Brad Boswell, Cyril against Julian: Traditions in Conflict (Ph.D. Dissertation, Duke University 2021).

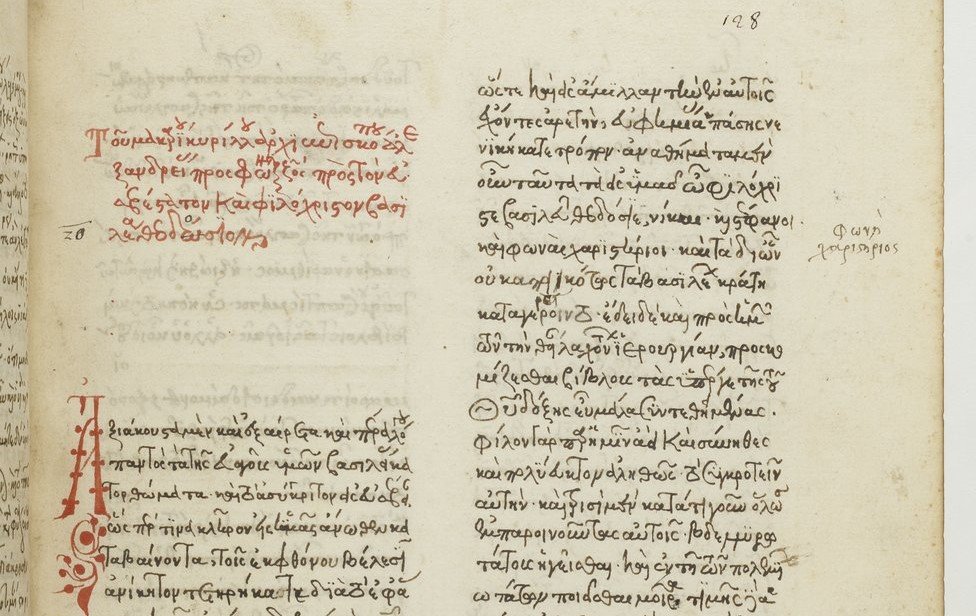

When the Roman Emperor Flavius Claudius Julianus—better known to many as Julian the Apostate—perished on a Persian battlefield in 363 CE, his efforts to turn back the tide of Christianizing efforts within the Roman Empire died with him. In the final decades of the fourth century, subsequent Christian emperors only further solidified the political and social status of Christianity. Julian’s intellectual challenges, however, lingered. In the 420s, Cyril, the new bishop of Alexandria, sensed a need to compose a colossal response to one of Julian’s final compositions, the anti-Christian Against the Galileans. My dissertation is a study of Cyril’s little-examined and untranslated text, known as Against Julian, and of the intellectual conflict that he and Julian engaged.[1]

The polemical texts, as often happens, seem initially ill-suited to interpretation as advancing genuine intellectual engagement. Wide-ranging in their contents and arguments, both resist coherent explication and invite instead readings as disconnected and vitriolic barrages with minimal organization, design, or intellectual substance. As one study of Against the Galileans concluded, Julian delivered “a hodgepodge of accusations, specious arguments, sarcasm, unargued propositions, adventitious allusion, and special pleading.”[2] The text seems to invite (and has received) analysis that treats the disagreement as mere rhetorical contest over cultural power or identity formation—engagements intelligible on terms that reduce religious commitment or substantive theological and philosophical claims to epiphenomenal status.[3] The same might be said of Cyril’s response.

But it need not be, for either text. Without denying Julian’s and Cyril’s equally shared aspirations to cultural authority or the political dimensions of their religious claims, my study treats Julian and Cyril as representatives of strong traditions of life and thought, whose texts engage in substantive disagreements with rivals. To do so, I draw from the work of contemporary philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre.[4] Best known as one of the twentieth century’s foremost ethicists, MacIntyre’s analysis of intellectual engagement between strong traditions provides the hermeneutic heuristic needed to make sense of Julian’s and Cyril’s texts: narrative conflict. Key to MacIntyre’s contributions is the insight that the maximal framework of intelligibility for a tradition is a narrative—a story by which a community makes sense of its own history, its practices, and the very words it uses to understand itself and its place in the cosmos. For MacIntyre, rationality itself takes distinctive shape from the narrative of a tradition. Reasoned disagreements between traditions are, crucially, thus “always in key part differences in the corresponding narrative.” Depending on how little different traditions’ standards of reasoning are shared, such disagreements might be intelligible only at the level of corresponding narratives. In such clashes, suggests MacIntyre, “that narrative prevails over its rival which is able to include its rivals within it,” demonstrating the ability to “retell their stories as episodes within its story.”[5] Such was Julian’s task in Against the Galileans and Cyril’s in Against Julian: both sought to demonstrate the superior explanatory power of their respective tradition’s maximal hermeneutic narrative by reinscribing “episodes” from their rival’s story within their own.

Neither treatise is narrative in genre, and much of my project is given to demonstrating how the wide-ranging engagements over Abraham and Plato, cosmogony and providence, animal sacrifice and baptism, etc. make sense as part of larger rhetorical and intellectual projects of out-narrating an opponent. The first chapter opens with an illustrative case study of narrative conflict, focusing on Julian’s and Cyril’s competing and confident interpretations of an exceedingly vague biblical text. It then explains MacIntyre’s conceptual apparatus of traditions, rationality, and narrative, and how this framework raises questions about translation and (in)commensurability between rival traditions. It concludes by introducing the details of Julian’s and Cyril’s contexts and texts and the relevance of this study to scholarship on late antiquity. The second chapter is entirely devoted to a comprehensive, narrative-conflict analysis of Julian’s Against the Galileans, the rhetorical heft of which has regularly been overlooked by Julian’s modern readers. Chapters three through five focus on Cyril’s arguments in Against Julian, with chapter three tracing key features of the narrative backdrop to Cyril’s arguments, and chapters four and five focusing on clusters of renarrated “episodes.” Chapter four examines several that are broadly categorizable as “cosmological,” including the events and agents of creation, as well as the texts that relate them and their authors. Chapter five is organized around Julian’s own category of the “gifts of the gods” and traces Cyril’s renarration of a loose clusters of “episodes”: exemplary characters in the traditions’ histories, examples of intellectual superiority, and the details of political dominion. These two chapters broadly track how Cyril rebuts Julian’s attempts to subsume features of the Christian narrative within the Hellenic narrative and how he simultaneously dislodges “episodes” from Julian’s narrative and re-explains them on Christian terms. The concluding chapter introduces Cyril’s Against Nestorius as a point of comparison with Against Julian. The distinct features of Cyril’s inter-tradition conflict with Julian stand out even more clearly against the backdrop of the striking formal similarities between Against Julian and Cyril’s other, equally polemical text that pursues intra-tradition conflict against his fellow Christian bishop, Nestorius.

My study concludes by returning to larger questions about the possibility of mutual understanding and translatability across traditions engaged in narrative conflict. The implications for our understanding of Julian and Cyril, as well as the ancient traditions they represented and maintained, are enormous. But the implications extend further still, as should be clear from my concluding list of possible indicators that suggest narrative conflict may be at play between rival traditions, past or otherwise. The phenomenon of narrative conflict, after all, is not cabined to the ancient world.

[1] Robert L. Wilken wrote in 1999 that “In any list of the most unread major works of early Christian literature

Cyril's Contra Iulianum would stand close to the top, if not at the summit.” Thanks largely to the publication of a critical edition in 2016-17, the situation is rapidly changing. English, French, and German translations are all currently underway, and the spate of conference panels and papers around the world on Against Julian in recent years suggest further studies to come. For Wilken’s comments, see “Cyril of Alexandria’s Contra Iulianum,” in The Limits of Ancient Christianity. Essays on Late Antique Thought in Honor of RA Markus, (eds.) William E. Klingshirn and Mark Vessey (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1999), 42–55. The critical edition is by Christoph Riedweg, Christoph, Wolfram Kinzig, and Thomas Brüggemann (eds.): Kyrill von Alexandrien: Gegen Julian, 2 vols, GCS, N.F. 20–21 (Boston: De Gruyter, 2016–2017).

[2] R. Joseph Hoffmann, Julian’s “Against the Galileans” (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2004), 84–85.

[3] See, for example Susanna Elm’s treatment of Julian and Gregory of Nazianzus in Sons of Hellenism, Fathers of the Church: Emperor Julian, Gregory of Nazianzus, and the Vision of Rome (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012). After an otherwise insightful and probing comparative study of these two figures, their peers, and their religious and philosophical commitments, she concludes that “Indeed, though they exercised power to different degrees, all the principals of this book (most of whom were bishops) had one dominant concern: how to govern the oikoumenē of the Romans the right way” (479-80).

[4]A close analogue of my study is C. Kavin Rowe’s One True Life: The Stoics and Early Christians as Rival Traditions (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016). Rowe pioneered the use of MacIntyre for ancient historical study, and the scholarly reaction to One True Life demonstrates the field-shifting potential of MacIntyre’s work on inter-tradition relations—see, e.g., the edited volume from leading scholars in response to Rowe’s study: The New Testament in Comparison: Validity, Method, and Purpose in Comparing Traditions, (eds.) Barclay, John M. G., and B. G. White (London: T & T Clark, 2020). My study, focusing on material from several centuries later, deploys and assesses MacIntyre’s theory with figures more suited to his focus. The characters at the center of One True Life (Luke, Paul, Justin Martyr; Seneca, Marcus Aurelius, Epictetus) are not engaged in overt inter-tradition polemics, and thus Rowe’s task of explicating the relationship between the earliest Christian movement and the Stoics relied on an imagined juxtaposition. My study considers open and explicit disagreement by a focused analysis of two characters.

[5] Alasdair MacIntyre, Three Rival Versions of Moral Enquiry: Encyclopaedia, Genealogy, and Tradition (South Bend, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1991), 80–81.

Brad Boswell completed his Ph.D. from the Graduate Program in Religion at Duke University in 2021 and is currently a Postdoctoral Research Associate with the Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies at Princeton University.