“As an occasional series, Unexpected Influences asks scholars to reflect upon one book outside their respective fields that influenced their scholarship.”

Dr. Beth Berkowitz

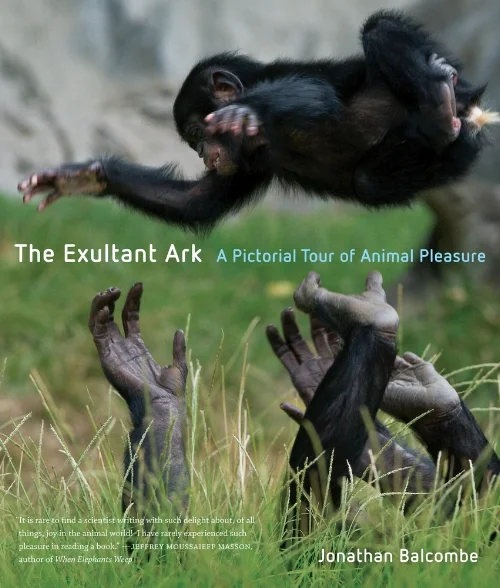

The book jacket shows a baby bonobo suspended in the air, arms akimbo, having just been tossed up by her mother, who lies hidden, except for hands and feet, in the tall grass below. It is a vision of unadulterated joy, the kind we know as a child when we are thrown up into the air or tickled.

How many books give you a jolt of pleasure when you read them? The Exultant Ark: A Pictorial Tour of Animal Pleasure, by Jonathan Balcombe, does that. Call Balcombe’s book pornography without the sex, though sex is in there too, along with chapters on play, touch, comfort, food, and friendship. It qualifies as a coffee-table book, with its glossy pages and professional photography, but it is also a serious inquiry into how other species experience pleasure.

I was studying the Babylonian Talmud’s commentary on the requirement for animals to rest on the Sabbath (“…you shall not do any work--you, your son or daughter, your male or female slave, or your cattle…” Exodus 20:10). I wanted to write about animal religion, inspired by Donovan Schaefer’s Religious Affects. The interest of the rabbinic texts was the prohibition against carrying “burdens” on the Sabbath, and the texts wanted to know which animal accessories (saddles, bridles, etc.) count as burdens and which do not. The Talmud contrasted accessories designed for restraint or work with ones the animal wears for adornment, comfort, or pleasure. I found myself in the midst of a discussion of animal oils, ointments, and warming cloths. Who knew that the Talmud talked about sheep massages? I began to look for research on animal pleasure, and that’s when I came across Balcombe’s book.

It is not often that my work requires pleasure. Balcombe’s book, which I keep displayed on my shelf, reminds me that all of us are pleasure-seeking animals.

Beth A. Berkowitz is Ingeborg Rennert Associate Professor of Jewish Studies in the Department of Religion at Barnard College.

Dr. Ishay Rosen-Zvi

Since I had been asked to venture beyond my Talmudic comfort zone, I would like to talk about Yair Horowitz, a forgotten, modernistic poet, born and raised in Tel-Aviv. His poems combine grandiose spiritualism with plain carnality and this-worldliness; a permanent feeling of transience and a continuous presence of death (he suffered from heart problems since childhood, and died in 1988 at the age of 47). Of all his poems one constantly accompanies, nay, guides me, academically and otherwise. It is from the 1976 collection "while siting alone (בשבתי לבדי)" and its title is קרובים אל קסם מוטב שנדע ("being or getting near magic, we should better know" [or learn or discern]. I will not even try to offer a translation of more than that, and I actually suspect that there are no translations to any of Horowitz's magical poems). It’s a very long poem, suggestively repeating this single phrase מוטב שנדע. It is at the same time utterly mystical and fully naturalistic. It moves from the wind, cloud, and lights to stairs, wheels and sheets; from the grand marble palaces to the longing body; all equally immersed with a feeling of temporariness and urgency. "we should better know," "before it gets dark, we should better know." But instead of this impermanence being translated into helplessness, it appear as a keen, fervent passion to know, to learn, to see, to absorb, to understand. I have used one line from this grand poem as a lemma to my article on the genealogy of the concept of the goy: "we will know the dissecting knife (נבין את הסכין המבדיל)." But it is the whole poem, with its never-ending yearning for knowing, the urgency of learning, the pleasure and frustration (and inherent failure) bound with it, that nourishes me, in many different ways, whenever I study or write.

Ishay Rosen-Zvi is Associate Professor of Hebrew Culture at Tel Aviv University, where he serves as the head of the Talmud and late antiquity section.