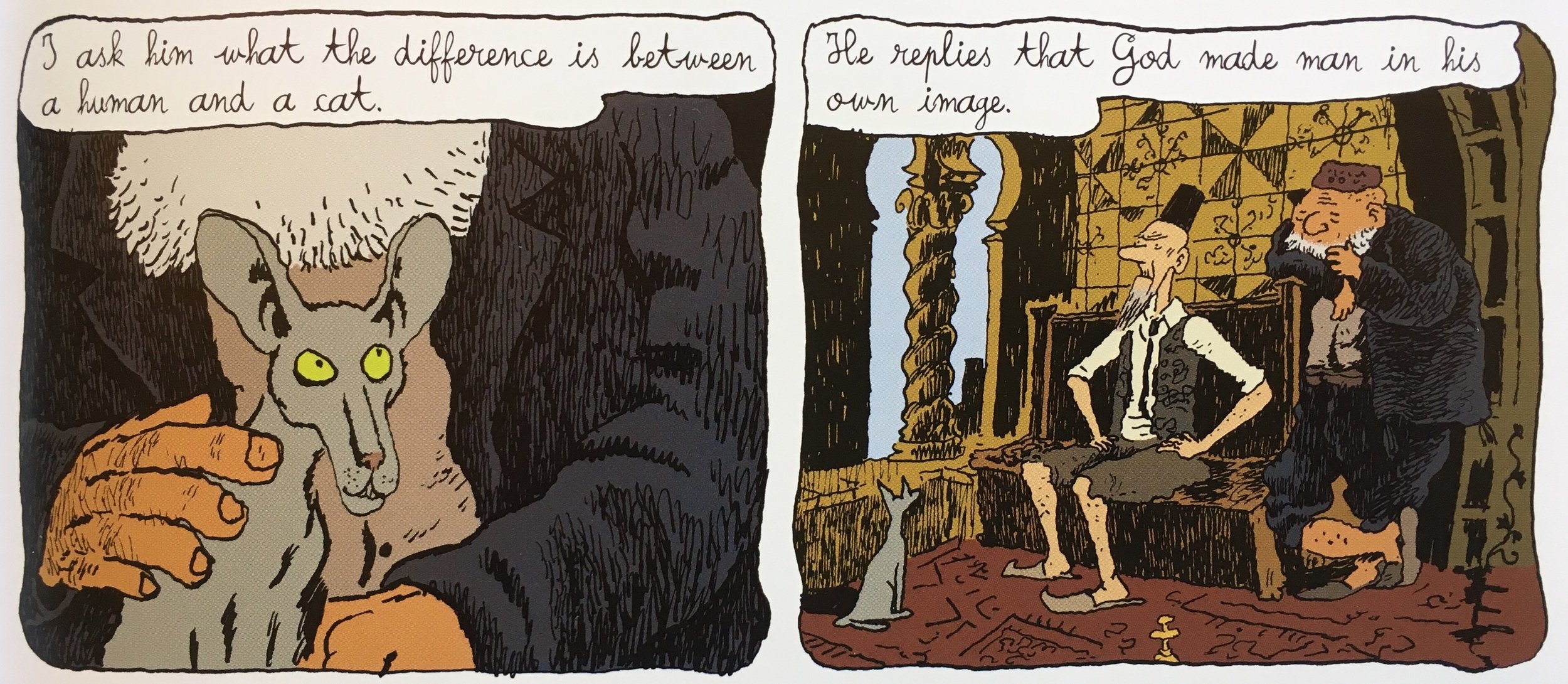

Joann Sfar, The Rabbi’s Cat, New York : Pantheon Books, 2005), 11/3-4 (image used with kind permission of artist)

I. Cat, Chicken, God, Human

In Joann Sfar’s graphic novel (and later, film) set in 1920s Algeria, the rabbi’s cat gobbles up a cacophonous parrot and finds that he can speak to humans. The cat pleads for a bar mitzvah. Befuddled, Rabbi Abraham and his cat visit the rabbi’s own rabbi. The rabbi’s rabbi angrily denies the request, laying down the law of human-feline difference in Genesis 1:26. When the cat insists on seeing a picture of God, the rabbi declares that God is a word. So, the cat reasons, if humans are like God because they have speech, then surely he is like a human. Bested in theological disputation by an animal, the rabbi’s rabbi calls for the cat’s drowning. The stakes of humanness versus animality are immediately apparent: whose life is valued? Whose death is easily imaginable? By what conceptual and material means is difference of kind enacted and enforced?

The artist Sunaura Taylor presses on these very questions in her vivid painting and writing. Many of her paintings interweave animals and people with disabilities forcing viewers to confront a “value system that declares some bodies normal, some bodies broken, and some bodies food.”[1] In Self-Portrait as Chicken, she paints her arthrogrypotic body as a chick, along with her siblings, locking eyes with her mother-hen, mouth agape, or awaiting food. Subverting freakshow imagery and the medicalizing gaze which produce disabled bodies as curiosities or pathologized objects, Taylor stares back showing herself on her own terms, terms that quite deliberately invite comparison to and identification with animals.[2] Taylor finds kin and kind with chicken. Both Sfar and Taylor’s work brilliantly use images to call into question human claims about their status as images. What can scholars of late antiquity draw from these artists’? How might we, too, pull at the reverberations and potentialities of the way humans and nonhumans were conceived in late antiquity?

II. Likeness, Difference, Kind

… I always knew that if I turned up pregnant, I wanted the being in my womb to be a member of another species; maybe that turns out to be the general condition.

Donna Haraway, The Companion Species Manifesto, 96

The human as image of God embodies a model of representation: Adam bears Seth in his “image and likeness” (Genesis 5:3). Despite, or perhaps because of, its mimetic pull, the occlusions are multiple: Genesis 1:26 upholds species separation through hierarchical relation (“and let them have dominion…”), Genesis 5:3 makes for patrilineal generation (goodbye Eve). The human as image of God thus sponsors a theory of reproduction focused on what Haraway dubs “the sacred image of the same.”[3]

The mobilization of likeness as essential to reproduction goes hand in hand with value-laden theories of difference whether around species, gender, race, or disability. Sunaura Taylor demonstrates how dissemblance, or cross-kind resemblance, creates alternate forms of species and kinship. At the same time, her work highlights the webs of (re)productive power. Haraway’s fantasies of xenogenesis openly defy heterosexualized and gendered divisions of reproductive labor. In the work of Sfar, Taylor, and Haraway, attention to the nonhuman, the animal, the species nonconforming, illumines the insufficiencies of accounts of the human that are species-exclusive.

This attention to the nonhuman is not, of course, unique to these contemporary examples. Increasingly, we are finding scholars of late antiquity turning to questions of animality, materiality, and variation. My current work partakes in this turn while drawing on that of artists such as Taylor and Sfar, as well as of feminist science scholars and new materialists, to consider how questions of species intersected with theories of reproduction in antiquity. Late ancient people lived in a world in which the contours of the human were subject to instability and variation. Aristotle, the rabbis, Pliny, and Zoroastrian writers, knew that in a world populated by a plenitude of kinds, with variable and multiple technologies of generation, reproductive outcomes could be unpredictable. Humans, among other kinds, might deliver species nonconforming creatures.

In what follows, I highlight several sources that point to a rabbinic theory of reproduction that has a weak commitment to the dictates of mimetic resemblance. This theory accommodates -- if uneasily-- non-like progeny as members of their parents’ kind. It does this, in part, by recognizing likeness across kinds. Moreover, it embeds humans among other kinds, not only conceptually or comparatively but also gestationally, into the heart of the reproductive process.

III. Gynecology/Zoology/Biology

Early rabbinic ideas about human and animal reproduction – recalling Aristotle's Generation of Animals, Pliny's Natural History, or Pseudo-Aristotle’s Problems – reside in the tractates of Niddah (menstruation), Bekhorot (firstborns), and Kilayim (forbidden mixings of plant and animal species) in the Mishnah. Here is a scenario from Niddah:

… She who expels something like a kind of domesticated animal, wild animal, or bird, whether pure or impure; if it is male she should sit [the days of impurity] for a male and if female she should sit for a female, the words of Rabbi Meir. And the sages say: Anything that does not have something of human form is not offspring.

Mishnah Niddah 3:2

This comes amid a series of scenarios in which women "expel" (or “abort”) various material bodies, which are to be assessed for ensuing ritual purity (and other) implications. In this particular case, there is a dispute about the classification of nonliving organic material in the shape of nonhuman animal kinds (where kind or min is terminology related to species).[4] As in Aristotle's Generation of Animals no-one contests that such events occur.[5] Rabbi Meir insists that such a nonliving entity is offspring, necessitating post-partum purity restrictions. The majority view of the sages, however, ascribes offspring status to this entity only if it satisfies a minimal "human form" requirement. This effectively envisions a hybrid human-animal body.

While the latter requirement seems to retain a vestigial “image of God” concept, the roughly contemporaneous parallel compendium of the Tosefta limits it to the possession of human facial features (eyes and nose but not ears; t. Niddah 4:7). Confounding human-animal distinctions even further, Rabbi Hanina b. Gamliel declares that “the eyeballs of an animal resemble human eyeballs” (t. Niddah 4:5). Reduced to the eyes, “human form” is in fact animal, translating human/animal difference to resemblance.

In the tractate of Bekhorot we find strikingly similar cases to that in Niddah. Take the following:

A cow that gives birth to something like the donkey kind or a donkey that gives birth to something like the horse kind…

Mishnah Bekhorot 1:2

Instead of a human delivering something that resembles a nonhuman, a nonhuman kind delivers another species. The Mishnah initially seeks to rule on whether a donkey delivered by a cow must be donated to the temple if it is a firstborn. However, the question of whether this donkey-like creature born of a cow can be a sacrifice is distinct from its classification. On the latter, the Mishnah asks:

But what about eating them?

If a pure animal gives birth to something that is like an impure kind, it is permissible to eat [the offspring]. If an impure animal gives birth to something that is like a pure kind, it is forbidden to eat [the offspring].

For that which emerges from an impure [kind] is impure and that which emerges from a pure [kind] is pure.

The dietary rules –forbidding/permitting the human ingestion of certain kinds as im/pure-- serve as a classificatory grid. The ruling confirms that a donkey-like creature (or a camel, t. Bekhorot 1:9) delivered by a cow may be consumed. This, despite the fact that camel and donkeys are impure kinds. The principle of generation in the final line declares that it is parentage, rather than likeness, that ultimately determines kind. This comports with Rabbi Meir's ruling in Mishnah Niddah that an animal-like entity delivered by a woman is human offspring. While the majority opinion disagreed and disallowed radically nonconforming delivery as offspring, it did include hybrid entities with minimal human form. And in Tosefta Niddah even this minimal requirement was softened by casting certain human features as animal-like.

Two key conclusions emerge from this brief foray: First, the rabbis place the human side by side with other species in considering reproductive variation. Humanness becomes legible through a broader knowledge of lifeforms: through a "zoology" and a “gynecology” that determine the boundaries and the overlaps between species, and through a “biology” that traces their generation. These rabbinic knowledge formations (or “sciences”) were part of larger late ancient conversations about what constitutes a proper member of a species, in terms of reproduction, resemblance, and variation.[6] Second, likeness was not a necessary criterion for being a member of a species (or if it was, a minimal notion sufficed). In their contemplation of variation and dissemblance, these cross-species scenarios complicate straightforwardly mimetic, or species-separatist ideas of the human.

IV. Flesh Kicks Back

Designating particular permutations of flesh as offspring, menstrua, or otherwise, carried (carries) material (e.g. slaughter, ingestion, sacrifice), economic (e.g. inheritance), ritual (postpartum impurity and sacrifice, corpse impurity and disposal), and affective entailments. In their attempts to classify variation, the male Jewish sub-elites known as rabbis positioned themselves as knowers hoping to shape reproductive potentials and outcomes of non/humans. In this sense the project of the Mishnah is as much a “humanist” enterprise as the imperial knowledge-making projects of Pliny and Galen. As crucial as such observations about the politics of rabbinics knowledge-making are, they remain insufficient.

R. R. Neis, Embryotics for Beginners, 2015, mixed media on paper, 12"x18"

The promise of posthumanist and new materialist efforts to attend to nonhuman agency means registering how nonhumans shaped shared worlds. This has important implications for not only for the sources (e.g. alternatives to “image of God”) and the questions (beyond “rabbinic anthropology” or theology) we tend to privilege. Attending to traces of intertwined human-animal histories can also allow multiple, sometimes contradictory narratives about what it meant to exist in these shared worlds, which in turn allows us to refigure the dynamics and subjects –human and otherwise-- of late ancient scholarship. This has particular promise in the study of late antique rabbinic knowledge formation.

In the case of the rabbis, the complex socio-political entailments of living under an imperial regime and emerging as a small community self-charged with amassing and preserving scholastic traditions mean that their knowledge-making has often been framed through grids of influence vs. resistance and authority vs. marginality. Getting beyond binary models of agency/passivity, or subordination/resistance makes for subjects --human and nonhuman-- that are simultaneously constituting and constituted. This is invaluable for dealing with the multiple and intersecting vectors of imperialism, gender, race, ethnicity, animality, species, and more at play in our sources. Historians, already trained in teasing apart complex, plural causalities, have additional approaches through which to track the staggered, relational, mutual, overlapping dynamics through which those entities named as Romans, rabbis, women, animals, and other material (or immaterial) entities were constituted/constituting.

The insights of posthumanist and feminist new materialist scholarship and their recalibrated accounts of agency encourage us to imagine how human and nonhuman substances impinged upon their knowers in material (even if not in determinist) ways. As ostensible knowers (bound up themselves in complex sociopolitical constraining/productive or constituted/constituting frameworks) and products/producers of humans amid the messy and intertwined reproductive and bodily materials of women and animals, the rabbis offer a rich opportunity for this kind of analytical retuning.

V. Non/Humans in Late Antiquity and the Present

In thinking about the human in ancient Jewish studies and early Christian studies, many have focused on the ancient afterlives of “the image of God” (though its presence in the early rabbinic corpus is slender). It is undeniable that this conception of the human and attendant notions of likeness and reproduction have, by their logics of inclusion and exclusion, had material effects on the value and lives of a variety of beings. In my own work, I acknowledge these logics while seeking to avoid their reduplication by looking at some unlikely rabbinic sources. These sources point to human implication among other kinds, particularly in reproductive contexts. I try to refrain from naturalizing the human as an analytic unit, instead historicizing its production, maintenance, and disruption, among other entities. I have found allied and overlapping theories and methodologies lumped together under the heading of “posthumanism,” i.e. feminist new materialisms, feminist science studies, animal studies, and disability studies, to be incredibly productive for this kind of task. These approaches summon the agency of entities consigned to “mere” material, offering opportunities for re-thinking dualistic binaries. Feminist science studies seek to account for the complex ethno-racial, political, and gendered dimensions of power/knowledge dynamics without reinstating a clear cut between the material and the semiotic, or between nature and culture (Haraway, Karen Barad, Mel Chen, Myra Hird, Michelle Murphy). Disability studies (Alison Kafer, Sunaura Taylor, Rosemary Garland) alongside animal studies (Haraway, Chen, Taylor), and critical race studies (Chen, Alexander G. Weheliy), engage the histories of varied vectors of normativity and nonconformity. In late antiquity scholars such as Julia Watts Belser, Beth Berkowitz, Denise Kimber Buell, C. Mike Chin, Aileen Das, Rebecca Fleming, Charlotte Fonrobert, Rebecca Futo Kennedy, Heidi Marx, Annette Yoshiko Reed, Kristi Upson-Saia, Max Strassfeld, and Mira Wasserman are among those working in similar directions. Insights from this rich trove of scholarship on antiquity/modernity have been my companions as I’ve sought to press on the dissonant, resonant, salutary, and disturbing ideas about non/human entities embedded in the Mishnah and beyond.

To the extent that concerns about the human, species, animality, and reproduction criss-cross antiquity and the present, a species-informed approach to late antiquity not only allows us to hazard ways of thinking/being the non/human, it also can short-circuit rhetorical invocations of a “Judeo-Christian tradition” by falsifying cherished myths. The slippery gestatory and gustatory entanglements posited by the rabbis make for a world in which humans and nonhumans are saddled together, in life and in death, in stomachs and in uteri. These are other ways of knowing/being with the limits, ends, end, and propagation of human and nonhuman life.

R. R. Neis is a scholar of ancient Jewish history as well as an artist working primarily in visual media. Neis is appointed in the Department of History and the Frankel Center for Judaic Studies at the University of Michigan and holds the Jean and Samuel Frankel Chair in Rabbinic Literature. Author of The Sense of Sight: Jewish Ways of Seeing in Late Antiquity, Neis’ research and teaching encompass ancient science, material culture, and comparative legal theory. Neis is currently working on a book at the intersection of rabbinics, ancient science, and feminist science studies, entitled Generation and the Reproduction of Species: Rabbinic Biology in Late Antiquity.

[1] Sunaura Taylor, “Beasts of Burden: Disability Studies and Animal Rights,” Qui Parle: Critical Humanities and Social Sciences, 19/2,(2011):191.

[2] Rosemary Garland Thomson, “Staring Back: Self-Representations of Disabled Performance Artist,” American Quarterly 52.2 (2000) 334-338.

[3] Donna Haraway, “Promises of Monsters,” in Cultural Studies ed. L. Grossberg, J. Ratway and J. M. Wise (New York: Routledge, 1992), 324.

[4] Rachel Neis, “The Reproduction of Species: Humans, Animals and Species Nonconformity in Early Rabbinic Science,” Jewish Studies Quarterly 24/4 (2017): 289-317.

[5] Aristotle, Generation of Animals 767b–769b, ed. and tr. A. L. Peck (Loeb Classical Library, vol. 336), 401-419.

[6] On critical and feminist science studies and reading rabbinic sources as “science” see Neis, 2017, 297-300; on ancient Jewish sciences see Annette Yoshiko Reed, “‘Ancient Jewish Sciences’ and the Historiography of Judaism,” in Ancient Jewish Science and the History of Knowledge in Second Temple Literature, ed. Jonathan Ben-Dov and Seth Sanders (New York: New York University Press, 2014), 195–254.