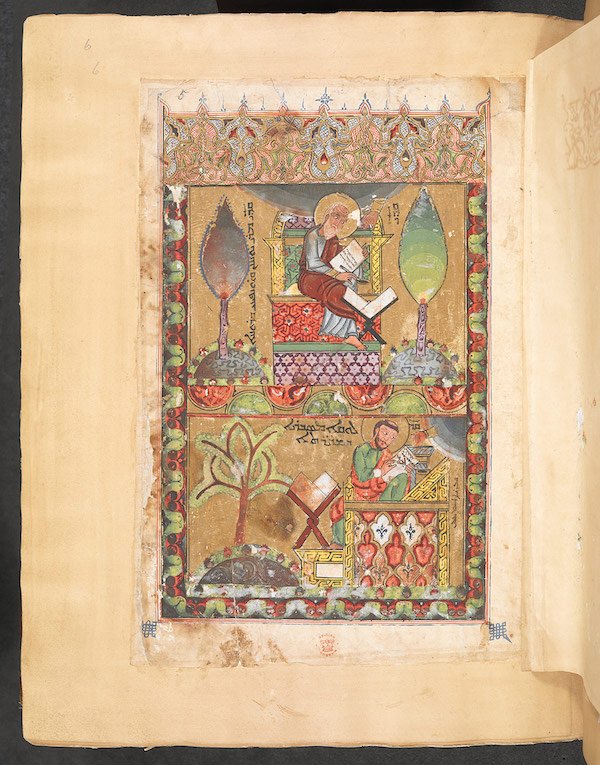

Syriac Gospel Lectionary, British Library Add MS 7170

The book under review is an outstanding and welcome contribution that informs and challenges key areas of scholarship on ancient texts.[1] It represents the culmination of years of work on the part of the author—an ongoing project that takes 2 Baruch as its point of departure. Though the author’s research on 2 Baruch has greatly illuminated our understanding of the Syriac version of that work, especially in its historical reception, her overall project has been more fundamental and much broader in scope. Its ambitions, which are epistemological and methodological, are nicely represented in the title of the book under review here, in which 2 Baruch comes last and the larger field of Textual Scholarship defines the middle part, but the driving inspiration for her project commands first attention: Invisible Manuscripts. This is what lies at the heart of Lied’s project: a determined commitment to challenge the attitudes and practices in textual studies that have produced a “general inattention… to manuscripts as cultural artifacts,”[2] rectifying that neglect through a kind of magic by which what was rendered invisible through active neglect is made to reappear before our eyes, through the author’s labors.

For scholars of ancient texts, nothing could be more objectively real in their disciplines than the physical objects bearing those texts. Yet it is commonplace for these artifacts to be so neglected, for the sake of extracting their texts, subjecting those abstractions to the rigors of textual criticism, and treating the resulting edited distillation in its disembodied form, so that the material objects rapidly fade from sight and become non-entities in our considerations. What Lied calls “a double obsession with origins”[3] dominates, by which scholars of ancient texts routinely ask, What can we know about the origin of this manuscript, so that we may know how to evaluate its worth as a witness to the (hypothetical) origin of this text? In this obsessive quest for (intangible) origins, not only do the (physical) objects themselves mysteriously fade, but origin-obsessed approaches tend to mute the testimonies of the communities of a manuscript’s actual use and reception, raising ethical questions about whom we are neglecting and why. Adopting the perspective and methods of what is sometimes called Material or (New) Philology, Lied has repeatedly shown us what a more “provenance aware” approach can add to our knowledge—pointing out blind spots, revealing hidden information, and resurrecting neglected, often minority voices. In this book, as in her previous work,[4] she coaches the reader not only to attend to manuscript artifacts as sources in themselves, but also prods the reader to attend to the communities who transcribed, preserved, and used a work as actually embodied in particular artifacts.

The aforementioned are the priorities that have characterized the author’s work for many years, and we see them in mature and splendid display in Invisible Manuscripts. Here the author pursues more fully all the main trajectories she had previously mapped in her research on 2 Baruch, bringing them together into a highly rewarding tour of a compelling interdisciplinary landscape. With the Syriac version of 2 Baruch as the central feature in this landscape, she ranges across an expansive terrain of issues, always coming back to the principal surviving embodiment of the work in the celebrated Syriac Old Testament[5] manuscript, the Codex Ambrosianus (Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, MS B21 inf. and B21 bis inf.). Throughout the journey, she engages several different fields, making substantial contributions to multiple lines of inquiry. My own interests lie in the areas of Syriac literature, the study of manuscripts, and the communities that used them. I also have great appreciation for the perspectives granted by material philology. In all these areas I find much to commend this well-researched and highly readable book. It exemplifies the application of methods for which the author has made frequent appeal, while also demonstrating the gains of doing so. In this review, I will focus on a few items, highlighting some delights I find in the study, discussing some areas where my judgment differs, and raising a question or two about what it all means.

First, by treating the manuscript as source, the author delightfully invites the reader to flip the standard approach to 2 Baruch as a text to be interpreted. Her survey of scholarship notices that 2 Baruch is routinely treated as a work of “apocrypha” or “pseudepigrapha,” a work whose origins probably lie in the late first or second century, composed in an effort to comfort Jews after the destruction of the Second Temple. However, this approach necessarily presumes a disembodied abstraction of the work as the object of study. In its principal embodied form, the Codex Ambrosianus, we are struck by the significance of the work’s placement. For one thing, its location (and liturgical use) in a Syriac Bible disrupts categories like “apocrypha” and “pseudepigrapha.” But also, building on the proposal that the sequence of books in Ambrosianus intentionally follows a “chronological biblical storyline,”[6] culminating in Josephus’ account of the Temple’s destruction, the author confronts us with an awkward reality: in its actual manuscript setting, 2 Baruch serves a storyline of deserved judgment against Israel and a tale of Jewish destruction—a dramatically different narrative frame for the work than the one dominating scholarship on 2 Baruch.

The resulting insight: an origins-oriented approach to 2 Baruch that seeks to place it into an ancient Jewish context—a situation for which we have no direct evidence—gives us one view of the work’s significance; the reception-oriented approach that respects its embodied form in a sixth- or seventh-century Syriac Christian manuscript gives us a different view. The former approach may be a worthy one, but scholars should admit that it relies on “the immaterial text… as ‘source;’” The embodied form of the text “turns out to be an Old Testament book in an Old Testament codex that uses temple destruction to argue the rejection of the old covenant.”[7] Yet in order to see this rather shocking reality, one must acknowledge the manuscript itself as source. While gently exposing the epistemic limitations of conventional scholarly perspectives on texts, the author also opens up such fruitful new avenues of research.

Another delightful feature in the book is its frequent turn toward communities of reception and use. The author examines closely the colophons of manuscripts and other indicators of ownership history, in order to trace their lives geographically. Her close analysis of the term ܗܘܓܝܐ (“study, meditation, vocalization”) in Ambrosianus’ donor note illuminates a range of possible significances the manuscript was seen to have in the eyes of the donor: as an object of “study,” an aid to oral “recitation,” or the material fulfillment of the life-giving command to “meditate” on the Law.[8] The discussion carefully considers a host of other clues pointing to reader engagement, in order to clarify how the books were being used, by whom, and in what situations. These analyses require correlating information about such things as Syriac book culture, paleography, the histories of particular monastic communities, the art and architecture of sacred spaces, considerations of canon, and liturgical practice as performative drama. The author’s portraits of devout monks working away in dimly lit libraries, or the Syriac faithful gathered in minority enclaves and chanting excerpts of 2 Baruch as part of their festive commemorations, are rich and compelling. Her discussion of a series of scribal notes in Ambrosianus leads convincingly to the conclusion that the manuscript was used as a source of excerpts for other, presumably lost, lectionaries and anthologies.[9] Her consideration of two lectionaries illumine the 13th-century reception of portions of 2 Baruch as part of the Old Testament in Easter Sunday celebrations.[10]

In short, the study repeatedly overturns the assumption “that the only historical context worth knowing when we study a writing is its time and place of origin,”[11] reminding us of other communities that deserve to be heard, not silenced through the collateral damage of methodological neglect. For the author, these are ethical matters. Obsession with origins can quickly lead scholars to neglect the intervening hands of those whose labors have “ensured the survival of the manuscript.” The author laments, “[w]hereas they have asked us to remember them, the priorities and practices of textual scholarship have pushed them into oblivion.”[12] The author strives to memorialize them, partly through the many overt and thorough analyses of their roles, contexts, and customs, but she also displays her respect in other, simple ways throughout the book. For instance, she formats quoted text according to its appearance in the manuscripts, preserving the column breaks. This is not an efficient way of quoting text, and we already have printed and digital facsimiles of the main manuscript available for inspection, but her manner of quoting reminds us that the forms bequeathed to us by scribes are part of the meaning. In another example, she admits her struggles in settling on a method for transliterating names, striving to balance the need to communicate clearly to readers with her desire to respect the cultural and linguistic heritages of the many owners and users of the manuscripts, whom academic conventions often render invisible.[13]

The book’s in-depth discussions involve a great many details that are subject to different interpretations, and the attempts to contextualize the book’s users require some degree of speculation in the synthesis of the data. The author acknowledges different viewpoints and engages them thoughtfully throughout the book. In a few areas the judgments of the present reviewer differ from those of the author. We will treat a less significant, text-critical matter first, before taking up an example of greater consequence.

In Chapter Four’s fascinating discussion of 13th-century liturgical engagement with 2 Baruch, the author draws attention to a textual variant in 2 Bar 73:2, where a lection excerpted from 2 Baruch (2 Bar 72:1–73:2) appears twice in the Syriac lectionary manuscript, British Library Add. 14,687 (fol. 157v–158r; 175v–176r). In Codex Ambrosianus, the text reads ܟܘܪܗܢܐ, “disease” (kurhānā; fol. 265r), i.e. the text promises, “disease shall withdraw.” But here the manuscript British Library Add. 14,687 reads ܟܘܪܢܐ (kurānā or kawrānā; fol. 158ra), i.e. “drought” or “heat,” yielding, “drought will be removed.” The difference is the omission of the single letter ܗ from the latter term; phonetically, the pronunciation of the two words is very similar. Furthermore, both senses fit the context. Lied says, “it is possible that ܟܘܪܢܐ is a scribal mistake,” but since “the same reading” occurs in both instances of the excerpt in British Library Add. 14,687, she concludes, “it is more likely that it reflects a different interpretation of the text.”[14] Stated this way, the point could be taken to imply that one choice excludes the other. Yet whereas I concur that both readings make good sense and that we should not let an obsession with defining “the original text” obscure the fact that real users of these embodied texts read and understood the passage differently—with “disease” vacating the scene for users of Ambrosianus, and “drought” doing so for users of the lectionary—nevertheless the transcriptional probabilities leave no doubt that these two readings are genetically linked. One derives from the other, in the (presumably lost) history of the development of the text, and the sort of scribal activity to which the author alludes with the phrase “scribal mistake” is very likely to be the cause, given the near synonymity of form and phonetics.

Without bothering over the question of which form was prior, we can simply observe that a transcriptional phenomenon, very possibly accidental, has triggered an instance of variance and produced two different streams of text-form, one of which supplies the text as we have it in the lectionary. Yet both streams present us with viable “interpretations,” to use Lied’s phrasing. However, in contrast to what she appears to be saying, I would contend that in the history of these readings, the proposed “different interpretation” is better understood as the result of the transcriptional phenomenon rather than its stimulus. Observing that each represents a “different interpretation” may get at the effect of the readings on readers, but probably not the cause of the variance. This may lie to close to the author’s thinking on the matter, but her brief discussion of it so focuses away from traditional text-critical considerations, and upon the interpretive function of the readings in the embodied text, that the latter is made to supplant the former as an explanation of the variance—whereas they should be seen as more complementary lines of discussion regarding its significance.

To be clear—the book’s handling of this variant is very brief and is not important to the author’s overall argument, but it illustrates a certain vulnerability in the book. Here as in other parts of the book, we may applaud the fervent enthusiasm for the embodied text, as well as the desire to chasten the obsession with origins that has dominated textual studies; but occasionally the book leaves reason to be concerned that the helpful and legitimate application of origins-oriented methods, such as the traditional techniques of textual criticism, may be over-shadowed. In view of the book’s purposes to honor a manuscript’s many contexts of use, the risk then is that some evidence attesting to users’ interactions with a text may be forgotten or misrepresented, even if in the current embodied form it is only an echo of a scribe’s past activity, as in this instance of variance.

A more consequential example of disagreement pertains to the author’s discussion of phenomena attached to the Prayer of Baruch bar Neriah (2 Bar 21; Ambrosianus, fol. 259r), one of the three prayers of Baruch rubricated with a title.[15] Building on the observations of others that the manuscript Ambrosianus shows signs of liturgical use, albeit infrequent,[16] and the evidence of 2 Baruch’s sparing but definite use in the aforementioned lectionaries, the author advances the hypothesis that the Prayer of Baruch bar Neriah was read from the actual pages of Ambrosianus within the context of a liturgical observance, probably the commemoration of the prophets.[17]

The case is well-argued and has much to commend it. One type of evidence to which Lied draws our attention consists of indicators that are not often treated as sources in textual studies, but should be: namely, traces of user interaction. These are clues left by active readers, constituting evidence of their interaction with and use of a book, e.g. thumbing, wax stains, erasures, and annotations. In typical practices of textual study and editing, this sort of evidence, along with such things as paratexts, garners little or no attention. This neglect can obscure what such evidence might have to tell us, especially about the purposes, reception, and users of actual books, in favor of presenting a disembodied text as the sole object of study.

Lied’s appeals to treat such trace evidence as a source are vindicated again and again in her study. Yet such evidence can be difficult to interpret with confidence, and in the instance of the Prayer of Baruch bar Neriah, our interpretations differ. The Prayer occurs on folio 259r of the Ambrosianus manuscript. At that opening of the manuscript (fol. 258v–259r), we find not only a rubricated title for the prayer made at the time of the manuscript’s production, but also multiple phenomena of later user interaction. The two that figure most prominently in Lied’s argument in support of the liturgical use of the manuscript here are: a cluster of wax stains on the bottom of fol. 258v, and an erasure in the top margin of fol. 259r, above the prayer. The concentration of wax stains invites us to speculate that readers paused over these pages specifically, reading the specially marked prayer in a dimly lit setting. This may have happened early or late in the manuscript’s history, or repeatedly, perhaps over many years, but the wax stains themselves do not say. As Lied laments, a campaign to conserve the manuscript in 2008 targeted wax stains along with other blemishes for repair, adding further obfuscation to the toll the years had already taken on the fragile evidence.[18] Perhaps in time such efforts as the Labeculae Vivae project, using advanced imaging to catalogue wax stains in medieval manuscripts, will shed more light on such things.[19] Meanwhile, the author is tentative, wisely acknowledging that the scenario of usage she proposes for the stains is speculative; yet I agree that she makes plausible sense of the evidence.

The erasure is another matter. At the top center of the page, in the margin above the prayer, we find plain signs of erasure. Many erasures and corrections occur in Ambrosianus—what is the import of this one? From the digital images available online,[20] this reviewer cannot make anything out of the erased text. As the author says, advanced imaging might help one day. But she has examined the manuscript directly and can make more of it out,[21] offering a handful of reconstructed letters in broken sequence, being confident of only one or two letters: an initial -ܕ (possibly “of”) and a subsequent medial -ܝ-.[22] She hypothesizes the word ܕܢܒܝܐ (“of the prophet/s”), though this can only be a portion of what was once present; other letters or ornamentation must have been erased also.

As for the function of the missing text, the author offers two hypotheses. The first is that the text had been part of a running title. The location on the page matches the placement, size, and ink color of other running titles, such as those recurring in quires 1–22 and 31–3. of the manuscript Also, its occurrence on the first page of a new quire fits the pattern—in this case the quire marked ܟܚ (28). However, the other quires 23–31 of the manuscript lack such running titles, so this one would be out of place in that regard. Nor is it obvious what a heading corresponding to the contents of this quire might have read, given the possible letters. But perhaps it had been put on that page by mistake during the early stages of the quire’s production, and should therefore not be expected to match the contents, and was subsequently erased because of the mismatch.

In the view of this reviewer, the latter hypothesis provides the best explanation, by far. Even the one certain letter, an initial -ܕ, would make the heading parallel to what we find in many of the other titles on recto leaves of the manuscript (e.g. “Book / of Job the Righteous” [fol. 63v-64r], and “Book of Joshua bar Nun” [fol. 68v–69r]). Formally, the erasure fits the profile of a running heading very well—even if we are left to wonder what it originally said and why it was erased. Yet Lied goes on to offer a second hypothesis in which she appears rather more invested: that someone had used the upper margin to mark the prayer for liturgical use, so that this piece of trace evidence strengthens her case not only that this portion of the text of 2 Baruch had been used liturgically, but that users opened this very manuscript to this location and employed this part of the manuscript in liturgical activity.[23] She points out that the manuscript acquired a number of liturgical notes in its margins, and that some of these notes also begin with -ܕ. Some of these were written at or near the production stage of the manuscript and some were added much later. They include readings for the commemoration of prophets, that could help us contextualize the reading of this particular lection from 2 Baruch.

The author’s discussion of the manuscript’s layers of liturgical notes implies strongly that they are analogous to the erased note, so that it becomes easy to imagine it as one of them. Indeed, some of the other marginal liturgical notes also occur near rubricated sections of text, and a few are written in red ink too. However, even these notes are written, not in the top margins, but beside the column of text and in very close proximity to the start of the lections. Furthermore, these other notes, written by different scribes at different times, are all written transversely, i.e. vertically and at right angles to the main text (e.g.ܕܦܢܛܝܩܘܣܛܝ , “for Pentecost;” fol. 42v)—even where the outer margin provides ample room for horizontal notation (e.g. ܩ ܙܕܝܩܐ; fol. 177v). One might wonder why such notes would be written vertically, if not strictly due to space constrictions. For the reader, such oblique bodies of text are less disruptive to the horizontal text lines in such a fine volume as Codex Ambrosianus, and they respect the subordinate nature of the notes, most of which are written with less precision and elegance as the main text. But also, many Syriac scribes had the habit of writing vertically, at right angles to the usual reading perspective, tracing the words vertically.[24] Once the gatherings were bound in place, given the normal reading orientation of this massive book, we are not surprised that scribes would compose notes in this fashion and create what we see over and over in Ambrosianus: annotations in the side margins, at right angles to the main text, for this would require no reorientation of the manuscript on the desk as they read and wrote. Yet this is all very unlike the erasure in question, i.e. a note written in the top margin, not at the sides; in the upper center and not so close to the text alleged to be its subject; in a direction evenly parallel to the main text, not oblique to it. Whereas we are at a loss to find something analogous to this amongst the other liturgical notes, we have many parallel instances featuring all these characteristics among the running titles.

Lied is appropriately cautious: “The nature of the evidence is too incomplete to draw any firm conclusions,” she says.[25] Yet she seems more confident in the hypothesis that the erased note was liturgical, a view that has little to commend it, in my judgment. I think it much more likely that it was a running title, albeit misplaced. This is also a more plausible reason for its erasure, as a mismatched heading (i.e. mismatched to the contents of the quire for some reason), rather than as a liturgical note erased because the lection eventually “fell out of use,” as Lied suggests.[26] The latter is not a very satisfying explanation of the erasure, considering how many potentially redundant notes were retained in the manuscript. So, whereas it is true that, “the rubricated Prayer of Baruch bar Neriah, the partly erased note in the upper margin and the clustered wax stains all appear in the same opening of the codex,” as Lied observes,[27] and I agree with her that we have some indications that the Prayer was read liturgically, perhaps even in this embodiment of the text, the erasure itself does not support this particular scenario of user interaction.

The foregoing evaluation of areas of disagreement may seem to be focused too obsessively on very small details. To this potential criticism I offer a rejoinder and a pair of affirmations. First, a great many of the book’s arguments rely upon the interpretation of tiny details—some of which are so “small” that they typically (and sadly) fall beneath the notice of many studies. So it is not inappropriate for us to look at her discussion of them closely. The book’s liberal supply of printed digital images and references to online resources enable readers to check things for themselves. Indeed, the author’s manner of argumentation is very transparent and her presentation generously welcomes this sort of engagement, a quality that distinguishes Lied’s scholarship generally. Nevertheless, the present reviewer must affirm that the particular details that are in focus here are not lynch-pins in her overall arguments. One suspects that a certain interpretive bias has predisposed the author to interpret the details in the way she did, but it must be acknowledged that the differing judgments offered here do not jeopardize the book’s major proposals. Furthermore, the reviewer wishes to confirm that these are exceptions, and he finds himself nearly always in agreement with the author’s judgments about Syriac paleography, codicology, and her handling of the Syriac texts. So we are indebted to Lied for her assiduous attention to details; she shows us not only how much more information there is to recover and how many more sources we already have at our disposal, if we will only be attentive; but her constructive handling of those data and her synthetic interpretations of the details, especially in their combinations and interactions, present us with a model for doing this sort of work.

By the end of the book, many readers will be left applauding the author’s methods and her results, convinced that we are in a far better position to imagine the persons who used these embodied forms of 2 Baruch and the communities of practice in which they lived and worked and worshiped. Furthermore, readers may find that they have been persuaded by the author’s appeal, challenging the methodological and epistemological presumptions underlying prevalent practices. The book’s manner of argumentation and the constructive results leave one eager to imitate the methods exemplified in it, treating the manuscripts themselves as sources, not mere “witnesses” to sources. The reader may be struck by what these methods have accomplished for our understanding of 2 Baruch and the contexts of its past readers, at the same time causing us to reevaluate the scholarship on that work! Yet when one contemplates turning to other works in other manuscripts, or even to other works within the Ambrosianus manuscript, one may wonder how to transfer the approach. Although Lied’s study is as much about the manuscripts and their contexts of use as it is about 2 Baruch itself, the latter work provides the constant focal point, or center of gravity, in relation to which she analyzes all the data and synthesizes constructive conclusions. The fact that we have so very few surviving embodiments of 2 Baruch may be occasionally frustrating to the author, but in the main this sparsity enables the discussion, without over-complicating it. Both the work of 2 Baruch and its material contexts are indispensable to her, as she seeks to explicate the relationships between them.

But what about works that survive in more material artifacts—perhaps many, many more artifacts? If one were to take another work, say the book of Isaiah, what challenges do we face in applying a highly “provenance aware” approach? We have the embodiment of Isaiah in Ambrosianus to consider, and that might make a suitable study in itself. But if we wished to correlate other embodiments of this work, whether whole or partial, in Bible manuscripts, lectionaries, and catenae, in order to approximate the richness of Lied’s study of the embodiments of 2 Baruch—even if we were to confine ourselves just to the Syriac versions of Isaiah—we would quickly find ourselves swimming in deep waters, with a veritable tidal wave of varied manuscripts and possible contexts of use piling up and threatening to overwhelm us. At that point, it might be tempting to return to the study of the disembodied Isaiah and its reception, since that is a simpler object. Or perhaps to go the other direction and just study the manuscripts as artifacts, a kind of codicological study, perhaps with greater sensitivity to questions of reception of the codices, but without much focus on Isaiah specifically. Is it possible to manage these tensions in cases where the body of relevant evidence seems far less manageable? This reviewer can scarcely imagine attending to all the embodiments of Isaiah over the span of some centuries—but perhaps that would be beside the point. And if we wished to recruit to this cause scholars interested in the reception of Isaiah, how might we lure them into sharing this task with us, when they have so many other more definite and accessible sources for the reception study of Isaiah to which they must surely attend—such as Basil, Cyril of Alexandria, and ibn Ezra, just to begin what could be a very long list of historic interpreters?

With 2 Baruch, we have so little to hand, we are quick to welcome the expansion of sources that Lied’s approach affords us. But if we were to amend our ways and quit neglecting the artifacts and their readers generally, how might that transform our approach to works for which the embodiments are exponentially more numerous than for 2 Baruch? Or is it inevitable that the fruit of such studies would be less tied to specific works, as in the hypothetical case of Isaiah? Lied’s book effectively evangelizes for its cause; on finishing it, one may feel compelled to “go and do likewise.” Hence, we may invite her to cast more light on the way forward, so that we may have a clearer sense of what she hopes her book will prompt in those of us who wish to apply the same methods in areas of textual study for which the artifactual evidence is more voluminous.

Jeff W Childers, Graduate School of Theology, Abilene Christian University, Abilene, Texas (childersj@acu.edu)

[1] I am appreciative of the opportunity to participate in the review panel devoted to this book in the Pseudepigrapha session of the Annual Meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature (23 November 2021) and gladly acknowledge my debt to the participants, especially the other panelists and author, for helpful discussion contributing to the refining of this review.

[2] Liv Ingeborg Lied, Invisible Manuscripts: Textual Scholarship and the Survival of 2 Baruch (Studien und Texte zu Antike und Christentum 20; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2021), 1.

[3] Lied, Invisible Manuscripts, 79.

[4] The book contains a full bibliography of Lied’s work in this area, along with helpful orientation to other scholarship in Material Philology.

[6] Lied, Invisible Manuscripts, 60.

[7] Lied, Invisible Manuscripts, 77.

[8] Lied, Invisible Manuscripts, 106–07.

[9] Lied, Invisible Manuscripts, 129–34. The author acknowledges her reliance on Grigory Kessel for this interpretation of the markings. Lied’s discussion does not satisfactorily explain the scribes’ or editors’ use of Ambrosianus as a source for these excerpts. The clear identification of texts to be excerpted indicates reliance on a source other than Ambrosianus, a suspicion reinforced by the matching lections occurring in manuscripts such as British Library Add. 14,687. The identified lections are fairly precise. If the scribes’ identification of these passages was being guided by an existing collection of lections, why not use the latter as the exemplar? That would surely have been more efficient than turning to various contexts in the great pandect, marking and copying them. Was it the age and prestige of Ambrosianus that motivated them to rely on it directly as their textual source? Further consideration of such questions would be welcome.

[10] See especially Lied, Invisible Manuscripts, 174–85.

[11] Lied, Invisible Manuscripts, 144.

[12] Lied, Invisible Manuscripts, 110.

[13] See Lied, Invisible Manuscripts, 31.

[14] Lied, Invisible Manuscripts, 155. One of the aforementioned scribal notes directing someone to “copy here…” occurs in the margin adjacent to the beginning of this passage (fol. 265r), a passage which shows up twice in British Library Add. 14,687. However, I agree with Lied’s argued conclusion that we should not take Ambrosianus as the exemplar of that lectionary, despite the overlap between marked portions of Ambrosianus and lections that we find in British Library Add. 14,687; instead, “[t]he inscription of the ܟܬ notes in the codex may have been part of the preparation for the copying of a lectionary manuscript that does not survive but that displayed similarities to the selection and order of lections in Add. 14,686 and Add. 14,687” (Lied, Invisible Manuscripts, 132). There is no indication that the lections in British Library Add. 14,687 were transcribed directly from Ambrosianus.

[15] Lied, Invisible Manuscripts, 138.

[16] Lied, Invisible Manuscripts, 120–24.

[17] Lied, Invisible Manuscripts, 139.

[18] Lied, Invisible Manuscripts, 114–15.

[19] See Alberto Campagnolo, Erin Connelly, and Heather Wacha, “Labeculæ Vivæ: Building a Reference Library of Stains for Medieval and Early Modern Manuscripts,” Manuscript Studies 4 (2019): 401–16; available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/mss_sims/vol4/iss2/7; see also the blog of the Library of Stains project: “Labeculae Vivae: Stains Alive,” accessed 20 December 2021, at: https://labeculaevivae.wordpress.com.

[20] For the link to the image, see reference in Lied, Invisible Manuscripts, 134.

[21] Lied acknowledges that she was also able to get the assistance of Lucas van Rompay in reading the note (Lied, Invisible Manuscripts, 134).

[22] Lied, Invisible Manuscripts, 134.

[23] Lied, Invisible Manuscripts, 137–39.

[24] William Wright noticed this—see Wright, Catalogue of the Syriac Manuscripts in the British Museum Acquired Since 1838 (London: Trustees of the British Museum, 1872), 3.xxvii. Adam McCollum draws attention to an amusing demonstration of this, involving a “pendulous pot,” or lamp, in the Lebanese Maronite Missionary Order, MS 103 (LMMO 00103, fol. 159v); see Adam McCollum, “A Pendulous Pot,” in hmmlorientalia (2 December 2011), accessed 20 December 2021, https://hmmlorientalia.wordpress.com/2011/12/02/a-pendulous-pot.

[25] Lied, Invisible Manuscripts, 139.

[26] Lied, Invisible Manuscripts, 139.

[27] Lied, Invisible Manuscripts, 138–39.