Qumran’s Glimpses into Textual Evolution

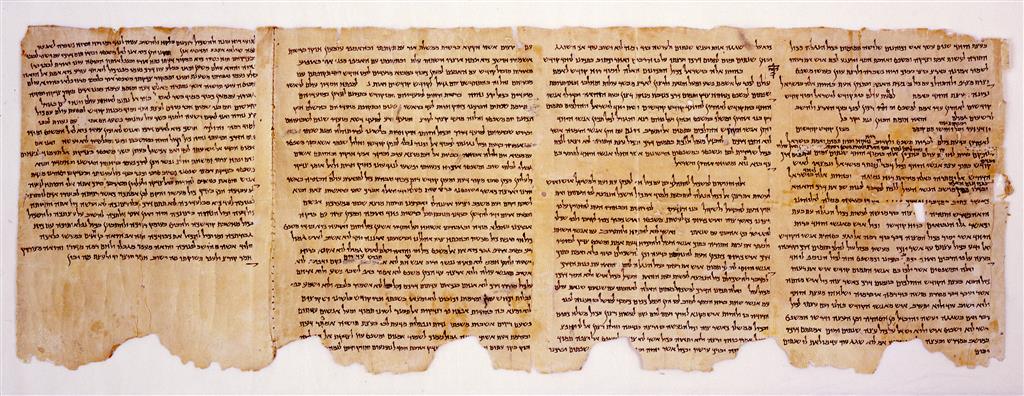

One of the most fascinating insights provided by the Dead Sea Scrolls is the way they allow us a first-hand glance at the way in which ancient texts grew. By looking at the original manuscripts we are almost watching ancient texts grow and evolve in front of our eyes. The question of how ancient texts developed over time has been and continues to be of great interest to scholars of the Hebrew Bible. The important difference for Qumran studies is that we have actual ancient manuscripts to check the theory in crucial places.

The extraordinary circumstances of the discovery of the scrolls are arguably an immense bonus, as well as a significant challenge. They are a benefit because we have texts that were found in situ, in the very place where their ancient owners left them. Many of these ancient manuscripts go back to a time not very far removed from the date of their composition. The context of the discovery also posed considerable difficulties because it suggested initially that the material was more coherent and unified than it turned out to be on closer inspection.

One revealing perspective gained from studying the manuscripts is their testimony to some very complex literary developments and interrelationships between texts. Qumran studies started off with the assumption that, given the antiquity of the manuscripts, we need not expect the same level of complex literary growth that is frequently argued for with reference to the composition of biblical texts. Scholars of the non-biblical scrolls include those sensitive to unevenness and differences between and within texts—the splitters. Then there are others who have a profound dislike of cutting up a perfectly good text—the clumpers. The interesting thing is that the ancient copies of the Community Rule have added some spice to this debate. Here we have hard and fast manuscript evidence that the kind of thing splitters love actually happened in antiquity. The manuscripts of the Community Rule provide scholars with one of the most fertile pieces of evidence for the gradual growth of an ancient text.

The Community Rule Manuscripts

Qumran revealed twelve at times quite different manuscripts of this work, which were composed, copied, and revised over the greater part of two hundred years (ca. 125 BCE–50 CE). Whereas the primary evidence tells a story of textual growth and change, scholars have traced the developments behind this evidence in radically different ways. The table below lays out one of the most talked about examples with the differences highlighted in italics.

The obvious focal points of the debate have tended to be differences between manuscripts, with disagreement and discussion often centered on the question of which manuscript has preserved the earlier stage in the growth of the text. A great deal of discussion has been devoted to the question of whether or not the longer 1QS text, which underscores the role of the sons of Zadok, presupposes the shorter 4QS tradition that allots a prominent place to the many. While agreeing with those scholars who argue the longer 1QS text elaborates the shorter 4QS tradition, I have emphasized the importance of significant overlap between the manuscripts alongside the differences. I suggested that the earliest form of the text is to be found in the shared material. Such shared textual traditions are likely to go back to a time before the differences that now catch our attention, had emerged. This is best illustrated by looking at the same text again, but this time with the overlap highlighted rather than the differences.

The best hypothesis on how these texts evolved seems to me one that accounts for both differences and overlaps between the manuscripts. Being in the possession of multiple copies of ancient manuscripts allows us to see the texts evolve in front of our eyes not only in one and the same manuscript, where the original or a subsequent scribe might add some words, but also in the differences and overlaps between manuscripts of the same composition.

Our manuscript evidence—particularly that of the Community Rule—points in the direction of a complex evolution of texts. Source and redaction criticism provide the tools to investigate the growth spurts and adjustments of textual development in all its complexities. In most cases, its conclusions depend solely on the quality of the arguments and the insights of the interpreter with little chance of proof or consensus. With the manuscripts of the Dead Sea Scrolls, especially those of the Community Rule, we are in the privileged position to be able to trace their textual evolution first hand. Disagreements are likely to remain, however, when it comes to hypotheses on the direction of the developments we witness.

Charlotte Hempel is Professor of Hebrew Bible and Second Temple Judaism at the University of Birmingham. The current Executive Editor of Dead Sea Discoveries, her publications in Qumran studies include The Qumran Rule Texts in Context: Collected Studies (Mohr Siebeck, 2013) and The Damascus Texts (Sheffield Academic/Bloomsbury, 2000).

Further Reading on Topics and Texts Treated in this Article

C. Hempel, The Qumran Rule Texts in Context: Collected Studies (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2013).

S. Metso, The Serekh Texts (London: T & T Clark), 2007).

A. Schofield. From Qumran to the Yahad: A New Paradigm of Textual Development for the Community Rule (Leiden: Brill, 2009).

The Ancient Jew Review and Trinity Western University Dead Sea Scrolls Institute forums and reviews commemorating the 70th anniversary of the discovery of the Qumran scrolls were edited by Dr. Andrew Perrin (Trinity Western University), Dr. Andrew Krause (University of Münster), Dr. Jessica Keady (University of Chester), and Spencer Jones (Trinity Western University).

For news, events, and research opportunities at the Trinity Western University Dead Sea Scrolls Institute follow Twitter.com/twudssi and Facebook.com/twudssi.