If you were to walk into my “Bible and Its Interpreters” course on a Friday morning, you’d encounter a noisy roar. Seated in pairs, heads bent over photocopied pages, students from all walks of life read aloud from a smattering of texts—last week Enoch, this week the Babylonian Talmud, next week the Qur’an.

I teach all of my 200-level Judaism foundation courses at Kenyon College on Monday/Wednesday/Friday mornings. This past year I dedicated every Friday to chavruta. Chavruta (חַבְרוּתָא, lit. "friendship") is a traditional Jewish method of text-study in which a pair of students read/translate a classical Jewish text out loud and debate its meaning and merits. Learning in partnership acknowledges that one cannot derive a text’s meaning on one’s own, and this logic is echoed throughout rabbinic literature. Rabbi Yose b. Hanina insisted that those who study Torah alone grow foolish (B. Berakhot 63b) and R. Hama b. Hanina likened the relationship to iron sharpening iron (Genesis Rabbah 69:2). The concept lends itself particularly well to rabbinic texts, which layer tradition and redaction in a puzzle-like assortment of meaning. Nonetheless, I have found that chavruta has deep pedagogical value outside traditional circumscribed Jewish text-study and is both a flexible and valuable strategy in the religious studies classroom.

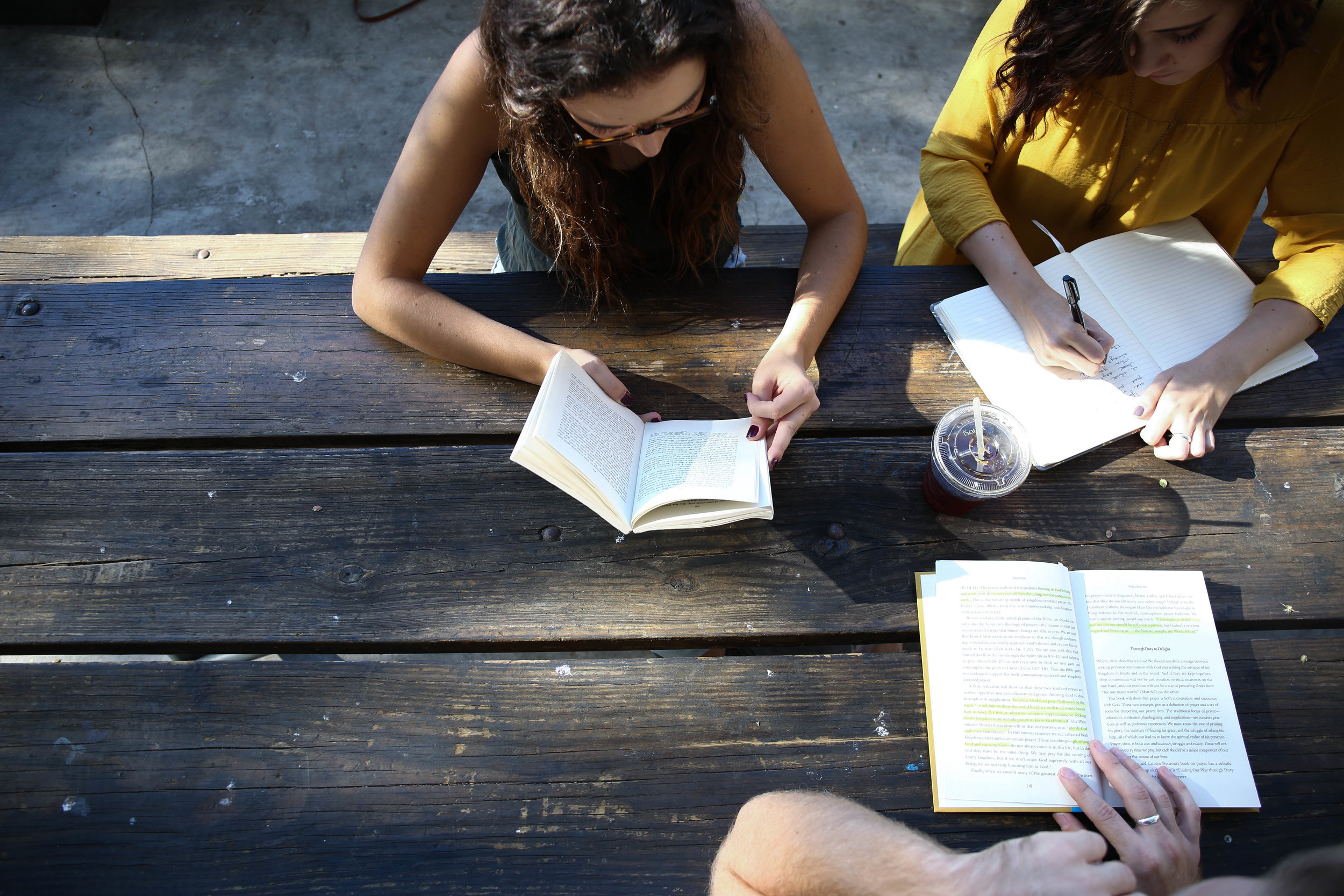

On the first Friday of the semester, I announced the assigned chavruta pairs. Students shuffled awkwardly to their partner and looked sheepishly over the text as I encouraged them, “Read! Read out loud!” While every text is in translation, I wanted to retain the audible force of traditional chavruta and therefore broke the ice of forced partnerships by transforming reading itself into a communal act. Traditional chavruta study emphasizes that before debating what a text means one must first know what it says. Audible reading forced the students to slowly examine the plain meaning of the text with their partner. Soon the awkwardness dissipated as more and more voices filled the air with their clamor.

I encouraged the students to read in chunks, taking turns reading aloud, and pausing to dissect each section. I intentionally photocopied the primary sources so that they could annotate the text—circling unknown phrases, writing questions, marking surprising lines. As the students worked through the text, I circled around the room answering questions that arose or engaging interpretive debates.

After 30 minutes or so of the 50-minute class passed, I called the class to attention. Together for the remainder of class, we discussed their observations, questions, and insights. By the end of the semester in my Bible and Its Interpreters course, my students had read selections from a range of primary sources: Tanakh, Dead Sea Scrolls, the Ethiopian Kebra Nagast, the book of Tobit, the Qur’an, and rabbinic and patristic texts. I framed this Hebrew Bible course in terms of its varied interpretations, using Friday chavruta study as an opportunity to trace the Bible’s reception as a class. Each primary text fit with the topics of the week. I knew the students, in fact, had read the primary texts because I devoted course time to them. Together we built a base of textual knowledge we could draw on throughout the semester.

There are both pedagogical and practical merits to this method. Turning every Friday into chavruta study meant one less prep for this newly minted professor. My colleagues teaching other religious traditions have remarked that they’d love to integrate this “Jewish method” into their own courses for similar reasons. Yet beyond the ease of lecture writing and prep, chavruta cultivates a culture of active learning in the classroom. Fridays became a space to immediately apply the learning acquired throughout the week, using a particular text to illustrate and complicate the students’ understanding. Chavruta anchored the course content to individual case studies that the students could reference on exams or in our other class sessions. Even more so, the students practiced listening to the “Other;” both in the texts themselves and in their partnership.

Reading primary texts in a college class is not in itself an innovation. Primary texts are the bread and butter of much of the humanities. What is particular about chavruta study is the way classroom time and space are changed by a culture of habitual partnerships. Class discussion became normal and expected. I saw greater participation in class-wide discussion because a) everyone had done the reading and b) everyone had already discussed the text with their partner. In the process, students met their classmates, formed intellectual relationships with them, and felt more at ease sharing in the classroom throughout the semester.

Additionally, chavruta learning disrupts the notion that there is a singular meaning of the text. Chavruta operates on debate, often punctuated with loud and impassioned responses to proposed interpretations. Together we explored the possibilities of interpretation while cementing the memory of the concepts found in the text through partnered discussion. We modeled that meaning does not arise in isolation but through conversation and companionship. Partnered learning is not just an activity; it is a culture; a culture that lends itself well to the goals of the religious studies classroom.

Krista Dalton is an Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at Kenyon College.