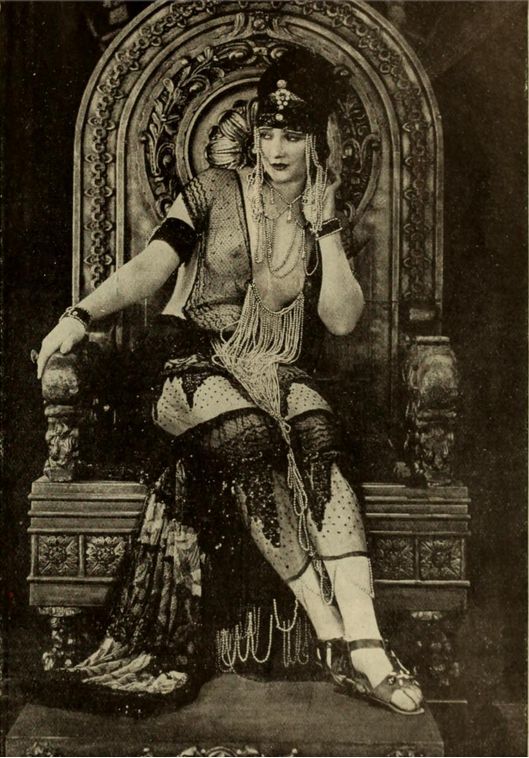

Betty Blythe as the Queen of Sheba, 1921

A Genius for Mentorship: A Forum in Honor of Ben Wright on his 65th Birthday

~ presented by his students ~

Ben Sira as a Baby: The Alphabet of Ben Sira and Authorial Personae

Jillian Stinchcomb

If you’ve never read the Alphabet of Ben Sira, you might not know that Lilith rebelled against Adam because she wanted to be on top during intercourse, a proposition which Adam refused. You also might not know that the Queen of Sheba was an extremely hairy woman who refused to shave her legs, or that Solomon’s penchant for compromise led him to invent a depilatory of arsenic and lime. (Thanks for Nair, Solomon!) The information imparted by Ben Sira in the Alphabet (including but not limited to these tales) stands as an outlier in many ways to the highly conservative aphorisms that are found in the Wisdom of Ben Sira. The potentially surprising literary trajectory represented by the Alphabet indicates new possibilities for thinking about the persona of Ben Sira in Jewish literature.

Although Ben Sira is not an especially well known figure today, he was cited approvingly by the tenth-century author Saadia Gaon; manuscripts of his wisdom found in the Cairo Genizah show characteristics more often reserved for canonical, biblical texts; and he is cited authoritatively in several places in the Babylonian Talmud (for example, b. Hag 13a). In a forthcoming article, Ben Wright argues persuasively that the wide-ranging character of Ben Sira offers a useful site for reflection on the complex medieval afterlives of Second Temple culture heroes. This essay aims to develop the insight Ben Wright has brought to bear on the study of Ben Sira, and reflects on the complex intertextual matrix of the Alphabet of Ben Sira.

Among scholars of Second Temple Judaism, Ben Sira has long been known as the first named author in Jewish literature. More recently this status has been fruitfully interrogated by Eva Mroczek, Hindy Najman, and Jed Wyrick, all of whom question whether our modern concept of “authorship” fits with ancient sources and point instead to an authorizing function for such figures. However we read the Second Temple examples, this is clearly the case for the Alphabet of Ben Sira, a (sometimes lewd) collection of tales from ninth- or tenth-century Abbasid Baghdad. The Alphabet of Ben Sira stands far afield from the Wisdom of Ben Sira, Jubilees, and other ancient texts exhibiting complex relationships to “authors,” and it has parallels of both form and content with the classical rabbinic literature. Precisely because the text utilizes the character of Ben Sira, with much of the work presented in his voice, it poses intriguing questions of continuity and change in Jewish literary production, specifically in relation to the afterlives of Second Temple Jewish texts and traditions in the Middle Ages.

The Alphabet can be divided into three major parts. The first part of the text, called the Toledot in most manuscripts, opens with the story of Ben Sira’s conception. The wicked Ephraimites of Jeremiah’s generation threaten him into masturbating with them in a public bathhouse. Jeremiah’s daughter later enters the bath water where the onanism had taken place and becomes pregnant by her father’s emission, since his seed was holy and therefore preserved. After seven months, Ben Sira is born with all of his teeth and the ability to speak. He immediately uses that ability to tell Jeremiah’s daughter that, via the technique of gematria, the numerical value of the words “Sira” and “Jeremiah” are the same, explicitly introducing into the story one reason for the connection drawn between the two figures. He also peppers his speech with quotations from the Babylonian Talmud, a trend that continues throughout the Alphabet.

After his mother supports him materially for a year at his direction, Ben Sira demands to be taken to an instructor, beginning the second part of the text. Though initially put off by Ben Sira’s youth and irreverent attitude, the teacher attempts to teach the alphabet. For each letter of the alphabet presented by the teacher, Ben Sira responds with an aphorism that begins with the appropriate letter; the teacher often adds embarrassing revelations about himself. All but one of the aphorisms are drawn from a passage in the Babylonian Talmud, b. Sanhedrin 100b, likely the victim text of this parody, as David Stern has argued. Ben Sira’s aphorisms are largely concerned with the dangers that women present in their roles as wives, daughters, or sexually attractive strangers. The subject matter and comedic impulse evoke Judah Ibn Shabbetai’s Judah the Misogynist, a thirteenth-century text that Talya Fishman has convincingly identified as a parody.

These aphorisms are dizzying to read, not only for the embarrassing traits we learn about the teacher and his marital troubles. They seem to move through a variety of registers, from the fairly straightforward “Abstain from worrying in your heart, for worry has killed many” (followed by the teacher’s panicked response: “I don’t have a worry in the world except for the fact that my wife is ugly”) to the borderline nonsensical:

Run away from wicked neighbors, and don’t be counted in their company.

For their feet run to evil, and they rush to shed blood.

Similarly, have compassion for your neighbors, even if they are wicked.

Share your food with them, for when you appear in court, they will give testimony about you.

Like many of the others, this aphorism seems quite wise at first glance, in no small part because it directly contradicts itself in a way that seems like a possibly fruitful paradox. However, it lacks a cogent internal logic, and the frame story does not suggest that a reader ought to take this advice seriously. Within the context of the narrative, it’s hard to read the aphorisms as anything less than sometimes biting red herrings that allow the character Ben Sira to show off his sophistry, connecting inane packets of wisdom and creating a narrative sum that’s more than its parts.

After a few statements on Ben Sira’s ability to learn at astonishing speeds, the text shifts to its third part. At the court of Nebuchadnezzar, his wise men are distressed by the good reputation of Ben Sira in light of their own incompetence. Ben Sira initially refuses an invitation to Nebuchadnezzar’s court, sending his regrets on a message inscribed on the entirely bald head of a rabbit. Upon a second request, he acquiesces and immediately enters into a Talmudic-style disputation with the advisors before answering 22 questions from Nebuchadnezzar. The first of these questions concerns the rabbit’s head, and how it became so hairless. By way of answer, Ben Sira tells Nebuchadnezzar the story of his parents, who are apparently the Queen of Sheba and Solomon (cf. 1 Kings 10:1-13, 2 Chronicles 9:1-12). Ben Sira explains that when the Queen of Sheba visited Solomon, she was very hairy. Though attracted to her, Solomon didn’t want to have sex with such a hirsute woman, so he invented a depilatory made of lime and arsenic to remove her body hair. Thus, Nebuchadnezzar’s mother, the Queen of Sheba, becomes narratively equivalent to the hairless rabbit. In a striking sign of the scholastic background of the composition, this equivalency forms a multilingual pun: rabbits are lagoi in Greek, and the Ptolemies were known as the Lagai, suggesting that Nebuchadnezzar’s mother was an Egyptian queen while his father was an Israelite king, an absurd assertion matched only by the absurdities of Ben Sira’s own conception.

This contrast between the extreme endogamy of Ben Sira and the extreme exogamy of Nebuchadnezzar might suggest another reason Ben Sira is connected to Jeremiah beyond the gematria equivalency noted above. The sixth-century Targum Sheni Esther presents the Queen of Sheba lifting her skirts and revealing excessive hairiness to Solomon, just as the Alphabet does. This episode occurs in an extended excursus which is partly introduced by Nebuchadnezzar’s theft of Solomon’s throne. As the Solomon/Queen of Sheba episode concludes, Targum Sheni Esther shifts gears rapidly to discuss Jeremiah in an unrelated context. The Alphabet may work as a rewriting of this part of Targum Sheni Esther, providing an overarching narrative that connects these characters in contrast to the somewhat disjointed presentation of the Targumic material.

The Alphabet of Ben Sira continues this section with a further twenty-one questions. This section presents the earliest story of Lilith with Adam in Eden, Nebuchadnezzar’s daughter expelling a thousand farts an hour, and answers to such burning questions like why a donkey urinates in the urine of his companion, and why a raven copulates by mouth. Some manuscripts conclude with a fourth section comprising an Aramaic alphabet of much more sincere-sounding aphorisms, but many do not; Yassif’s text critical work (found in the bibliography below) is an invaluable resource for navigating the complex manuscript history. In either case, a rich variety of folk tales are exhibited, many of which indicate the Abbasid, Arabic context for the formation of this work.

The contents of the Alphabet are wild, but some of the most interesting aspects of the study of the Alphabet emerge from textual resonances far beyond any original context. David Stern has named the Alphabet of Ben Sira the first example of parody in classical rabbinic literature; Eli Yassif has called it one of the earliest folk anthologies in medieval Jewish literature. Precisely how one best reads the context and genre of the Alphabet is a live question because, beyond a particularly complex manuscript history, the Alphabet covers such a wide range of topics.

The Alphabet presents a tantalizing example of the increased visibility of Second Temple texts and traditions in medieval Jewish works. In his forthcoming article, noted above, Wright considers the possibility of alternate histories of the character Ben Sira in late antique and medieval contexts, examining book lists from the Cairo Genizah and scattered references in rabbinic material alongside the Alphabet of Ben Sira. He also connects these presentations of Ben Sira to the phenomenon noted by Mroczek. In The Literary Imagination in Jewish Antiquity, Mroczek analyzes ancient discourses around David, Ben Sira, and other figures associated with biblical writing, arguing that these culture heroes colonized new textual areas as authors in worlds full of hidden texts waiting to be revealed.

Complicating the application of Mroczek’s model, the Alphabet does not name Ben Sira as its author, unlike the superscriptions that connect David to the Psalms or Solomon to the Song of Songs. Instead, the bulk of the Alphabet presents Ben Sira’s knowledge in his character’s voice as an authorizing figure. The third-person omniscient narrator, however, suggests a significant shift from the poetics of attribution so ably discussed by Mroczek and Najman before her. Where so-called pseudepigraphical texts utilize the premise of (re)discovery, the third-person outermost frame allows for the possibility of new writing and a comedy that might be otherwise inappropriate in the voice of a (sometimes) revered author-hero.

This authorial shift is particularly striking in light of the fact that the anonymous author shows a nigh-encyclopedic knowledge of rabbinic material, as even a quick glance at the footnotes for the translation found in Rabbinic Fantasies can attest. The rabbinic material is completely intertwined with non-rabbinic and pararabbinic material, such as the Targumic references and numerous examples of folklore known otherwise through Arabic sources. That it does so in an emphatically comedic and playful text underscores the ambivalence of Ben Sira, which is perhaps available precisely because he is a marginal figure in comparison to other culture heroes like David or Solomon, as Wright argues. This ambivalence in conjunction with non-rabbinic material emphasizes that a variety of literary trajectories emerge after the Second Temple period, and these trajectories interact in complex, text-specific ways that are often irreducible to a single body of tradition.

Wright’s work helps us to understand the Alphabet insofar as his research has included treatments of Ben Sira at every stage of his ancient and medieval career as an author/authorizer— from the Hebrew Wisdom of Ben Sira, to its Greek translation of his grandson, to Rabbinic quotations thereof. Scholarship on the Alphabet is somewhat lacking, in no small part due to its outrageous subject matter, although the earliest manuscripts of the Alphabet date to the eleventh century, with print editions from 1519. A handful of articles, included in the bibliography below, have considered the genre and certain philological questions, but very little sustained scholarship on the text is available. Yet for my own work, this text is critical inasmuch it challenges scholarly habits of thought with respect to normativity and rabbinic culture, trajectories of Jewish literary production and, more generally and perhaps more importantly, what is and is not worth studying. In light of this, I am particularly grateful for Wright’s work to integrate the study of the Alphabet with the larger history of Ben Sira and his feedback, interest, and encouragement.

Bibliography

Börner-Klein, Dagmar. “Tell Me Who I Am: Reading the Alphabet of Ben Sira” in Hanna Liss and Manfred Oeming (eds) Literary Construction of Identity in the Ancient World. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2010. 135-144.

Fishman, Talya. "A Medieval Parody of Misogyny: Judah ibn Shabbetai’s ‘Minḣat Yehudah sone hanashim.’” Prooftexts (1988): 89-111.

Ginzberg, Louis. The Legends of the Jews. Vol. 1-7. Reprinted. Johns Hopkins Paperbacks. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Hasan-Rokem, Galit. “An Almost Invisible Presence: Multilingual Puns in Rabbinic Literature,” in Charlotte Fonrobert and Martin S. Jaffee (eds.) The Cambridge Companion to the Talmud and Rabbinic Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007. 222–240.

Najman, Hindy. Seconding Sinai: The Development of Mosaic Discourse in Second Temple Judaism. Supplements to the Journal for the Study of Judaism. Leiden: Brill, 2003.

Nissan, E. “On Nebucahdnezzar in Pseudo-Sirach,” The Journal for the Study of Pseudepigrapha 19.1 (2009): 45-76.

Lassner, Jacob. Demonizing the Queen of Sheba: Boundaries of gender and culture in postbiblical Judaism and medieval Islam. University of Chicago Press, 1993.

Stern, David, ed. Rabbinic Fantasies: Imaginative Narratives from Classical Hebrew Literature. Reprinted. Yale Judaica Series 29. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 1998.

Stern, David. "The Alphabet of Ben Sira” and the Early History of Parody in Jewish Literature." The Idea of Biblical Interpretation: Essays in Honor of James L. Kugel. Leiden: Brill, 2004. 423-448.

Wyrick, Jed. The Ascension of Authorship: Attribution and Canon Formation in Jewish, Hellenistic, and Christian Traditions. Harvard Studies in Comparative Literature 49. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004.

Yassif, Eli. The Tales of Ben Sira in the Middle Ages: A Critical Text and Literary Study. Jerusalem: Hotsa’at sefarim ‘a.sh. Y.L. Magnes, ha-Universitah ha’Ivrit: 1984 (Hebrew).

Yassif, Eli. “Pseudo Ben Sira and the ‘Wisdom Questions’ Tradition in the Middle Ages.” Fabula 23 (1982): 48–63.

***

Jillian Stinchcomb is a PhD candidate at the University of Pennsylvania. She is writing her dissertation on the Queen of Sheba and biblical reception history.