For more reports from PSCO 2017-18, return to the PSCO hub here

Philadelphia Seminar of Christian Origins 2017-18, Meeting #4

Julia Watts Belser (Katz Center/Georgetown): Snakes in the Garden - Sexuality, Animality, and Disability in the Rabbinic Garden of Eden

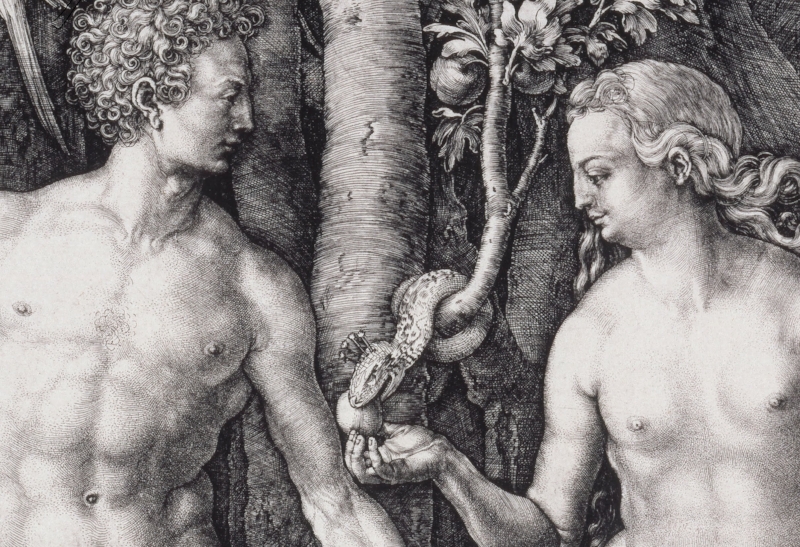

In her talk at the Philadelphia Seminar of Christian Origins on January 25th, Julia Watts Belser explored how characteristic features of embodied—real-life, breathing, slithering, even affectionate—snakes illuminate rabbinic readings of the creature’s appearance in the Garden of Eden. How do the rabbis conceptualize the biblical “cleverness” of the snake? How do such ideas map onto larger questions of human and animal embodiment? Might the example of the snake help us think better about how bodies–especially despised bodies—do conceptual work for rabbis?

Belser illustrated her thoughts with a series of short excerpts from classical Palestinian midrash. Genesis Rabbah 19:1, for example, denies a donkey a suffering body. The midrash pairs intellectual attainment with an increased capacity for suffering, and imagines humans—because of their intellectual capacity—as uniquely susceptible to certain kinds of pain. Belser draws a parallel to Dea Boster’s analysis of the discursive force of disability in African American slavery. Even as a rhetoric of intellectual disability was often used to justify slavery, Boster argues that the discourse of slavery simultaneously represented enslaved persons as hyper-able—and thus, as bodies able to perform and endure physical labor and deprivation without suffering. The donkey, Belser argues, is similarly situated in midrashic discourse: an animal in terms of knowledge, but also physically robust, well-suited to hard labor and immune to the consequences.

The cleverness of the midrashic snake, by contrast, implicates humans and animals alike. When God told Adam not to eat the fruit of That Tree—the tree of the knowledge of good and evil—he said simply: “You must not eat of it” (Gen 2:17). The canny rabbinic snake notices how Eve’s telling expands the divine prohibition: “God said, “You shall not eat of it and you shall not touch it, lest you die” (Gen 3:3). In Genesis Rabbah 19:3, the snake exploits this difference. The serpent, propelled by illicit desire, thrusts Eve against the forbidden tree, “proving” to her that God’s word as she received it is not legitimate. She touched the tree; she did not die. Why not eat?

Literalizing the divine curse that the snake will crawl on its belly, the midrash recounts how angels descend to punish the snake by cutting away his arms and legs, chopping off his human likeness. How might we consider the symbolic and embodied snake in tandem? How to “think,” Belser asks, “more capaciously about the possibility of the snake and the snake’s body?” One midrash asserts that since the snake caused humans to bend (geḥonim) over their dead, thus, he will go on his belly (geḥonkha)—his body mirrors the state he caused in humankind. Another midrash claims the snake stood upright like a human when created, but he desired what he could not have and lost this capacity. The snake’s body slips towards and away from humanness. What can the increased susceptibility of the snake’s body to change reveal about the midrashic account of bodily changes inflicted on the primordial Adam? According the rabbis, Adam’s created body had extraordinary properties, stretching from one end of the earth to the other, but like that of the serpent it was also transformed and reduced.

Each text, rich in interpretative possibilities, sparked fruitful discussion, ranging from the possibility of biblical echoes to comments on midrashic storytelling, to insights drawn from disability studies. How does the removal of the snake’s hands link to the removal of his legs? To what extent is the consolation offered to the snake a midrash generated by empathy, and to what extent does it aim to protect God’s reputation? How do the nuances of the midrash distribute culpability? Whose “fault” is the sin—and is “fault” even the best lens through which to read?

In the Genesis narratives, the primordial Adam, Eve, and the serpent act as a magnet for all sorts of cosmological, astrological, abstract theological speculation. In exploring midrash via the body of snakes, Belser modelled the possibility of approaching this swirl of readings from another trajectory. What happens when we read midrash through the prism of a very specific animal body, reflecting on differences between humans and other animals? How might reading for disability offer insights into the structures and construction of limits and capabilities, a way to think about transformation and change, the promise that bodies offer, the way they evoke complex and contradictory desires?

Julia Watts Belser, currently Research Fellow at the Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies, is Associate Professor of Jewish Studies in the Department of Theology at Georgetown University. She specializes in cultural studies of rabbinic narrative, drawing on queer feminist theory, disability studies, and eco-materialism to inform fresh approaches to both classical rabbinic literature and Jewish ethics, as in her most recent book: Rabbinic Tales of Destruction: Gender, Sex, and Disability in the Ruins of Jerusalem (Oxford, 2017).