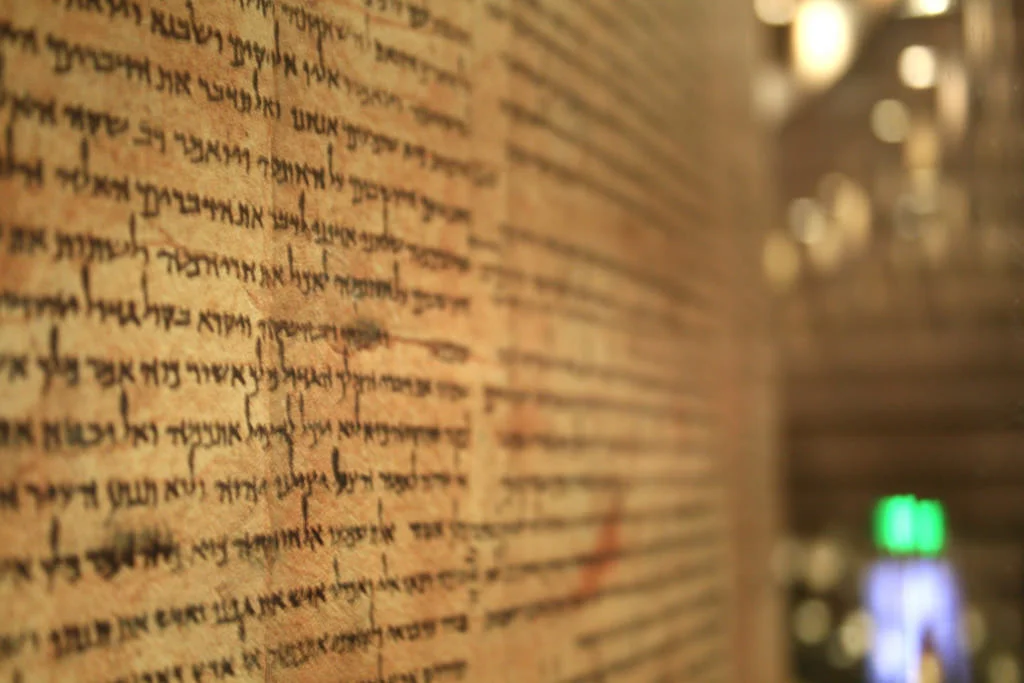

Material Aspects

Any discussion of the compositional growth of texts in light of the Dead Sea Scrolls must begin by acknowledging the material culture of these finds. We now have a much greater understanding of the sizes and features of ancient scrolls and the practical mechanics of constructing and copying them in the Second Temple period. This new appreciation of the realia of ancient scrolls and scribal practices forces us to think pragmatically about our theories of textual development and restrain some of our wilder speculations. Unfortunately, however, there are virtually no marginal annotations, collations of variants, draft copies, or editorial changes to manuscripts materially evident in the Dead Sea Scrolls, so we gain very little direct insight into the actual physical processes by which editing would have progressed.

Modes of Transmission

Another important question illuminated by the Dead Sea Scrolls is whether or not scribes attempted to replicate the texts of their exemplars or felt free to change their received texts. The Dead Sea Scrolls make it abundantly clear that both modes of transmission were practiced during copying acts in the Second Temple period, and it would be simplistic to insist on an either/or answer. Whether we think of separate scribal schools characterized by different approaches or occasional functional differences within the same scribal community, we must reckon with the reality that scribes sometimes replicated their exemplars and at other times altered them. It is difficult to say which mode of transmission was the most common. As so many of the Dead Sea Scrolls reflect intentional editorial interventions in their texts, it is tempting to view such interventions as the norm. However, this is not necessarily so for at least four reasons.

First, apart from relatively minor editorial corrections or emendations, there is virtually no material evidence for such intentional changes in any of the Dead Sea Scrolls. The vast majority of editorial changes we discuss in light of the Dead Sea Scrolls actually took place prior to the copying of the scrolls which actually attest to the changes, whereas the scrolls themselves give little material evidence of an interventionist scribal approach.

Second, the consistently high percentages of verbatim agreement between all of our textual witnesses would be completely impossible in a scribal context with little regard for precise replication of exemplars.

Third, the unknown (and probably large) number of texts genealogically intervening between most of our extant witnesses further requires a generally conservative copying approach. That is, if two manuscripts copied from a common ancestor are very close to each other, this not only implies that they were copied conservatively, but also that each intermediate stage between them and that common ancestor was also copied in a like manner.

Fourth, even when clear editorial interventions are made, these typically affect only a small proportion of the text, and the scribes who made these changes still copied the majority of their materials directly from their exemplars.

For these reasons, the default copying procedure for most copying acts in the late Second Temple period was arguably accurate (and usually fairly precise) replication of the exemplar, with occasional editorial interventions for specific purposes. Every text reflects the result of mixed treatment in the course of its transmission. Thus, literary critics are not on safe ground to work only with the text of Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS) as a starting point. Rather, there is a need to interact carefully with all the manuscript evidence to first understand the documented stages of textual development.

The reasons why these different conservative and interventionist approaches were practiced are difficult to determine. Most likely they are related to perceptive scribes, balancing the needs to preserve, update, interpret, and harmonize the text. In this process certain broad observations are generally true. For example, text was rarely (intentionally) omitted and the content and structure of the text was relatively infrequently rearranged. Yet textual traditions tended to grow over time, primarily on account of materials added or altered on the basis of an interpretation deemed already implicit in the text or explicit in parallels elsewhere in the Pentateuch. In other words, except for the so-called “Reworked” Pentateuch (4Q158, 4Q364–367), very little of the documented pluriformity in the pentateuchal tradition actually reflects the creative intent of an innovative scribe. Scribes in the late Second Temple period were attempting to faithfully transmit (and sometimes further develop) received traditions, but they were not free to substantially contradict them or alter them for explicitly partisan purposes. We can only presume that many of these tendencies were active also in earlier, undocumented stages, which has important ramifications for literary criticism and reception history.

Updating, Interpreting, and Harmonizing within the Dead Sea Scrolls

Let us focus more on the updating, interpreting, and harmonizing tendencies in the tradition. Impulses to update and interpret the text tend to occur sporadically and incrementally in the documented textual tradition. It is rare that these can be synchronized into something that one might call a “redactional layer.” We can at times document early interpretive glosses, such as the phrase “And Joseph was in Egypt,” which is found at the beginning of Exodus 1:5 in the Septuagint and at the end of the verse in almost all of our Hebrew witnesses, but is lacking in 4QExodusb. Presumably in this case the interpretive marginal comment of an ancestor of the Septuagint and most of our Hebrew tradition was at some point interpolated into the text. 4QExodusb was either independent of this common ancestor or escaped the interpolation. It is probable that many such occasional changes occurred after the last undocumented “redactional layer” hypothesized by redaction critics, but before our extant textual tradition split, greatly complicating any attempts to find coherent patterns in the literary critical data.

Even more pervasive is the widespread harmonistic impulse evident in the tradition. Every substantially-preserved pentateuchal text reflects both unconscious and conscious harmonizations—not even the Masoretic text and its predecessors have escaped this tendency. In the transmission of the Pentateuch in the Second Temple period, there was an unmistakable sense that the text must be internally coherent, its discrepancies resolved, and at times, tensions alleviated between commands and their fulfillment or between parallel stories (e.g., the so-called “pre-Samaritan” expansions). For instance, in Exodus 1:5, 4QGenesis-Exodusa, 4QExodusb, and the Septuagint say that Jacob had 75 descendants, instead of the 70 of the Masoretic and Samaritan traditions. This appears to be a harmonization to a similar calculation in some witnesses to Genesis 46:27, based on a version of Genesis 46 that has in turn already been supplemented with genealogical information from Numbers 26:28-37. The two Qumran manuscripts add the extra numeral “five” in different positions, betraying the fact that this same harmonization was made more than once in the tradition. Literary critics must, therefore, reckon with two realities: (1) the earliest text recoverable by comparison of documented texts is probably already a harmonized text and (2) the harmonistic impulse pervaded scribal thinking already in the late Persian and Hellenistic periods and undoubtedly affected any editorial development during these periods or immediately prior.

Literary Traditions in the Dead Sea Scrolls

Finally, we must also briefly broach the controversial issue of the boundaries of literary traditions. The Dead Sea Scrolls have greatly problematized simplistic distinctions between closely related literary works. In many cases it is difficult to determine when an edited version of a text retains its identity as a revised copy of the work, or when it takes on a life of its own as a separate, derivative work. A literary distinction between most “rewritten scripture” texts and their scriptural base texts is clear enough based on their selective use of their bases texts and major structural and content differences. I think such a distinction would have been (and indeed sometimes explicitly was) recognized by authors, scribes, and readers in antiquity. There are, however, borderline cases that are not so easily discerned (e.g., the “Reworked” Pentateuch manuscripts from Qumran), especially due to their fragmentary preservation. In the end, there is little doubt that the question of literary identity and the limits of literary traditions in the Second Temple period has been complicated by the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls and will be a fruitful avenue for future investigation.

Many have discussed the significant editorial differences evident in the Dead Sea Scrolls, and the pluriformity of the texts of the Hebrew Scriptures in the Second Temple period is now common knowledge. The differentiated state of the tradition already in the third century BCE (compare, for example, the “pre-Samaritan” 4QExodus-Leviticus and the Septuagint) suggests that many of the major differences between pentateuchal witnesses were created already in the fourth century or even earlier. Yet, these documented editorial changes still reflect typologically late developments on a much more restricted scale than those typically suggested by source and redaction critics. These latter stages of the development of the text of the Pentateuch are—and will probably always remain—undocumented hypotheses. Nevertheless, it is clear that the Dead Sea Scrolls provide a limited window into the patterns of text production that can be expected in the Persian period, and literary critics cannot afford to ignore these lessons.

Further Reading on Topics and Texts Treated in this Article

M. Segal, “The Text of the Hebrew Bible in Light of the Dead Sea Scrolls,” Materia Giudaica 12 (2007): 5–20.

E. Tov, Scribal Practices and Approaches Reflected in the Texts Found in the Judean Desert, STDJ 54 (Leiden: Brill, 2004).

E. Ulrich, The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Developmental Composition of the Bible, VTSup 169 (Leiden: Brill, 2015).

S. White Crawford, Rewriting Scripture in Second Temple Times (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2008).

Drew Longacre is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Groningen for the project “The Hands that Wrote the Bible: Digital Palaeography and Scribal Culture of the Dead Sea Scrolls.” His University of Birmingham doctoral dissertation examined the Exodus manuscripts from the Judean Desert and their interrelationships.

The Ancient Jew Review and Trinity Western University Dead Sea Scrolls Institute forums and reviews commemorating the 70th anniversary of the discovery of the Qumran scrolls were edited by Dr. Andrew Perrin (Trinity Western University), Dr. Andrew Krause (University of Münster), Dr. Jessica Keady (University of Chester), and Spencer Jones (Trinity Western University).

For news, events, and research opportunities at the Trinity Western University Dead Sea Scrolls Institute follow Twitter.com/twudssi and Facebook.com/twudssi.