The Ascension of Isaiah is ‘having a moment’—increasingly receiving the attention it deserves, from those working across the spectrum of disciplinary interests and approaches to ancient texts. As an early Christian apocalyptic text with various distinctive features—a seven-storied cosmology, a quirky angelomorphic christology, and a hierarchical trinitarianism—the Ascension of Isaiah is now recognised as an important, if under-researched, source for understanding early Christian thought. Its adaptation of a Jewish monotheistic framework to encompass the worship of Jesus ‘the Lord Christ’ as ‘the Lord God’ (9:5) constitutes important evidence for our understanding of the origins and development of Christ-devotion and ‘christological monotheism’.

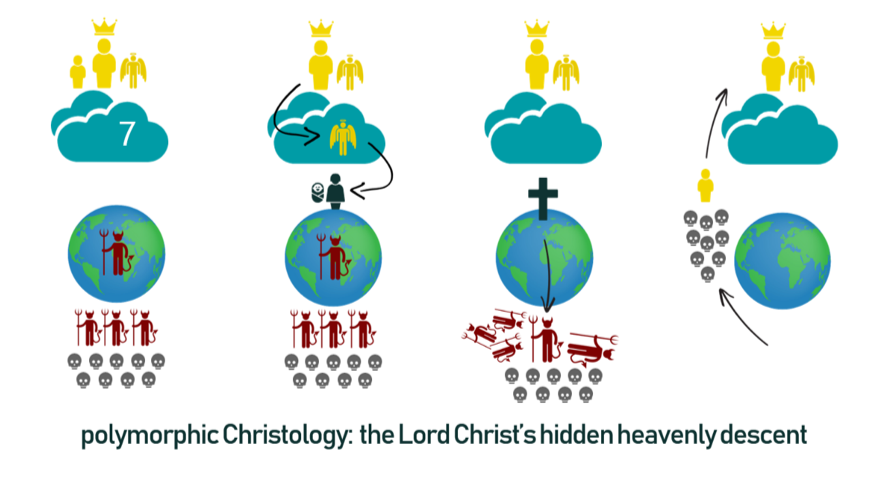

Jesus is presented as the pre-existent, only-begotten Son of the Heavenly Father, who is divinely commissioned to descend from the right hand of God through the seven heavens, in the guise of a holy angel, and then to descend further to the earth in the form of a man, and finally to descend into Sheol in the form of an angel of lawlessness (10:7–15). These metamorphoses function to conceal ‘the Beloved One’s true heavenly identity and thereby facilitate his defeat of Satan, Sammael, Beliar and all their angels who oppressively rule the world and the realm below. They will slay him on the cross, ‘not knowing who He is’, thinking that he is flesh and a man, only for him to slay them in a surprise attack, and ascend to his heavenly throne in undisguised glory, along with the liberated spirits of the faithful departed (9:12–16). The plot is akin to a cosmic spy drama: the heavenly agent descends undercover on His Majesty’s secret service with a strategic mission to assassinate the enemy and liberate the world. In Sheol, they can’t kill him, because he’s already dead. The narrative framework of this ‘polymorphic’[1] christology may be represented graphically as follows:

I’d like to offer here a brief introduction to the prophet Isaiah’s mystical vision of the incarnation of the divine Son in chapter 11, which is attentive to this cosmological framing. I want to highlight that the narrative of Jesus’ birth is deeply embedded within, and profoundly shaped by, the book’s over-arching motif of hiddenness. Just as the Beloved One’s descent through the heavens is a hidden descent, in order to hide his true identity from his opponents, so also the Beloved One’s birth is a hidden birth.

Chapter 11 begins with the familiar: an affirmation of parthenogenesis. Mary’s status as a ‘virgin’ (Gǝʿǝz: ድንግል, dəngəl) despite her pregnancy, and Joseph’s acceptance of her as such following an angelic visitation, is in close agreement with Matthew’s use of canonical Isaiah’s prophecy that ‘the virgin (Gk. παρθένος, parthenos) shall conceive and bear a son’ (Matt. 1:23; cf. Isa. 7:14 LXX). Mary’s birth-giving is then detailed, with a particular emphasis on the element of surprise. Jesus’ birth is described as happening ‘straightaway’, in a manner that astonishes Mary (v. 8). No labour is mentioned; she simply ‘looks with her eyes’ and sees a ‘small child’ (vv. 8, 17). The language approximates what is found in a heavenly vision of the divine Son in the Coptic gnostic Apocryphon of John, wherein the seer recalls that ‘straightaway’ the heavens opened (20:19) and ‘behold, a little child appeared before me’ (21:4). Apparently, the idea is inspired by Isaiah 11:6–9, where ‘a little child’ features in utopian scenes of peace that symbolise the messianic age, which were read christologically in the second century by Irenaeus (Dem. 61) and Hippolytus (Elench. 6.42.2). The author’s choice of an Isaianic pseudonym indicates that the work is designed to be read in conjunction with Isaiah, and invites the attentive reader to notice such intertextual connections.

The possible influence of Isaiah 66:7–9 is also worth considering, since its image of personified Zion’s miraculously sudden birth—a figure for the swift restoration of the nation—signals divine saving action:

Before she who was in labour gave birth,

before the pain of her pangs came,

she escaped and gave birth to a male.

The thought being developed there is that what seems implausible or even impossible—a swift return from Babylonian exile, a precipitous and painless birth—is nevertheless possible for God. A messianic reading of Isaiah 66:7 as a description of the messiah’s birth is attested in Targum Jonathan: ‘Before distress shall come upon her, she shall be delivered; before trembling shall come upon her, as pains upon a woman giving birth, her king shall be revealed.’ Irenaeus (Dem. 54) explicitly relates the prophecy to the inopinatus (‘sudden’ or ‘surprising’) manner of Jesus’ birth. It seems likely, then, that the Ascension of Isaiah’s portrait of Mary’s immediate and painless delivery is modelled on this Isaianic prophecy of the immediate and painless delivery of Zion, in order to signal its christological fulfillment. The logic is that Mary’s delivery is a special kind of delivery, because her son is no ordinary son; he is ‘the Lord Christ’ (4:13; 9:5, 17; 10:7).

Mary’s reaction to her sudden parturition is one of amazement: she is three times described as ‘astonished’ (Gǝʿǝz: ደንገፀ, dangaḍa). The term is theologically loaded and likely designates something more than the shock that often follows a woman’s experience of rapid labour. In the Gǝʿǝz translation of Luke, it is used for Mary’s reaction to the Annunciation, and more generally for the dismay of someone who experiences an angelophany or a theophany. The language of Mary’s response thus functions to point the reader to the heavenly origin of the child. In contrast, Joseph’s response distinguishes him as a secondary participant in the drama: he does not see the child at first but only after his eyes are opened by God (v. 10). Thus the narrative emphasises the incarnate Son’s hiddenness. Discerning the infant Son is not simply a matter of human observation but divine revelation.

We find in verse 9 an intriguing remark about the immediate return of Mary’s uterus to its pre-pregnancy condition: ‘after she had been astonished, her womb was found as it was at first, before she had conceived’. This is generally understood to imply that Mary’s body is not damaged by the birthing process—that she miraculously retains her virginity in partu.[2] The idea, attested as early as Ignatius (Eph. 19:1) and expounded at length in the Protoevangelium of James, became a key point of early Marian discourse. But here, mariology is very much at the service of christology. The fact of Mary’s birth-giving is kept secret by the miraculous reversal of its biological effects, because this furthers the concealment of the divine Son’s arrival in the world, which the couple are forbidden to announce (v. 11). Her maternity is undetectable, in order that her son might go undetected.

Verses 12–15 offer an apologetic rebuttal of two rumours about Jesus’ origins said to be circulating in Bethlehem—and well attested in early Christian discussion of Jesus’ birth, in the Acts of Peter (24), and patristic citations of the Apocryphon of Ezekiel (fr. 3). The author’s interpretation of the testimony ‘the virgin Mary has given birth before she has been married two months’ (v. 13), is not that Mary had engaged in illicit sexual intercourse. That would call into question his christological reading of Isaiah 7:14 that ‘the virgin will be pregnant and bear a son’. The author’s interpretation of the second testimony that ‘the midwife did not go up (to her), and we did not hear a cry of pain’ is not that Mary ‘has not given birth’ (v. 14). Those who think otherwise are characterised as ‘blinded concerning him’ in that ‘they do not know where he was from’ (v. 15). That is, they do not appreciate that Mary’s delivery was neither illicit nor fabricated, but divinely aided, in order to conceal the Son’s descent to earth. Mary’s fast, painless and unassisted labour not only casts her as an anti-type of Eve, whose childbearing was cursed by God (Gen. 3:16), but even more so as a ‘type’ of Jochebed, whose surreptitious childbearing kept the infant Moses hidden from hostile rulers who sought to kill him (Exod. 1-2). The dispute with the putative Bethlehemites over how or whether Mary gave birth is fundamentally a dispute about Jesus’ identity as the pre-existent Son who arrives like ‘the new Moses’.

The emphasis on the abnormal aspects of Mary’s childbearing prompts reflection on whether the text conveys a real birth of a real man, or an appearance which circumvents the usual modes of human entry and human being in the world. The emerging consensus is against a ‘non-birth’, in view of the unqualified affirmations of Mary’s conception (v. 9), pregnancy (vv. 3, 5), and changing uterus (v. 9), which seem to indicate ‘a real human birth, even if a miraculous one’[3]. The genuine corporeality of Jesus is also taken for granted in the unqualified mentions of his persecution, torments, crucifixion, burial and bodily resurrection, which neither softens nor mitigates his enfleshment (3:13–20; 4:13; 9:14, 26; 11:19–21). The special manner of Jesus’ birth, then, does not seem to amount to a denial of his humanity, but an expression of the scheme of the Beloved One’s hidden heavenly descent. What is said about Mary is controlled by the author’s polymorphic christology, and points beyond her to the heavenly identity of her Son, whose human body does not reveal but hides his true self for the duration of his earthly life.

So, we find that Jesus’ hidden birth is an integral scene in the Ascension of Isaiah’s cosmic drama of secret redemption. It leaves us, I hope, with plenty of food for thought.

Emily Gathergood is a PhD candidate in New Testament at the University of Nottingham.

[1] The term is coined and defended by Jonathan Knight, ‘The Christology of the Ascension of Isaiah: Docetic or Polymorphic?’ in The Open Mind: Essays in Honour of Christopher Rowland, ed. Jonathan Knight and Keith Sullivan (LNTS; London/New York: T. & T. Clark, 2015), 144–164.

[2] See the discussion in Thomas Karmann, ‘Die Jungfrauengeburt in der Ascensio Isaiae’, in The Ascension of Isaiah, ed. J. N. Bremmer, T. R. Karmann and T. Nicklas; (SECA 11; Leuven: Peeters, 2016), 347–385.

[3] See Darrel D. Hannah, ‘The Ascension of Isaiah and Docetic Christology’, Vigiliae Christianae 53 (1999): 165–196 (181).