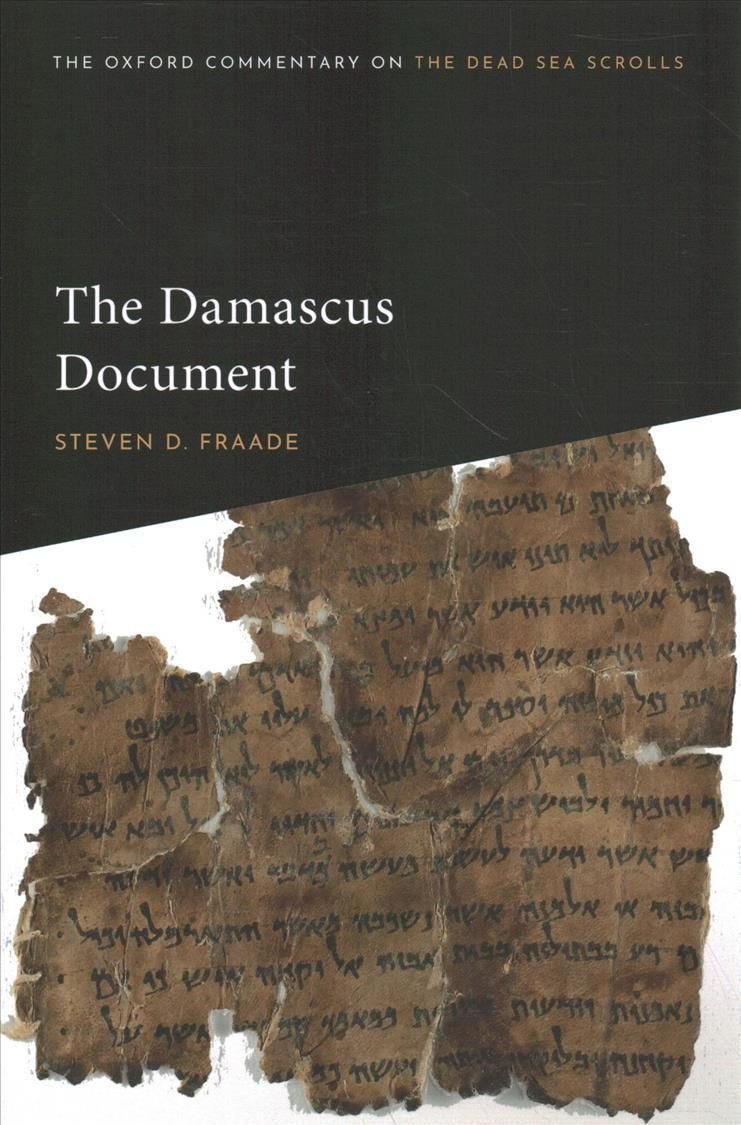

Fraade, Steven D. The Damascus Document, Oxford Commentary on the Dead Sea Scrolls. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021.

When students set out to study the Dead Sea Scrolls, they usually have to rely on composite editions, such as the two-volume Dead Sea Scrolls Study Edition, which conveniently collects Qumran texts and translations.[1] However, students might find it difficult to make sense of the non-biblical texts due to the lack of notes and explanations in these editions. If the hope is to use the Scrolls to shed light on other corpora, readers often need to look for connections by themselves. Fortunately, the recent publication of several rigorous yet accessible reference works is making the Scrolls increasingly accessible to students and scholars of cognate fields. The Damascus Document, the second volume in the series, Oxford Commentary on the Dead Sea Scrolls (OCDSS), is such a work that will be helpful to both new readers and experts.

Written by Steven Fraade, Mark Taper Professor Emeritus of Religious Studies at Yale University, this critical commentary consists of two main parts: “Introduction” (pp. 1-22) and “Texts, Translations, Notes, and Commentary” (pp. 23-155). A select bibliography (pp.157-72) and indexes of ancient sources, modern scholars, and subjects (pp.173-89) follow.

In the introduction, Fraade provides an overview of the basic information about the Damascus Document, including the discoveries of CD and the 4QD manuscripts and the relationship between them, the various names and dating of the Damascus Document, and the identity of the author(s) and audience. In general, Fraade summarizes the scholarly theories and provides succinct comments on the merits and weaknesses of each. The latter half of the introduction situates the Damascus Document in relation to several important topics in Second Temple Judaism, such as the development of Jewish law, the leadership of the sect, and the formation of the Hebrew Bible. Two traits of these sections are worth mentioning. First, Fraade highlights the value of bringing the Damascus Document into conversation with other Second Temple texts and early rabbinic writings, but he also warns against possible misuses of the comparative methods. For example, he consciously avoids referring to the rules in the Damascus Document as Qumran hălākâ, “lest a direct line of continuity be assumed, rather than established… between Qumran mišpāṭ and rabbinic hălākâ” (p. 8). Second, drawing on Walter Benjamin and Mikhail Bakhtin’s insights on the after-history of texts, Fraade calls for more attention to the performative reception of the Damascus Document. This approach resists pinpointing the Damascus document to a specific time of origin, but sees it as a collection of “scripts” which were performed over time in specific social settings, such as ceremonial recitations and/or communal study (pp. 9-10).

The translations and commentaries cover both the CD and 4QD fragments, and the text is presented in 54 topical units. (A helpful guide to the layout of texts, translations, and commentaries, which also discusses Fraade’s use of editions and translations of other scholars, can be found on pp. 20-21.) Each unit consists of the Hebrew text, translation, notes, and comments; some units also include suggestions for “Further reading” before the notes. The Hebrew text generally follows the edition of Elisha Qimron for CD and the edition of Joseph Baumgarten for 4QD, although Fraade occasionally adapts their reconstructions.[2] When other manuscripts parallel the text under discussion, they are specified in parentheses in the topical heading of the unit; textual variations are noted only when they are consequential to the textual meaning. Fraade translates the Hebrew text in accessible and smooth prose, and when the Hebrew text is too laconic, he inserts explanatory phrases in parentheses. For instance, when translating the Hebrew expression ואם ישבע ועבר in CD 15:3, Fraade adds the object of the two verbs in parentheses and renders it as “and if he swears (an oath) and then transgresses (it)” (p.74). Biblical citations in both the Hebrew texts and the translations are set in bold.

In general, the textual notes of this commentary focus on elucidating obscure expressions and pointing out the interconnections between the text and other Scrolls or other ancient texts. Unlike the first volume of OCDSS on 1QpHab, one does not need knowledge of Hebrew to follow the notes. When it is necessary to clarify the editorial history of the text, Fraade succinctly summarizes various proposals, provides even-handed evaluations, and points the reader to relevant literature for further reading. When multiple interpretations are available, Fraade discusses which interpretation he follows and lists bibliographies for other renderings. Each topical unit concludes with a paragraph of comment, which explains the meaning and significance of the unit as a whole. For non-expert readers, the comment can serve as an introduction to its corresponding unit. For example, in his comment to the unit of CD 10:14-11:18, which contains a list of Sabbath laws, Fraade makes two general observations. First, whereas the Hebrew Bible lacks explicit stipulation of prohibited labor, the Damascus Document contains “one of the earliest topical clusters of Sabbath rules with regard to forbidden work” (p. 102). Second, this list can be fruitfully compared to relevant reports on Sabbath observance in a number of Second Temple Jewish texts and the New Testament (pp. 102-3). Interested readers are then guided to look at the notes for detailed discussions and further references.

An extensive bibliography follows the body of the commentary. In addition to modern scholarship on the Damascus Document and related topics, the bibliography contains extant textual editions, translations, lexical tools, and websites of manuscript photos. The index to ancient sources will be welcome among readers from cognate fields, especially the New Testament and rabbinic literature. Among recently published commentaries on the Dead Sea Scrolls, this volume provides one of the most extensive indices in terms of relevant passages to these two corpora.[3]

Fraade’s commentary is of value to readers from different fields in academia. Students of the Dead Sea Scrolls will find this book to be a helpful guide to both the Damascus Document and many larger topics of the field, which Fraade evaluates in a balanced way and for which he provides bibliographies. Students will also benefit from the “Further reading” sections in the body of the commentary. For example, on CD 4:12-5:15, a section which describes the history of Israel as under the rule of Belial, Fraade provides an introductory bibliography on three topics in his “Further reading” section: calendrical disputes in ancient Judaism, Levites in the Hebrew Bible and ancient Judaism, and the expression “end of days” (p. 46). Such notes will allow students to quickly expand their knowledge of relevant topics as they work through the text.

For experts in cognate fields, this commentary is a useful reference work to the Damascus Document. This volume conveniently includes the Hebrew texts of CD and selected fragments of 4QD in one small volume. Compared to Ben Zion Wacholder’s commentary, the other major running commentary on the Damascus Document (Wacholder names this text The Midrash on the Eschatological Torah or MTA), Fraade’s notes and commentary are more concise and accessible. Readers will also find Fraade’s interpretations to be more balanced in contrast to those of Wacholder, who adopts a controversial interpretative framework for his readings.[4] Moreover, as one of the leading scholars studying the Scrolls with the comparative method, Fraade constantly draws connections between the Damascus Document and other early Jewish texts in his notes. For example, Fraade’s note to CD 11:17, which discusses the issue of saving human lives on Shabbat, points to relevant passages in 1 Maccabees, Josephus, Halakhic Midrash, the Babylonian Talmud, and the New Testament (pp. 101-2). These notes, along with the index of ancient sources, will be an invaluable resource to anyone who wishes to situate the Damascus Document in larger social and religious contexts.

Fraade’s balanced and succinct style of commentary is congruous with the mission of the Oxford Commentary on the Dead Sea Scrolls series— “to provide scholarship of the highest level that is accessible to non-specialists.” The commentary is a product of and testament to the author’s meticulous use of the comparative method and will surely contribute to conversations between scholars of Scrolls and specialists in cognate fields.

Tianruo Jiang is a Ph.D. student in Early Mediterranean and Western Asian Religions at Yale University. He may be reached at tianruo.jiang@yale.edu.

[1] Florentino García Martínez and Eibert J.C. Tigchelaar, eds., The Dead Sea Scrolls Study Edition, 2 vols. (Leiden: Brill, 1997).

[2] Elisha Qimron, The Damascus Document Reconsidered (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society: Shrine of the Book, 1992); Joseph M. Baumgarten, Qumran Cave 4. XIII: The Damascus Document (4Q266-273), DJD 18 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968). Fraade also consults the composite edition of Elisha Qimron, The Dead Sea Scrolls: The Hebrew Writings, vol. 1 (Jerusalem: Yad Ben-Zvi, 2010), 1–58, xxi–xxiv.

[3] Fraade’s index lists 28 relevant New Testament passages and more than 130 relevant rabbinic passages, which follows and expands on a trend found in similar commentaries on the Dead Sea Scrolls, such as Ben Zion Wacholder, The New Damascus Document: The Midrash on the Eschatological Torah of the Dead Sea Scrolls: Reconstruction, Translation and Commentary (Leiden: Brill, 2007), 403-425; Charlotte Hempel, The Community Rules from Qumran: A Commentary (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2020), 323-340.

[4] Wacholder, The New Damascus Document, 3-17. Wacholder argues that the Damascus Document was composed by a single author, Zadok, in the third century BCE, and his translation and interpretations are informed by this position. For a detailed discussion of Wacholder’s interpretative framework, see Gregory L. Doudna, review of The New Damascus Document: The Midrash on the Eschatological Torah of the Dead Sea Scrolls: Reconstruction, Translation and Commentary, by Ben Zion Wacholder, Review of Biblical Literature 11 (2009): 257-262.