The Shaping and Shapes of Ancient Texts at Qumran

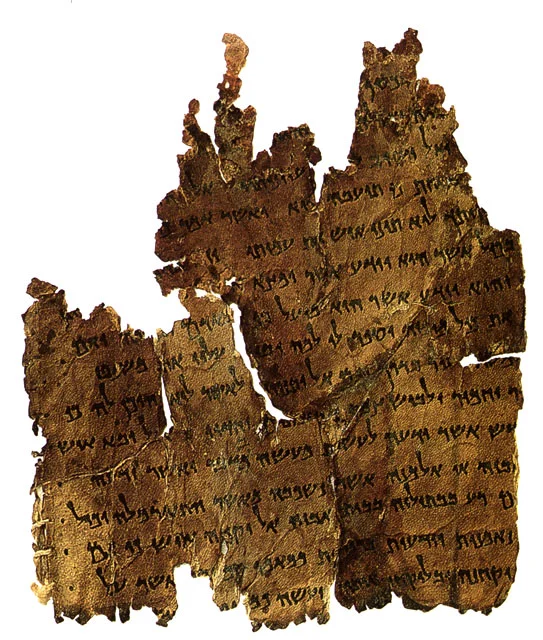

What is an ancient text? How should similar but different texts be treated? When should a text be considered a “recension,” and when is it an independent text? How do such closely-related texts clarify each other? These general questions concerning the transmission of texts and traditions are relevant, sometimes crucial, for the study of the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament, and rabbinic literature. The answers are complex and elusive. The growth of texts is one of the most important phenomena for understanding the form in which they reached us. The texts found at Qumran help clarify various aspects of the growth of many ancient religious writings, because they represent a variety of texts from a period (ca. second century BCE–first century CE) from which previously no texts written in Hebrew had been preserved (with the exception of Ben Sira and the Damascus Document, see below).

The biblical texts discovered at Qumran demonstrate the conservative state of the textual transmission of the Bible. Some scrolls are remarkably similar to the Masoretic text (known from medieval copies), the Samaritan Pentateuch (known from very late manuscripts), and the Hebrew text underlying the Greek Septuagint. On the other hand, the texts found at Qumran also manifest that the textual range of biblical books was more complex than what one could imagine before this discovery. In the case of some texts found at Qumran it is not easy to define whether they are indeed biblical or texts rewriting the Bible, or, for that matter, what is meant by “biblical.” This is the case, for instance, in the so-called “Reworked Pentateuch.” While by and large it closely related to other biblical texts, there are passages that clearly display the growth of the text. The exegetical element is frequently the cause of the expansions in these texts (4Q364 3 ii: A dialogue between Isaac and Rebecca, similar to Jub. 27:14–18; 4Q365 6 ii 1–7: adding an apocryphal song of Miriam to the song of Moses at the sea).

The much expanded text in the Septuagint version of Esther shares quite a few features with the expansions in "rewritten Bible" Qumran scrolls (whether the rewriting was done in the Hebrew text or by the translator). For instance, expansions C and D add Mordechai’s prayer and Esther's prayer (Esther 4:17), explain her abstinence from “wine of libation” and her abhor to “the bed of the uncircumcised” and reports that Esther took with her two of her attendants when she went to see the King (Esther 5:1) because these attendants are mentioned as fasting with Esther in Esther 4:16. The Septuagint text of Esther demonstrates that similar growth of texts took place in wide circles during the Second Temple period.

Variant Passages and Fluidity of the Damascus Document

A pair of eleventh century manuscripts of the Damascus Document (or Damascus Covenant), composed in the second–first centuries BCE were revealed in the Cairo Genizah: one copy (manuscript A) contains much more text than the other (manuscript B). Where the two manuscripts do overlap, there is a substantial discrepancy between them in one long passage, although the sections framing this passage is the same in both manuscripts.

Scholars agree that the material in both manuscripts was composed in the Second Temple period. Opinions differ, however, concerning the relationship between the two manuscripts. While some scholars maintain that the manuscripts contain a different recension of the passage or (possibly) of the entire work, others suggest that the dissimilarity was caused by a textual mishap. I have tried to demonstrate the former view, suggesting that the two recensions emerged due to differing interpretations of the Hebrew root mlṭ (meaning either “to be saved” or “to flee”). These observations are significant for assessing the complex relationship between the one and the many, that is, between the one work and its various recensions, and the freedom to reshape passages in the transmission history of a work in a relatively short time period.

Further Fluidity of “Non-Biblical” Texts in the Qumran Collection

As seen here with Damascus Document, several other scrolls attested at Qumran illustrate the fluidity of non-biblical texts in the late Second Temple period. For example, an apocryphal (“autobiographical”) psalm of David, Psalm 151, was known for generations of scholars from the Septuagint. This psalm, however, was also included in 11QPsa, in a different, more detailed form. Again, the relationship between the two versions of the psalm is a matter of scholarly debate, but the fluidity of the text is a fact. Instances such as this make us aware of how the multiform recensions of the text should change our attitude to texts in general and the interpretive issues they attend to. Instead of envisaging a single fixed text that has to be interpreted (which was the modus operandi prior to this discovery), we must now engage ourselves with multiple texts, varying from each other.

A second example may be found in another text central to the life and thought of the Qumran group, the Serekh ha-Yahad. Initially only a single copy of this work was known, the well-preserved copy of Qumran cave one (1QS), and consequently the text of this copy was equated in scholarship for a few decades with the work Serekh ha-Yahad. The publication of the scrolls from cave four proved that the situation is more complex. One copy of the Serekh (4QSd) does not include the first four columns of 1QS; another copy (4QSe) does not include the hymn at the end of 1QS (columns 10–11), and instead includes calendric material; and still another long passage of the cave one manuscript (1QS 8:15–9:11) is lacking entirely in 4QSe. These facts by themselves demonstrate that “the Serekh” is in fact a compilation of works differently shaped in various copies. All of these are – on a different level – the result of compiling earlier sources of community rules of various groups of the same movement.

The best example for the fluidity of textual transmission of the Serekh is the beginning of 1QS column 5:

Even a quick look at this comparison reveals the variety between the two versions.

It is noteworthy in this context how the phrase ‘for lawsuit and judgment’ (lacking in 4QSd) probably describe the tasks of the Community’s member, described in 1QSa 1:13–14 (cf. 1QS 6:22, 7:21). The following words included only in 1QS, “to proclaim as guilty those who trespass the law,” seem to interpret this “judgment” as the eschatological judgment of the sinners by the members of the community (cf. 1QS 8:6-10). The meaning of the sentence has been dramatically changed by the growth of the text.

The Evolution of Formulae and the Transference of Passages between Compositions

Thus far I have dealt with textual variant readings of the same work. Two other phenomena, however, should be mentioned regarding the similarity of content and phraseology between some community documents. It should be stressed here that each of these phenomena represents dimensions of the growth of texts different than those discussed above.

First, some consideration needs to be made of the close relationship between passages in different works. For instance, several rules in Damascus Document are similar to rules in the Serekh. Careful philological comparison of the two texts reveals the dynamics of the text and between texts. Instead of treating the text as a static entity, we are sometimes fortunate enough to see it rapidly evolving, within a short period of time, at times at a margin as small as a few decades. To my mind, studying the relationship of parallels in the Qumran scrolls and rabbinic literature may benefit also the study of the traditions in the synoptic Gospels.

The phenomenon involves the evolution of formulae. For instance, catchphrases that are repeated in Serekh ha-Yahad are sometimes unintelligible in their present form, but can be properly interpreted when seen in the light of other occurrences. This is another aspect of the dynamics of texts, on a different level. For instance, the passage of 1QS 8:1-4 is an elaboration of the formula in Jubilees 36:3-4:

To enact truth, righteousness, justice, love of kindness and modesty (?) each one to (or: with) his neighbor, keep faith on the earth with steadfast mind… (1QS 8:1-4)

I am commanding this, my sons, that you might enact righteousness and uprightness upon the earth… Love your brothers as a man loves himself… acting together on the earth, and loving each other as themselves (Jubilees 36:3).

The phrase “on the earth” can scarcely be explained in the present text of the Serekh, but once it is realized that another formula (“to enact truth and righteousness on the earth”) is elaborated here, this phrase can be easily explained. The phrase “to keep faith with steadfast heart” is borrowed from Isa 26:2–3, and it precedes and follows the words “on the earth.” Being aware of the growth of formulaic phrasing in texts is most important for their interpretation and can serve as a key to unlocking their interrelationship and growth.

Conclusion and Afterword

The many texts, biblical and non-biblical, discovered at Qumran open our eyes to see the multiple faces and the multiple phases of texts. Their fluidity is a fact that demands an explanation, and the explanation will continue to be debated (probably there is no one explanation for all the expanded texts). Yet, seeing the textual dynamics is most significant for treating phenomena in the Old and New Testaments. It is also instructive to compare the transmission of texts at Qumran with the transmission of rabbinic texts (both on the purely textual level and on the level of parallel passages). Having multiple forms of one text (either in various forms of the same work or in parallels) is typical for the works in the rabbinic corpus, most of which were orally transmitted for a long time (unlike the Dead Sea scrolls). The earliest manuscripts of rabbinic works are usually not older than the tenth century. With all due reservations, the transmission of texts in the two corpora is mutually illuminating.

Further Reading on Topics and Texts Treated in this Article (in sequence of article)

E. Tov, “Reflections on the Many Forms of Hebrew Scripture in Light of the LXX and 4QReworked Pentateuch,” in From Qumran to Aleppo, edited by A. Lange et al. (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2009), 11–28.

E. Tov, “Three Strange Books of the LXX: 1 Kings, Esther, and Daniel Compared with Similar Rewritten Compositions from Qumran and Elsewhere,” in Die Septuaginta: Texte, Contexte, Lebenswelten, edited by M. Karrer and W. Kraus (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2008), 379–384.

M. Kister, “The Development of the Early Recensions of the Damascus Document,” Dead Sea Discoveries 14 (2007): 61–76.

M. Segal, “The Literary Development of Psalm 151,” Textus 21 (2002): 139–158.

M. Kister, “4Q392 and the Conception of Light in Qumran ‘Dualism,’” Meghillot 3 (2005): 140–142 (Hebrew).

C. Hempel, “The Literary Development of the S Tradition,” Revue de Qumran 22 (2006): 389–401.

J. Licht, The Rule Scroll (Jerusalem: Bialik Institute, 1965), 168–175, 187 (Hebrew).

M. Kister, “Commentary to 4Q298,” Jewish Quarterly Review 85 (1994): 245–249.

Translation used: F. García Martínez and E. J. C. Tigchelaar, The Dead Sea Scrolls Study Edition (Leiden: Brill, 1998).

Menahem Kister is J. L. Magness Professor of Bible at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His many publications in Dead Sea Scrolls texts and traditions include The Qumran Scrolls and their World (Yad Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, 2009) and “Some Observations on Vocabulary and Style in the Dead Sea Scrolls” in Diggers at the Well (Brill 2000).

The Ancient Jew Review and Trinity Western University Dead Sea Scrolls Institute forums and reviews commemorating the 70th anniversary of the discovery of the Qumran scrolls were edited by Dr. Andrew Perrin (Trinity Western University), Dr. Andrew Krause (University of Münster), Dr. Jessica Keady (University of Chester), and Spencer Jones (Trinity Western University).

For news, events, and research opportunities at the Trinity Western University Dead Sea Scrolls Institute follow Twitter.com/twudssi and Facebook.com/twudssi.