteration and re-performance that lays at the heart of canon comes with the book of Jubilees 6:22. This verse makes reference to a “first law”, usually identified as the Pentateuch, or something resembling its contents, thereby presenting Jubilees itself as a second law. The fact that Jubilees is second or later, however, does not reduce its authority, or force us to understand it as an exegetical exercise. Rather, Jubilees is yet another performance of a tradition which both celebrates and adds to what has preceded it. The realization that such performances are asserting authority while adapting the basis of authority is necessary for the understanding of canon as process.

Many other examples, from ancient manuscripts to modern lectionaries, might be cited as instances of this process of reassertion and re-performance as necessary for the continued existence of canon, but the above will have to suffice. It should be clear, though, that because the concept and contents of a given canon rely on the process of reiteration, no single list, no single collection, can be considered definitive. This means every one of these reassertions of text, tradition, and figure, with all the variety they contain, must be included into our concept of canon. Canon is never finished.

Dr. Francis Borchardt

Assistant Professor of Hebrew Bible and Jewish Studies,

Lutheran Theological Seminary, Hong Kong