“If therefore, when you have opened any one whatsoever of the four Gospels, you might wish to attend to any chapter you choose, to know who has said similar things and to find the distinct passages in each…”[1]

“A rich indetermination gives them […] the function of articulating a second, poetic geography on top of the geography of the literal, forbidden or permitted meaning. They insinuate other routes into the functionalist and historical order of movement.”[2]

I am grateful to each of my interlocutors in this forum for their generous engagement with Eusebius the Evangelist.[3] In what follows, I structure my response around three themes: (1) technologies and practices, (2) readers, and (3) imagination. These three themes interweave with one another as we consider how Eusebius’s reconfigured Gospel “articulat[es] a second, poetic geography on top of the geography of the literal.”[4]

1. Technologies and Practices

Technology is a framing concept in Eusebius the Evangelist. But what do I mean by “technology”? As Amsler notes, my focus is not simply on material devices—the codex, say, or the microchip. Indeed, I would suggest that scholars of early Christianity have focused too much on the codex, at the expense of other late ancient technological and epistemological developments.[5] I focus on conceptual technologies—in particular, the table of contents and the column-and-row table.

Eusebius deployed these emergent technologies to invite use, to guide the reader to particular practices of navigating Gospel text. In combination with my central methodological approach to meaning as use,[6] the book builds upon the insights of historians of science—especially Thomas Kuhn and Michael Polanyi—who argue that knowledge is made and who attend to the material conditions, social contexts, and varied practices that both afford and limit the possibilities of knowledge.[7] Technologies are not just about what’s possible, but about what is made convenient, practical, and obvious. Hence the focus on use. Technologies and practices are intertwined. Arguments about meaning and knowledge are about what people do. Eusebius’s project invites readers to put it to work. As I demonstrate in Eusebius the Evangelist, readers put it to work in enormously variegated ways, far more than Eusebius himself might have imagined.

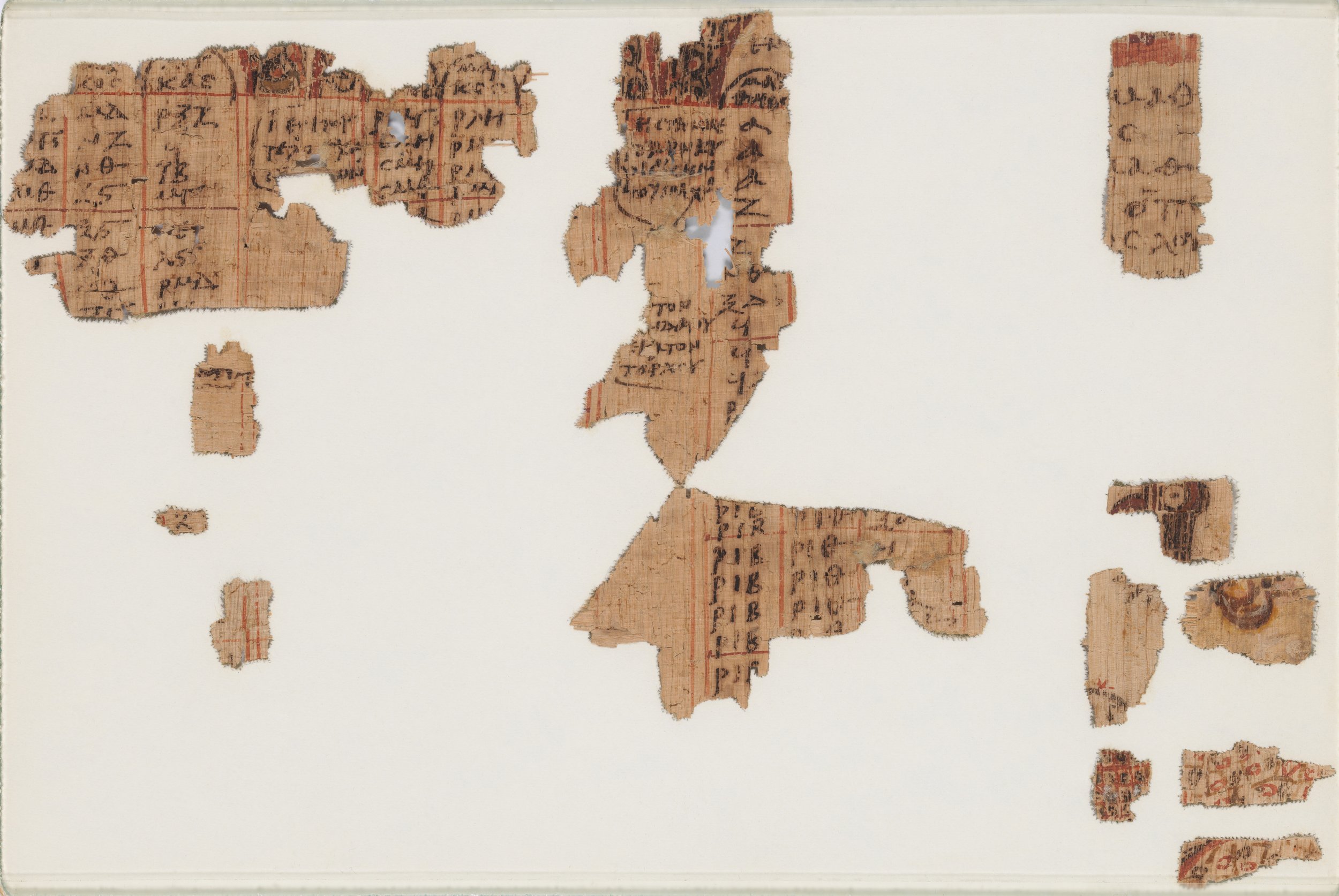

In this light, I turn to the material formats in which Eusebius’s innovative system might have appeared. Dilley notes that Eusebius’s reference tables might have been compiled using other media formats—perhaps the ubiquitous wax tablet or the parchment notebook. Such “erasable media” are widely attested in late antiquity as formats that lend themselves to work-in-progress. (Here Amsler’s points about the planning and preparation involved in Eusebius’s crafted intertextual fabric, textus, strike me as perceptive and apropos.) This seems entirely plausible to me—although we don’t have direct evidence. Dilley is right that there is no technological reason for Eusebius’s canons to be codex-dependent. Moreover, there are pragmatic reasons to imagine that the draft-work might have been done in a medium more forgiving than ink-and-papyrus.

This intersects with another point that is both historically and ethically significant: We often imagine projects like those of Origen and Eusebius as “solo-authored.” But that is seldom, if ever, true. (I’m grateful to Pragt for mentioning this!) The material conditions of Eusebius’s project are opaque. But we shouldn’t assume that we have to do with a singular genius. Certainly, Eusebius builds upon the work of predecessors. This is part of what I argue in putting Eusebius into broader histories of Gospel rewriting. But it’s also important that Eusebius may have relied on the work of other, uncredited collaborators. This is certainly the case for his Caesarean predecessors Origen and Pamphilus, both of whom relied on enslaved secretaries for their literary projects.[8]

Returning to Dilley’s observations about codex format: Did Eusebius’s canons initially circulate in codex format or as a strictly prefatory paratext? As Dilley suggests, we don’t actually know that either Origen’s Hexapla or Eusebius’s Gospel apparatus was designed for the codex form rather than for the bookroll or for other media formats—such as the loose sheet or the wax tablet. Dilley also suggests that the Eusebian canons may not have always been physically conjoined to a single four-Gospel codex. He suggests that in the era before the single-volume fourfold Gospel became standard, the canons may have circulated separately and perhaps did so in other formats. This is an important set of observations, and I find myself at least mostly in agreement. Eusebius’s Epistle to Carpianus doesn’t specify that the tables will be a bound-in prefatory paratext. And—although the practices of use that I describe in Chapter 1 are oriented around a single Gospel codex—it would actually be more convenient to use Eusebius’s system in multiple volumes and without the need to flip to a prefatory set of tables. These individual volumes would still require Eusebian section and canon numbers. The canons do not work alone.

So far so good. Yet, the widely branching reception of the Eusebian system reflects the circulation of the canons as a bound-in Gospel paratext for a single four-Gospel volume. Dilley observes that our earliest exempla of the Eusebian system appear in relatively expensive deluxe codices; this is true of the earliest physical evidence in Greek, such as the codices Sinaiticus, Ephraemi, and Alexandrinus. But Jerome’s Novum opus, completed in or about 384 CE, indicates that he already envisions a single four-Gospel volume—one in which the Latin Gospels need to be re-ordered into sequence Matthew-Mark-Luke-John in order to correspond with the structure of Eusebius’s project. Extant fifth- and sixth-century codices in Syriac, Latin, Gothic, and Ethiopic likewise indicate the bound-in paratextual location and the single-volume format. Not all Greek examples are from deluxe manuscripts either: The fifth- or sixth-century Epiphanius canons are from a considerably less elaborate manuscript than Sinaiticus or Alexandrinus, but they also reflect a codex format. Finally, in light of the work of Carl Nordenfalk, who reconstructed the probably mise-en-page of the archetype of the text tradition for the canons (transmitted into Latin, Gothic, Armenian, Greek, and other languages), we can be reasonably confident that Eusebius’s project circulated in codex format from a very early stage.[9] This might even have contributed to the growing popularity of this format for Gospel books.

But these counter-observations do not challenge Dilley’s broader point. The canons afford use in a wide range of formats. We know that in some contexts the canons were included in collections of Gospel reference material that didn’t actually have Gospel texts—although the examples that I discuss in the book are from the medieval and early modern periods. It would not surprise me if this had started earlier, in late antiquity. I would love to find more evidence for the range of media formats in which people used Eusebius’s project in late antiquity and I think that by attending to Dilley’s observations here we might be more equipped to recognize that evidence.

As Pragt hints, Eusebius’s segmentation and enumeration of Gospel material is paralleled and expanded by other readers. Attempts to enumerate the numbers of signs, parables, testimonies, chapters, sections, or sayings in different Gospels is widespread. This appears not only in the works of named authors like George of Beʿeltan but also in Syriac manuscript colophons. Moreover, we find it in the Ethiopic Gospel preface Mäqdemä Wängēl, in Greek manuscripts, and in the work of medieval Latin scholars. I’m sure there are more examples. I appreciate Pragt’s invitation to put Eusebius’s project into conversation with other systems of segmentation and enumeration. What is being counted and why? How do readers use these enumerated observations? There is much more to be done here both for the Gospels and for the broader late ancient history of reading.

I describe Eusebius’s project as affording a sort of “distant reading” and suggest that “the pattern-oriented and enumerative modes of analysis that Eusebius introduces into Gospel reading have been part of the methodological equipment of biblical scholarship ever since.”[10] But this isn’t a trajectory that I develop in the book. I think Dilley is right that this aspect of Eusebius’s project might fruitfully be placed in conversation with current work in the digital humanities. I am eager to think more about what that might look like—and what it might help us see. I also wonder if some of these other late ancient enumerative projects might be susceptible to similar fruitful analysis.

Amsler reminds us that the technological innovations of late antiquity are not fundamentally Christian ones—even if subsequent curation of knowledge has preserved a number of creative projects from Christian figures like Eusebius. The sages of rabbinic literature participated in this same set of creative transformations in knowledge in the third and fourth centuries. I can only agree! Dissertations and books often have a chapter that never gets written. In my case, this was an intended chapter on Eusebius’s project in the context of the rabbinic literature of third- and fourth-century Palestine. Bits and pieces of this thinking ended up in various parts of this book, and a few of them have found homes elsewhere, but there’s a great deal more to be done in putting Eusebius—and Caesarean Christian scholarship more broadly—in conversation with the contemporary rabbinic intellectual culture.[11] In this light I’m both grateful for Amsler’s comments today and excited about her forthcoming monograph.

2. Readers

Let’s turn now to readers—both to the many readers of Eusebius’s Gospel apparatus and to the manifold ways that they used his project.

Dilley and Pragt draw attention to one of the striking features of Eusebius’ project: It’s oriented specifically to a Gospel corpus. Eusebius regarded other texts as scriptural—and discusses this in his Ecclesiastical History—but the Gospel apparatus does not map a broader scriptural corpus. No: This is a Gospel project. Even more, it’s about four specific Gospels. Eusebius is explicitly challenging one project of Gospel rewriting (that of Ammonius). I’ve suggested that he’s implicitly challenging another (that of Tatian).[12] He offers a solution to one particular problem of literary pluriformity. Yet precisely because Eusebius’s project is oriented around this specific Gospel corpus, it continues to influence the use of that corpus. To borrow a pair of terms from Hindy Najman, we might describe Eusebius’s project as both retrospective and prospective Gospel writing.[13] It intervenes in a prior (and ongoing) trajectory of Gospel writing and transforms subsequent Gospel reading.

I am struck by Dilley’s proposal that Eusebius’s focus on Gospels parallels Manichaean Gospel reading. The Manichaean teacher Adda brought together multiple Gospel texts against texts from the Jewish Scriptures. I am tempted by this parallel, although in the book I hesitated to draw on the parallels between Adda and Eusebius because it is not clear what Eusebius knew about Manichaean texts.[14] Yet even if direct connections are ephemeral, it is important to note (as Dilley has done) the wide range of readers who were creatively using a pluriform Gospel in late antiquity.

Pragt highlights “some of the ways in which gospel authorship and the parallels and differences between individual gospels were imagined and encountered by Syriac-using Christians in late ancient and early medieval times.” Ishoʿdad of Merv is an interesting case because he’s a figure who I couldn’t demonstrate was using the Eusebian apparatus. I think he probably was. But he doesn’t offer us unambiguous evidence. This is one of the many tricky things about the Eusebian apparatus. Just like many scholars today use, but do not explicitly acknowledge, cross-references, concordances, or Gospel synopses, so also Eusebius’ project was used more often than it was acknowledged.[15] As Knust puts it, “Later writers employed the apparatus in their exegesis, often without giving either Eusebius or his apparatus their due.”

Eusebius’s reconfigured Gospel is only one piece of this puzzle. There is a wide range of paratextual and commentarial interventions through which readers have sought to make sense of their Gospel texts. Ishoʿdad’s description of the circumstances of Gospel writing is an author-oriented biographical approach to the themes of Gospel similarity and difference. We find similar sketches of Gospel writing in commentaries, prefaces, homilies, apostolic acts, hagiographies, and other genres in Greek, Latin, Armenian, Syriac, and other traditions throughout late antiquity and the middle ages. Ishoʿdad is in good company.

It is striking that the profusion of late ancient narratives about Gospel writing are not paralleled by a similar profusion of different projects on the Eusebian model. While Eusebius’s project is radically reconfigured in the Syriac Peshitta—and is also often edited in small ways—it does not spark the same plethora of new projects of Gospel cross-referencing and sectioning. Rather, Eusebius’s project—embedded within Gospel codices—provides the rich tools for other projects of reading in different modes.

Pragt asks about the unguided nature of Eusebius’s project. As she puts it, readers “might … have come across discrepancies or contradictions that would otherwise have gone unnoticed.” This is exactly right. Indeed, as I argue in the book, Eusebius’s project is anything but a “harmony” in the typical sense of the word: “Eusebius’s extensive juxtapositions render Gospel discrepancies more visible to the reader, not less.”[16] This is why scholarly readings of the Eusebian apparatus as an apologetic project fall flat. Eusebius’s project could provide the tools for Augustine’s On the Harmony of the Evangelists or for the critiques of Gospel contradiction advanced by his fourth-century contemporary Porphyry.

In light of this observation, Pragt asks, who is Eusebius’s ideal reader? Eusebius does not answer straightforwardly. His Epistle to Carpianus assumes a reader who wants to “seek” and to “find.” The prefatory letter describes—in some detail—the practical mechanics of using the Eusebian system to find one’s way about among the many “similar things.” But Eusebius presumes the reader’s motivations. This is, perhaps, some of the genius of the project: Whoever Eusebius’ ideal reader might have been, the system itself is vague about what it demands of its reader and of who that reader should be. This opens up the project in a striking way.

Eusebius does not tell us why he invented a system that maps “similar things.” Rather, he tells us that he has made it possible to read these “similar things” and he shows us how to do it. He builds similar things into the Gospel book, into the Gospel text, into the experience of Gospel reading. The similar—or, rather, Eusebius’s idea of the similar—is built into the project at an a priori level. In this, I see Eusebius’s project as part of a much broader set of late ancient epistemological developments, projects that seek to map and coordinate and orient a complex world—to coordinate phenomena human and divine, tangible and numinous, as part of a single intricate cosmos.[17] The significance of similar things seemed obvious to Eusebius—and apparently were likewise obvious and natural concerns for many of his subsequent readers, who put the system to work without problematizing this feature.

3. Imagination

Pragt’s language of the “bibliographical imagination” intertwines with how Knust invites us to consider further “how a claim like “harmony of the Gospels” was used.” She draws attention to the cosmic dimensions of Eusebius’ project. Eusebius uses the language not of “harmony” but of “symphony” (συμφωνία).[18] As Knust points out, this resonates with a broader set of philosophical discourses about cosmic structure and unity—not unlike the συμφωνία that Eusebius discerns (and seeks to produce) in his fourfold Gospel. This is precisely the “second poetic geography” (to quote Michel de Certeau) that I attempt to describe.[19] As Knust observes, the symphonic unity-in-difference of Eusebius’s quadriform gospel is part of what enables it to be “good news” in Eusebius’ fourth-century context. These cosmic and philosophical resonances continue for later readers as well, from Armenia to Ireland and between.[20]

Eusebius does not describe his project as Gospel writing per se. He does not name himself an evangelist. And yet, Eusebius employed emerging textual technologies to create new possibilities of reading, thereby rewriting the fourfold Gospel in a significant and durable way. As many subsequent readers have recognized, Eusebius’s intervention was a watershed in Gospel reading.

From manuscript to manuscript, from printed text to printed text, and now from digital text to digital text as well, rewriting is always a matter of more and less. “When it comes to making texts, it’s rewriting all the way down.”[21] Yet some interventions, some reconfigurations, are more dramatic and influential than others. Eusebius’s intervention is certainly a matter of more. “Eusebius’ intervention in Gospel literature differs to a remarkable degree from the numerous, often minor, differences that occur from manuscript to manuscript.”[22] Eusebius produces not just a different text, but a different kind of text. If the meaning of the text is in its use, then the Eusebian apparatus is striking in the novel modes of use that it affords.

“If Eusebius is an evangelist, then who else is?” Knust argues that modern editors (with their varied textual and paratextual interventions) likewise deploy textual technologies to create new possibilities of reading. I agree. Moreover, these modern rewritings are significant and durable. These texts that we read and study afford particular modes of use. Indeed, I suggest that the textual interventions and paratextual affordances of the modern critical edition (from Karl Lachmann to the Editio Critica Maior) are similar to those of the Eusebian project insofar as the modern critical edition produces not just a different text, but—again—a different kind of text. This text too affords novel modes of use.

I have organized Knust’s probing question under the heading of imagination. Decisions about how to organize our Gospel library, about how to conceptualize texts, editions, and authors—evangelists—are matters of bibliographic imagination. In this we are participating in a project shared with many other readers throughout late antiquity and the Middle Ages. As Knust writes, “writing and reading are always already pre-determined by prior commitments and categories.” I emphasize the inverse as well: We have the opportunity to reimagine our categories and commitments by choosing how and with whom we read.

Histories of biblical texts are often narrated in ways that have a teleology oriented toward Euro-American readers and cultural histories. I have explored ways in which Eusebius anticipates the observations and questions of modern European Gospel scholars. Yet Eusebius’s project is not constrained by this history or these readers. As I explore in Eusebius the Evangelist, the Eusebian apparatus invites and enjoys a much wider range of readers—and a wider range of questions—than modern Euro-American histories of Gospel literature privilege.

This, then, is my answer to Knust’s final question: Why does the Eusebian fourfold Gospel matter today? It matters because Eusebius offers us a tool to think about how we might read Gospels—and other texts—differently. With whom will we choose to read? Whom will we choose to ignore? Which histories of reading matter? Reading over Eusebius’s shoulder affords an opportunity to rethink what we are doing as Gospel readers.

[1] Eusebius of Caesarea, Ep. Carp., lines 32–35 (trans. Eusebius the Evangelist, xv).

[2] Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. Steven F. Rendall (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 105.

[3] Eusebius the Evangelist began as a dissertation at the University of Notre Dame, supervised by the incomparable Blake Leyerle and David Lincicum. I will forever be grateful for their guidance, kindness, and critique. Many others provided feedback on arguments, facilitated access to relevant manuscripts, shared unpublished work, and offered encouragement. For this, too, I am deeply grateful. My work on the Eusebian apparatus has developed in productive conversation with the recent work several other scholars, especially Matthew Crawford, Martin Wallraff, and Francis Watson. See in particular Matthew R. Crawford, The Eusebian Canon Tables: Ordering Textual Knowledge in Late Antiquity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019); Martin Wallraff and Patrick Andrist, eds. Die Kanontafeln des Euseb: Kritische Edition, Kommentar und Einleitung (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2021); Francis Watson, The Fourfold Gospel: A Theological Reading of the New Testament Portraits of Jesus (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2016).

[4] de Certeau, Practice, 105.

[5] My approach contrasts with Grafton and Williams’ influential monograph: Anthony Grafton and Megan Hale Williams, Christianity and the Transformation of the Book: Origen, Eusebius, and the Library of Caesarea (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006).

[6] Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations (Oxford: Blackwell, 1952), §43; cf. Eusebius the Evangelist, 4–8.

[7] Michael Polanyi, Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958); Thomas Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962).

[8] I note my intellectual debts to Candida Moss, whose work on enslavement and early Christian literature has deeply shaped my own thinking; see in particular, Candida R. Moss, “Fashioning Mark: Early Christian Discussions about the Scribe and Status of the Second Gospel,” NTS 67 (2021): 181–204; “Between the Lines: Looking for the Contributions of Enslaved Literate Laborers in a Second-Century Text (P. Berol. 11632),” Studies in Late Antiquity 5 (2021): 432–52; “The Secretary: Enslaved Workers, Stenography, and the Production of Early Christian Literature,” JTS (forthcoming).

[9] Carl Nordenfalk, Die spätantiken Kanontafeln: Kunstgeschichtliche Studien über die eusebianische Evangelien-Konkordanz in den vier ersten Jahrhunderten ihrer Geschichte, 2 vols. (Goteborg: Isacson, 1938).

[10] Eusebius the Evangelist, 30.

[11] Jeremiah Coogan, “Tabular Thinking in Late Ancient Palestine: Instrumentality, Work, and the Construction of Knowledge,” in Knowledge Construction in Late Antiquity, ed. Monika Amsler (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2023), 57–81.

[12] See discussion of Tatian, Ammonius, and Eusebius in Eusebius the Evangelist, ch. 3.

[13] My thinking is influenced by Hindy Najman, “The Vitality of Scripture Within and Beyond the ‘Canon’: Transformations in Second Temple Judaism,” JSJ 43 (2012): 497–518.

[14] One worrying quibble: When Epiphanius (Pan. 66.21) refers to Eusebius’ treatment of the Manichaeans, does he have a freestanding work in mind or is he simply referring to the briefer discussion in Hist. eccl. 7.31?

[15] On the ephemerality of tracing the use of reference tools and scholarly apparatus, see especially Eusebius the Evangelist, ch. 5.

[16] Eusebius the Evangelist, 116.

[17] Here I have learned especially from the work of Mike Chin and of Blossom Stefaniw, especially C. M. Chin, “Cosmos,” in Late Ancient Knowing: Explorations in Intellectual History, ed. C. M. Chin and Moulie Vidas (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2015), 99–116; Blossom Stefaniw, Christian Reading: Language, Ethics, and the Order of Things (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2019).

[18] My thinking about συμφωνία has benefited especially from Sébastien Morlet, Symphonia: La concorde des textes et des doctrines dans la littérature grecque jusqu’à Origène (Paris: Les belles lettres, 2019); see discussion in Eusebius the Evangelist, ch. 4.

[19] de Certeau, Practice, 105.

[20] This is something that I have continued to explore in my ongoing research, especially Jeremiah Coogan, “Reading (in) a Quadriform Cosmos: Gospel Books and the Early Christian Bibliographic Imagination,” JECS 31, no. 1 (forthcoming 2023).

[21] Eusebius the Evangelist, 92.

[22] Eusebius the Evangelist, 92.

Jeremiah Coogan is Assistant Professor of New Testament at the Jesuit School of Theology of Santa Clara University (Berkeley, California). He is a historian of early Judaism and early Christianity whose research focuses on reading practices, material texts, and the social history of the Roman Mediterranean. His new monograph, Eusebius the Evangelist (Oxford 2023), analyses Eusebius of Caesarea’s fourth-century reconfiguration of the New Testament Gospels as a window into broader questions of technology and textuality in early Christianity and the late ancient Mediterranean.