Trees and Text: A Material Ecocritical Exploration of Gen. 2:4b–3:24 in The Green Bible

R. B. Hamon, (PhD Thesis, The University of Sheffield, UK, 2019).

Engaging with material ecocritical theory, my thesis has two points of focus. First, I examine the depiction of trees in Gen. 2:4b–3:24 in the specific text of the Green Bible.[1] Secondly, I explore the Green Bible itself as text with an explicit environmentalist agenda that is produced and interpreted within a complex assemblage of forestry, manufacturing, publication, distribution, and marketing. While these two analytical approaches are ostensibly discrete they represent two modes of inquiry that are unique to material ecocritical discourse: ‘matter in text’ and ‘matter as text’, respectively. This approach places trees at the center of my study; narrated trees are the focus of my textual analysis of Gen. 2:4b–3:24 and real-world trees are the primary natural material from which the text of the Green Bible is manufactured.

Before proceeding, I should acknowledge that material ecocriticism draws heavily upon new materialist theory; as such, it is fraught with neologisms and complex concepts that span the fields of theoretical physics, philosophy, anthropology, and political theory. With this in mind, I have endeavored to minimize the theoretical aspect of my thesis here in order to focus upon the findings that will be of most interest to readers of Ancient Jew Review.

In essence, ‘matter in text’ is concerned with examining the depiction of the physical world in texts through engagement with new materialist theory.[2] Consequently, my ‘matter in text’ analysis of Gen. 2:4b–3:24 in the Green Bible focuses upon the depiction of trees in this text. The tree of life and the tree of knowledge of good and evil attracted a significant amount of attention from the historical-critical scholars of the last century, who examined these two trees in order to propose various hypotheses relating to the development of the text into its final form.[3] But other than this, the trees of the Eden narrative have received little attention from scholars, even from those offering ecological readings of the text. In response to this gap in knowledge, my analysis uses textual data from Gen. 2:4b–3:24 (both explicit data and possibilities that may be inferred due to narrative omission) to explore the material attributes of the trees of this passage; their size, age, scale, and the various agencies that they exhibit, including their environmental and physiological impacts.

This analysis led me to propose a solution to the classic narrative ‘problem’ of why Yhwh prohibits eating from the tree of knowledge, but not the tree of life, despite both actions being undesirable (Gen. 2:16–17; 3:22–24). This problem has attracted great attention from scholars and most recently Stordalen and Mettinger have each offered highly creative solutions.[4] However, my analysis found limitations with both of these hypotheses and I proposed a solution that is based upon considering the material attributes of the tree of life and tree of knowledge. Developing my work in the article ‘Garden and “Wilderness”’ and considering the botanical attributes of these two trees, I proposed the following explanations for why eating from the tree of life may not have been prohibited by Yhwh.[5] (1) The tree of life had not yet yielded any produce at the time the prohibition on the tree of knowledge was issued. (2) The produce of the tree of life is difficult, but not impossible, to access; for example, imagine that produce of the tree was physically out of reach of the humans, either because of its height off the ground or because of the trees’ dense foliage. (3) The produce of the tree itself dissuades the humans from eating it; for example, like the real-world durian, it may be encased in a tough or spiky shell, or it may emit an unpleasant odor.

These possibilities are based upon gaps in the narrative of Gen. 2:4b–3:24 and as such, cannot be argued as definitive solutions to this problem. Equally, however, nothing in the pericope undermines any of these possibilities. In any of the above scenarios, humans are never made aware of the tree of life, they never eat from this tree, and once they gain an awareness of the tree they are exiled from the garden to prevent them from taking measures that would enable them to eat from it.

This solution raises the question of why the tree of life and the tree of knowledge are placed in the garden of Yhwh at all, if consumption of their produce is forbidden. Considering this question from an ecocentric perspective, I proposed that alongside adding beauty to the garden and yielding edible produce (though not produce intended for human consumption), these trees were placed in the garden to be maintained by the human, consistent with the appointment of the human in Gen. 2:15.

In respect to the agencies exhibited by these two trees, the tree of life apparently possesses an agency associated with divine prerogative; it is capable of imparting eternal life. Whilst at no point in Gen. 2:4b–3:24 does the tree of life actually demonstrate this ability, the agentic potential of this tree is sufficient to motivate Yhwh to take a series of extraordinary measures to restrict the humans from gaining access to it. I argued that contrary to Christian theological tradition that maintains that the humans are exiled from the garden as punishment for their behavior, Gen. 3:14–24, and in particular Gen. 3:23, reveals that the agentic potential of the tree of life is the sole motivator for Yhwh to expel the humans from the garden.

The agency of the tree of knowledge is evident in the physiological change that it instills in the humans, who gain an awareness of their nudity due to eating from the tree (Gen. 3:7). The precise change undergone by the humans is not elucidated in Gen. 2:4b–3:24, though Gen. 3:22 confirms that eating from the tree has imparted the knowledge of good and evil to the first human. A secondary consequence of eating from the tree of knowledge is the series of irreversible punishments precipitated by Yhwh in Gen. 3:14–24. Notably, the tree of knowledge is never punished or held accountable for its role in tempting humans to eat its produce by virtue of its visual allure (Gen. 3:6). The text of Gen. 2:4b–3:24 itself and the subsequent interpretation of this text in Jewish and Christian theological traditions have therefore failed to acknowledge the agency of the tree of knowledge in this respect.

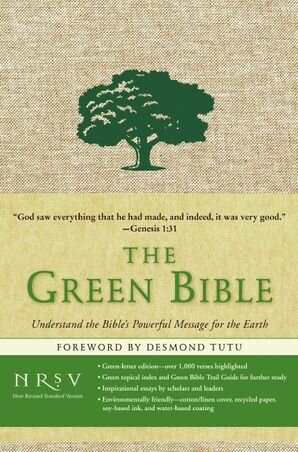

I used the concept of ‘matter as text’ to examine the materiality of the pericope Gen. 2:4b–3:24 as it is rendered in the Green Bible, a specialty Bible published by HarperCollins with an explicit environmentalist agenda. I discussed the potential influence of this specific material format upon its readers and the relationship between the environmentalist ideology of this Bible and the complex global network of natural resources and human efforts that have produced it.

Perhaps the most distinctive, and controversial, feature of the Green Bible is its use of green text to highlight Bible verses that in some way relate to environmental stewardship. I conducted the most comprehensive survey of the green text in this volume to date. I established that whilst the editorial team of the Green Bible outlines their criteria for identifying passages highlighted in green text in the introduction to the volume, in practice the application of these criteria is inconsistent and on some occasions text highlighted in green actually contradicts these criteria. This inconsistency is evident in Gen. 2:4b–3:24.[6] Furthermore, this passage is almost completely highlighted in green ink to the point where its non-highlighted text (rendered in black ink) is actually more visually prominent to the reader than the paler green ink; the opposite effect intended by the publisher.

In respect to the wider features of the Green Bible and how they might influence a reader’s interpretation of Gen. 2:4b–3:24, the supplementary features of the Green Bible frequently present Gen. 2:15 as the key verse of Gen. 2:4b–3:24, and indeed a key Bible verse for ecological hermeneutics. The Green Bible argues that the appointment of the first human as ‘tiller’ and ‘keeper’ of the garden of Yhwh is presented as commissioning of humanity as a whole to look after the entirety of the non-human world. This interpretation is problematic as it is both illogical and anachronistic to impose this contemporary notion of stewardship onto this verse, which, as part of an ancient Western Asian creation narrative, speaks only of the duty of the first human to look after the garden of Yhwh.

Secondly is the issue of sin. The title of Genesis 3, ‘The First Sin and its Punishment’, and the theme ‘The Full Impact of Sin’ in the ‘Green Bible trail Guide’ encourages the reader to interpret Gen. 2:4b–3:24 in terms of sin and punishment, that is to say in a manner consistent with Christian theological tradition, despite there being no mention of sin in the passage itself. Furthermore, this interpretation is in conflict with the notion of stewardship advocated elsewhere throughout the Green Bible; to what extent is it worth caring for a fundamentally ‘corrupted’ world? The Green Bible does not address this apparent inconsistency that is evident within its own environmentalist ideology and this has the potential to confuse the manner in which the reader understands Gen. 2:4b–3:24, and indeed the biblical text of the Green Bible as a whole.

Finally, according to material ecocritical theory, the environmentalist message that is prominent within the textual content of the Green Bible and the environmental and socio-cultural impacts of its production, distribution, marketing, and interpretation represent two interconnected narratives associated with the Green Bible as a material-discursive object. I established that these two narratives appear to be in conflict with each other. The Green Bible presents an environmentalist ideology that is evident in both its visual design and its textual content. The two key elements of this ideology are environmental stewardship and social justice, and these themes are prevalent throughout the volume. Given this ideological focus, one might expect that the Green Bible is produced using methods that accord to the highest standards of environmental and social wellbeing.[7]

However, within the pages of the Green Bible, there is no explicit information relating to the environmental and social impacts of its production. On the rear cover of the volume is a small panel containing information relating to the Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC) certification of the paper used in its production. Through the FSC website, I was able to trace the location of the company that printed the Bible. Due to the ambiguity of the particular type of FSC certification awarded to the Green Bible, it was not possible to trace the provenance of all the paper used in its production. Consequently, it was not possible to determine whether all the paper from which the Bible was made originated from environmentally and socially well-managed sources as its rear cover claimed. The Green Bible as a material-discursive object is, therefore, to some extent, in conflict with itself; its ideological call for environmental and social wellbeing is undermined by its failure to acknowledge the potentially negative environmental and social impacts related to its own production.

A year has passed since I submitted my thesis and during this time I have been reflecting upon what impact this study might have. The study covers a wide ground; developing material ecocritical theory and methodology, contributing to the existing methodologies used in the study of textual materiality, offering a comprehensive and detailed treatment of the trees of Gen. 2:4b–3:24, and exploring the Green Bible in greater depth than any previous analysis. As such, I can see my work being of interest to scholars working in these areas, along with those interested in ecotheology and plant philosophy. Towards the end of my Ph.D., I was informed by HarperCollins that the publication of the Green Bible in physical formats had ceased. The volume is still available in ebook formats, however. This raises further questions about how the materiality of these formats might influence readers as they engage with the Green Bible through various electronic devices and to what extent the myriad natural resources, human efforts, and cultural systems related to producing the Bible in these formats are compatible with the environmentalist ideology of the text.

[1] The Green Bible (London: HarperCollins, 2008). Published in 2008, the Bible has been available in fabric cover, paperback, and ebook formats, in addition, there are UK and US versions of these formats that feature different introductions. This study examines the UK paperback edition.

[2] Serenella Iovino and Serpil Oppermann, ‘Introduction: Stories Come to Matter’, in S. Iovino and S. Oppermann (eds.), Material Ecocriticism (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2014), pp. 1-17 (2).

[3] For a summary of this scholarship see Tryggve N. D. Mettinger, The Eden Narrative: A Literary and Religio-historical Study of Genesis 2–3 (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2007), pp. 5-11.

[4] Terje Stordalen, Echoes of Eden: Genesis 2–3 and Symbolism of the Eden Garden in Biblical Hebrew Literature (Biblical Exegesis and Theology, vol. 25; Leuven: Peeters, 2000), pp. 229-233; Mettinger, The Eden Narrative, pp. 37-40.

[5] R. B. Hamon, ‘Garden and “Wilderness”: An Ecocritical Exploration of Gen. 2:4b–3:24’, The Bible and Critical Theory, 14.1 (2018), pp. 63-86 (77).

[6] For example, Gen. 3:17–19, which depicts the punishment of the first man, is rendered in green ink. Whilst this is understandable given that this passage depicts a relationship between humanity and nature, Gen. 3:14–15, a similar passage that depicts the punishment of the snake, is rendered in black ink.

[7] Indeed, the rear cover of the Green Bible claims that it is ‘[t]he first Bible printed on paper from environmentally and socially well managed forests’.