How do we envision this or that personage from Late Antiquity? What we know of their extant works and the works attributed to them will guide, consciously or not, how we form a picture of them. Two books (by Young Richard Kim and Andrew Jacobs) have recently appeared on the fourth-century writer and bishop, Epiphanius. The 2016 annual meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature featured a review panel of these monographs, and these responses were recently published on AJR. Reading these pieces I was inspired to compose a brief addendum to highlight something about Epiphanius that is all too easily forgotten: the authorial identity of “Epiphanius” extended beyond the Greek-speaking world and the works of his own pen. The numerous translations of the Epiphanian corpus into several languages of Late Antiquity reveal just how well-known and highly regarded the name of Epiphanius was across Christian language-communities, and this fact can further fill in our picture of the function of this textual “Epiphanius.”

The expansion and eventual growth of Christianity across the centuries of Late Antiquity in the eastern Mediterranean offers students and other interested researchers a “formidable battery of languages” in the form of textual evidence.[i] As Christianity swelled north into the Caucasus, south into Africa, and east into Central Asia, through translations from Greek, and eventually from other languages, an extensive range of literary texts migrated across the multilingual expanse of Christian presence. The result is that for many of these texts we have two, three, and even more versions. The surviving products of this translation enterprise are a potential playground for philologists and other scholars. We might compare Buddhism[ii] and Manichaeism[iii] for other examples of a linguistic spread within the development of a religious movement: for Buddhism, Pali, Sanskrit, Chinese, Tibetan, Japanese, Old Uyghur, and Tangut; for Manichaeism, Syriac, Middle Persian, Parthian, Coptic, Sogdian, Bactrian, Chinese, and Old Uyghur. In some cases, the spread of Christianity through major instances of conversion even entailed the creation of new writing systems, as in the cases of Armenian, Georgian, and Glagolitic.

Each of the works in the alphabet soup of bibliographic guides to textual Late Antiquity — such as CANT (Clavis Apocryphorum Novi Testamenti), BHO (Bibliotheca Hagiographica Orientalis), BHG (Bibliotheca Hagiographica Graeca), and BHL (Bibliotheca Hagiographica Latina) — serves a particular purpose. The multi-volume CPG (Corpus Patrum Graecorum) lists references to the full catalog of works attributed — those considered spurious are so indicated — to church fathers who were known or assumed to have written in Greek (including, of course, Epiphanius). Each work has a unique identifying number, so that one can simply refer to a work by its CPG identifier.[iv] Significantly, these references include texts that were translated into other languages, and also texts that may never have existed in Greek at all, but only, for example, in a Coptic or a Syriac version. Further, these references sometimes indicate published editions and/or modern translations; occasionally, however, references merely point to some kind of evidence that this or that work exists such as a note in a manuscript catalog. Thus, texts published and unpublished are almost comprehensively represented in the bibliographic list. (It is unfortunate that many would-be users should be barred from such a useful and often-referenced resource by price or by the distance or inconvenience of libraries.) Some fathers, notably John Chrysostom and Ephrem (“Graecus”), may have an especially long list of attributed works in these languages (some with a Greek Vorlage, some not). Epiphanius, too, can justifiably join their ranks.

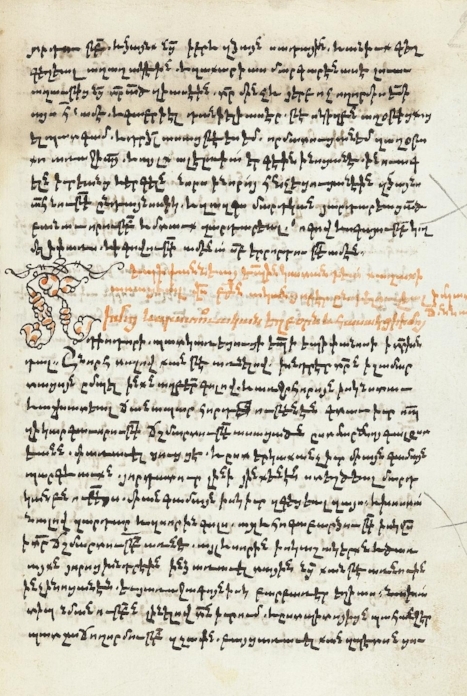

I first realized how important the extra-Greek survivals of Epiphanian texts were when I encountered his On Weights and Measures (CPG 3746), in particular, his report at the beginning about the mythic seventy-two translators of the Hebrew Bible into Greek in Egypt. This work survives in full only in Syriac. Sometime thereafter I had occasion to read part of his On the Gems in Aaron’s Breastplate (CPG 3748), fully extant only in Georgian, but with parts also in Greek, Armenian, (Sahidic) Coptic, Arabic, and Latin. This Georgian version was translated from Armenian, which, it seems, was based on a (lost) Syriac translation.[v] Because no substantial amount of either of these texts survive in Greek, we cannot say very much definitive about differences from the Greek in these versions or fragments thereof.

In CPG, texts attributed to Epiphanius are covered in vol. 2, nos. 3744-3807 (with those considered spurious beginning at no. 3765), and in the Suppl. volume, pp. 207-219. The titles of these works, those considered genuine as well as spurious, are listed below along with the languages in which at least something of each work has been found.[vi] Following this list I have included some manuscript details drawn from the work of catalogers from the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library (HMML), which partially overlap with the CPG material.

When we think about the frequency of translation for certain texts or parts thereof, the homilies immediately come to mind, but in particular, both in the CPG catalog and among the manuscripts from HMML cited below, we may note the especial popularity of the (spurious) Homily on Jesus’ Burial (CPG 3768), available in Syriac, Arabic/Garšūnī, Coptic, Armenian, Georgian, Old Church Slavonic, as well as Greek.[vii] As mentioned above, at least parts of On the Gems circulated in more than one language, and the same may be said about the (again spurious) little texts on the prophets, apostles, and disciples (CPG 3777-3782).

How did these translators and readers regard “Epiphanius”? When considered cross-linguistically in this corpus, the author with this name (i.e. whether genuine or not) appears as a versatile writer with broad knowledge. He can deal with and explain the significance of realia of parts of the Bible, as in On Weights and Measures and On the Gems. He can, like a collector (but not a dispassionate one), list and discuss heresies (in the Panarion) or details of the distinguished among biblical heroes (in the catalogs of prophets, etc.). And he is a homilist, with collections or individual pieces across more than one language. In Arabic and Gǝʿǝz he is concerned with interpreting the beginning of Genesis (Hexaemeron), and his name is even associated with the widely popular collection of Christian interpretations of the natural world, the Physiologus! There seems to be no real pattern of specific interest for Epiphanian translations in these languages.

Thanks to the two aforementioned books and the AJR essays, we now know much more about how Epiphanius, or at least a constructed Epiphanius, has fared in his legacy. I would like to highlight a voice in this evaluation from around eighty years ago (1935), if for no other reason than the memorable formulation of the judgment about Epiphanius as an author. The editor (or rather, facsimile-publisher) and translator of the Syriac version of On Weights and Measures was “a diligent and careful southerner” James Dean (no, not that one!). His senior colleague at the Oriental Institute (Chicago) was Martin Sprengling, who offered a foreword to Dean’s book, with the following about Epiphanian texts:

We soon found that editing any Epiphanius text was no joke, least of all in a Syriac translation for much of which the original Greek is missing. Piecing together the oddments of information and misinformation which he considers knowledge, sorting them, getting at the meaning of his sloppy style of expression, is often much like attempting to create order out of chaos; it demands heavenly patience and superhuman, perhaps super divine, ingenuity. (p. ix)

Whatever we might say about the perspicuity or style of texts attributed to Epiphanius — that is, whether we would agree with Sprengling or not — we can easily recognize that “Epiphanius”, and a great many other writers listed in the pages of CPG, requires notice of several language-traditions beyond Greek.

These extra-Greek survivals of Epiphanian texts underscore the important place of, at a minimum, an awareness of these other languages and the activity of translators, and at best, facility in reading and understanding one or more of these languages. They remind us likewise of how far, linguistically speaking at least, the name and fame of Epiphanius had spread, and much the same might be found for many other writers included in the pages of CPG. The state of early (and later than “early”) Christian studies is hardly to the point yet where it can do without frequent reminders that Greek and Latin have no monopoly in the study of Christianity. I hope that highlighting this multilingual witness to the writings of Epiphanius and the pseudo-Epiphanii might go some way toward encouraging further work on this corpus of writing, apparently considered important by readers, translators, and scribes of Late Antiquity, to build on the research and analysis evinced in the aforementioned books and AJR essays.

****************************

From CPG (vol. 2) 3744-3807 (with Spuria beginning at 3765); also see the Suppl. volume, pp. 207-219

3744 Ancoratus

Greek, Coptic, Arabic

3744 Suppl.

Coptic, Armenian (fragm.), Gǝʿǝz, Arabic and Gǝʿǝz (fragments)

3745 Panarion

Greek, Arabic, Georgian

3745 Suppl.

Georgian

3746 On Weights and Measures

Greek (incomplete), Syriac (complete), Latin (fragment)

3746 Suppl.

Georgian, Armenian (fragments)

3748 On the Gems in Aaron’s Breastplate

Georgian (complete), Armenian (fragments), (Sahidic) Coptic (fragments), Arabic (fragment), Greek (epitome), Latin (epitome)

3748 Suppl.

Armenian (Epitome), Coptic, Arabic and Gǝʿǝz (fragment), OCS

3750 Suppl. Epistle to Theodosius

Syriac (fragment)

3754 Epistle to John of Jerusalem

Latin, Greek (fragment)

3754 Suppl.

Greek (fragments)

3758 Epistle to the Elders of Pisidia

Syriac (fragment in Severus of Antioch)

3759 Epistle to Basilianus

Syriac (fragment in Severus of Antioch)

3760 Epistle to Magnus (= Ancoratus 77)

Syriac (fragment in Severus of Antioch)

SPURIA

3765 Anakephalaiosis (different recensions)

Greek, Armenian

3765 Suppl.

Syriac, Gǝʿǝz (fragment)

3766 Physiologus

Greek

3766 Suppl.

Latin, Syriac, Armenian, Coptic (fragments), Arabic, Gǝʿǝz, Georgian, Old Church Slavonic

3767 Hom. for the Feast of Palms

Greek, Arabic

3767 Suppl.

Arabic

3768 Hom. on the Burial of the Divine Body

Greek, Syriac, Coptic, Armenian, Georgian, Arabic, Old Church Slavonic

3768 Suppl.

Coptic, Armenian, Arabic, Old Church Slavonic

3771 Hom. in Praise of Mary

Greek, Coptic, Syriac, Armenian, Arabic, “Old Russian” [= ?]

3771 Suppl.

Coptic, Syriac, Armenian, Arabic

3774 Hom. for Hypapante/Candlemas

Greek, Syriac

3777 On the Life and Death of the Prophets (earlier recension)

Greek, Syriac

3777 Suppl.

Latin, Syriac, Armenian, Arabic, Gǝʿǝz, Old Church Slavonic

3778 On the Life and Death of the Prophets (later recension)

Greek, Georgian

3779-3782 Names and Lists of Prophets, Apostles, and Disciples

Greek

3779 Suppl.

OCS, Latin, Georgian, Armenian, Syriac

3783 Hexaemeron

Arabic, Gǝʿǝz

3784 Comm. on the Psalms

Armenian, Georgian

3785 Comm. on Luke

Armenian

3787 Notitiae episcopatuum

Greek, Armenian

3788 Apophthegmata

Greek, Arabic, Georgian

3792 Suppl. Hom. on the Antichrist

Armenian

3793 Suppl. (a) Oration on the Edessene Image

Armenian

3793 Suppl. (b) Homilies

Armenian [Vind. Mechit. 11, a 19th-cent. copy of a 1350 manuscript, has 40 homilies attributed to Epiphanius]

3797 Anaphora graeca (fragm.)

[apparently translated from Armenian into Greek, but attr. to Epiphanius; on the addition of water to the eucharistic wine]

3798 Anaphora aethiopica

Gǝʿǝz

3800 Hom. on Mary

Georgian [perh. also Syriac]

3801 Hom. on the Conception of Anna

Georgian

3802 Suppl. Hom. on the Birth of Christ

Coptic (fragment)

3803 On Epiphany

Coptic

3803 Suppl.

Coptic

3805 Homilies; Treatise against the Jews

Arabic

3807 Arabic fragments

*************************************

From HMML (see there for the collection abbreviations used below)

Syriac

On Weights and Measures, epitome

CCM 22, ff. 152v-153r

Extract from a Homily on the Burial of Jesus (Sauget in Orientalia Christiana Periodica 27 (1961): 420, mentions another Syriac manuscript, but that seems to be a different fragment.)

MGMT 33, pp. 1-8; SOAH 16, pp. 537-40

Garšūnī

Homily on the Burial of Jesus (based on the incipits, there is some variation among these Arabic witnesses.)ASOM 124, ff.81v-86v; CCM 345, ff. 34v-44r; CFMM 286, pp. 95-109; CFMM 292, pp. 88-97; SMMJ 169, ff. 111r-118v; SMMJ 170, ff. 279r-282v

Armenian

On the Psalms

ACC 36, ff.165r-170v; AODA 55 (Psalms, with introduction by Epiphanius); APIS 25, ff. 6r-15r; BzBz 229, ff. 28v-38r

Commentary on the Gospels

ACC 65, ff.14r-115r

On the 12 Gems in Aaron’s Breastplate, epitome

BzBz 205, pp. 458-469

Homily collections

ACC 17; APIB 42

Homily for Holy Saturday on Joseph of Arimathea [= On the Burial of Jesus]

ACC 232, ff.217v-236v

Homily

APIA 74, pp. 274-290

Homily in Praise of Mary

APIO 43, ff. 39r-44v

Homily on the Resurrection of Christ and on the Dead who Rose up with Him

APIO 43, ff. 217r-226r

Canonical Letter

ACC 53, ff.134r-138r

Life of Epiphanius

APIB 42, pp. 2-22; ACC 17, ff.7r-19r; ACC 65, ff.3r-13v; BzNc 1029, ff. 82r-85r

Gǝʿǝz

Anaphora of Epiphanius

EMML 294, ff. 119v-126v; EMML 442, ff. 123r-129v; EMML 517, ff. 112r-117r; EMML 956, ff. 142v-148v; EMML 1157, ff. 177r-184v; EMML 1206, ff. 91r-99r; EMML 1434, ff. 75r-80r; EMML 3549, ff. 85r-96r

Manuscripts of the Qerǝllos (a collection of Greek materials translated into Gǝʿǝz for the Ethiopian Orthodox Church; see Alessandro Bausi in Encyclopedia Aethiopica, vol. 4, 287-290)

EMML 639, 688, 747, 1173, 1193, 1669, 1946, 2021, 3595, 4448, 4459, 5005, 5775, 6263

Homily for the Sixth (Day) in Easter Week

EMML 1763, ff. 209r-212v

History of Askänafǝr, a Roman Officer, and the Thirteen Thieves, as told by Epiphanius, Bishop (of Cyprus)

EMML 1479, ff. 119v-121v

Amharic

The Beauty of the Creation [Śǝnä fǝträt], here under the title Aksimaros (Hexaemeron) of Epiphanius (Epiphanius being quoted heavily in the text)

EMML 1210, ff. 2r-34v

*******************************

[i] A Century of British Orientalists, 1902-2001, p. 92, who, in his chapter on Sir Gerard Clauson, was in that instance speaking about the languages of Central Asia.

[ii] Encyclopedia of Buddhism, vol. 1 (New York, 2004), 452-456; Endymion Wilkinson, Chinese History: A New Manual, 3d rev. ed. (Cambridge, Mass. and London, 2013), 62, 384-394; K.R. Norman, “The Languages of Early Buddhism,” in Premier colloque Étienne Lamotte: Bruxelles et Liège 24-27 septembre 1989, (Louvain-la-Neuve: Université catholique de Louvain, Institut orientaliste, 1993), 83-89; and Klaus Röhrborn and Wolfgang Veenker, eds., Sprachen des Buddhismus in Zentralasien: Vorträge des Hamburger Symposions vom 2. Juli bis 5. Juli 1981, (Wisebaden: Harrassowitz, 1983).

[iii] Manichaeism, tr. M.B. DeBevoise (Urbana, Ill. and Chicago, 2008), 31-56 (ch. 2) and 103-105 (bibliography). Note also the multi-volume Dictionary of Manichaean Texts, Corpus Fontium Manichaeorum, Subsidia 2-5, 7 (Turnout: Brepols, 1999-2012). There are several scattered remarks on both Buddhist and Manichaean texts in Old Turkic (Uyghur) in ch. 1 of Marcel Erdal, A Grammar of Old Turkic, Handbook of Oriental Studies, sect. 8, 3 (Leiden and Boston, 2004), 1-36.

[iv] Life of Antony is CPG 2101, Nemesius of Emesa’s On the Nature of Man is CPG 3550, and Titus of Bostra’s Against the Manichaeans is CPG 3575.

[v] See the remarks of the text’s editor, R.P. Blake pp. lxxiii-lxxvii.

[vi] For more details, of course, see the CPG entries themselves.

[vii] See further manuscript information for some of these languages here: https://hmmlorientalia.wordpress.com/2014/07/01/more-on-the-homily-on-the-burial-of-jesus-cpg-3768/.

*Many thanks to Lydia Clare Bremer for her comments, which greatly improved this short note.

As of August 2017 Dr. Adam Carter McCollum will be a visiting associate professional specialist of languages of Late Antiquity in the department of Theology at the University of Notre Dame. He has previously worked as a manuscript cataloger at the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library (Saint John’s University), and he participated in an ERC project at the University of Vienna.