I’d like to begin by congratulating Professor Coogan for writing a remarkable book. Eusebius the Evangelist has much to recommend it as a work of basic research. It builds on current scholarship related to the Eusebian Canons, including much recent work of quality, while bringing a fresh perspective based on a sophisticated approach to the material text. The book also offers us a heightened sense of the historical antecedents for Eusebius’s project, on the one hand, and its later reception, on the other. Indeed, Eusebius the Evangelist is perhaps most remarkable for how it ties together earlier forms of what Coogan denotes as Gospel writing—both the canonical Gospels and so-called apocrypha as well as harmonies—with the Eusebian Canons and their attendant reading practices; and also with the reception of the canons in subsequent centuries and across multiple cultures. Somewhat ironically, the most opaque part of the study—and this is due to the nature of the evidence rather than the argument of the book—remains the work of Eusebius himself in crafting the Canons. While we are comparatively well informed about the career of the scholar and bishop, and even have his Epistle to Carpianus explaining the rationale for the Canons, we know little about why he took the project up, beyond the largely intellectual and practical reasons he states in that same Epistle; nor can we be confident about his methodology in collecting, storing, writing, and revising the relevant data; nor do we know how the earliest Eusebian Canons appeared and what they looked like, because the earliest extant manuscripts are from the fifth century CE. Similarly, we will need a full reassessment of date ranges for early Christian manuscripts, as well as a clear accounting of their paratextual and other codicological features, to better contextualize the emerging textual practices during Eusebius’s own time.[1] My subsequent comments, organized as five initial reflections, were prompted by Coogan’s many strong insights, and in response to the ongoing holes and ambiguities in our source material.

First Thought: The Biblical Antitheses of Adda, Disciple of Mani

Professor Coogan has done an extraordinary job in exploring the various antecedents for Eusebius’s work of rewriting/repositioning the Gospels, including Marcion’s Antitheses. There is one important predecessor/dialogue partner that he and (to my knowledge) his predecessors have overlooked, one which is based on Marcion’s work, but which almost certainly presented a more pressing concern to Eusebius as an intellectual and bishop in the late third- and fourth-century Eastern Mediterranean: the polemical work of Adda, a prominent disciple of Mani and missionary to the Roman Empire, active in Syria and Alexandria, Egypt from the middle of the third century. We know that Mani and his followers were a major concern for Eusebius, who treats them in the Ecclesiastical History 7:31. He also may have written a lost treatise Against the Manichaeans (cf. Epiphanius, Panarion LXVI.21), which would have been among the first, or perhaps even the very first, Christian examples of this widespread heresiological sub-genre. Adda’s critique of the Jewish Bible through the juxtaposition of passages from it with seemingly contradictory passages from the New Testament seems to have been a mainstay of the Manichaean mission for several centuries. It can be partially reconstructed through the works of Augustine, especially the polemical treatise Contra Adimantium, as well as a section of the Acta Archelai which Jason BeDuhn shows was likely also from the same work.[2] Some of the passages discussed by Adda are Gospel passages, and sometimes several Gospel passages together are juxtaposed with a corresponding passage from the Jewish bible. It is difficult to determine how systematic Adda’s technique of reading the Gospels together was, nor do his parallel passages, at least those which can be reconstructed, correspond exactly to Eusebius’s Canons. But the Manichaean Gospel re-configurations in Adda’s work represent an alternative practice of Gospel reading for Mediterranean Christians, and once again highlight strong continuities between communities that have been retrospectively dichotomized as heretical and orthodox. It also highlights Eusebius’s decision not to include anything else beyond the Gospels in his Canons, that is, no Jewish Bible, nor the other books of the New Testament, however that might have been defined.

Second Thought: Planning and the Placement of Paratext

Professor Coogan effectively links the Eusebian Canons to various paratextual devices of the imperial and Late Antique periods, across a range of literatures. Let’s take a closer look at one of these, the table of contents. Table of contents often occur at the beginning of a work, but there are exceptions. As an example, the Psalms manuscript, from the Medinet Madi Library of Manichaean Codices, among the very largest surviving papyrus codices, has an ordered list of the Psalms by group, with incipts, at the back of the codex.[3] This has been called an index in scholarship, but it is really a table of contents. Why put the table of contents at the back? Perhaps for codices in which the specific contents were gradually chosen (for example, whichever Manichaean Psalms were easily accessible at the moment), as opposed to precisely planned at the outset (for example, a four-Gospel codex). This placement might suggest that the Eusebian Canons were put at the front in the case of “pre-ordered” or planned codices, presumably including four-Gospel codices. But they may have been used in other contexts as well.

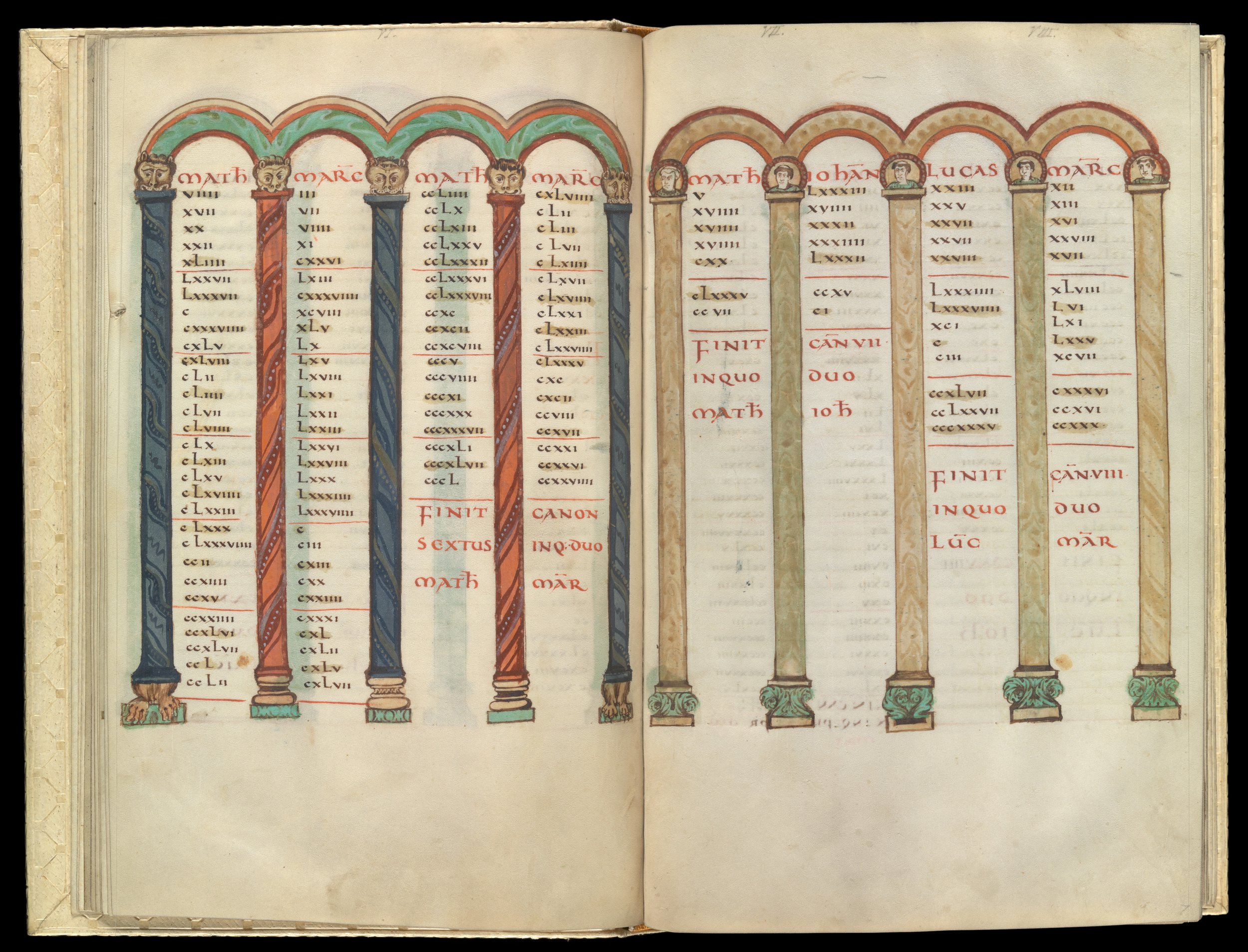

Third Thought: The Eusebian Canons beyond the Codex: Early Textual Media

We should not assume that the Canon tables were originally developed to hold the “introductory” position in which they find themselves in the extant manuscripts. Indeed, the data obtained by Eusebius himself for the Canons may have been collected using a notebook, perhaps a waxed, wooden, tablet, and taken its initial shape in that format as well. It is also quite likely that the early Eusebian canons were copied and circulated as single-leaves in Antiquity, which would have facilitated study across multiple codices, especially in the era before four-gospel codices became the norm. The early canon tables with which we are familiar come exclusively from high-cost, if not luxury manuscripts, and this is why they have been preserved, at the expense of my hypothesized single-leaf sheets which would have been portable from manuscript to manuscript.

Fourth Thought: Affordances for the Comparative Study of the Global Book

Professor Coogan’s uses Caroline Levine’s concept of “affordances,” that is, “the potential uses or actions latent in material and designs,” as a general framework through which to discuss the role of the Eusebian canons as an integral aspect of the material book.[4] I very much appreciate this perspective, and it suggested an additional question to me: did the Canons “fit” the codex format better than the scroll format? It is important to note that we have no evidence that either Eusebius’s Canon or Origen’s Hexapla were originally written for the codex. A scroll format would have been equally suited for such a visualization at the beginning of the work. The concept of affordances also allows an even broader perspective, with a nod now to my participation with Professor Coogan in the Mellon Society of Fellows in Critical Bibliography, where we often have conversations with colleagues in book history from different disciplines and specializations. To my knowledge, Coogan’s use of “affordances” to understand material textualities may be new in global book studies more broadly. Indeed, it could easily be applied to various aspects of book technology, at different scales. Take connections between book materials and book formats and their gradual development over centuries. Leather or parchment, for example, was first developed as a scroll format, but was apparently less used in the Mediterranean than papyrus; on the other hand, as the use of the codex steadily increased, parchment was more frequently employed in its production, perhaps because it responded better to folding than papyrus.

Fifth Thought: Distant Reading from the Codex to Digital Media

Professor Coogan’s work on the reception of the Canons, which he characterizes in an aside as a form of non-computational distant reading (p. 30), has given me another interesting framework for my ongoing work on Digital Humanities and biblical studies, including the potential for computational distant reading.[5] For example, topic modeling, an unsupervised algorithm for identifying topics within a given corpus, with its attendant segmentations of the texts in that corpus, is in some sense related to the suppositions of the Eusebian canons, though it is based on digitized data in spreadsheets and their attendant visualizations. Coogan’s various categories for traces of reading, such as juxtaposition, efficiency and access, and remapping may very well have compelling analogues in the realms of digital distant reading.

Conclusion

I hope that these virtual marginal notes on Coogan’s impressive book have drawn attention to the different ways in which it breaks new ground. First as a widening of the concept of Gospel reading that takes us back to the first Gospel compositions, through the pre-Constantinian period, until we see the work of Eusebius in this wider context, breaking down notions of orthodoxy and heresy. While not based on a close study of a select group of manuscripts, Eusebius the Evangelist often centers the materiality of the text in its analysis, and encourages the reader to experiment with the Canons—easier said than done, of course, if one doesn’t have an ancient manuscript in one’s hands, but it’s possible to do makeshift experiments nonetheless. This can include thought experiments, to help us imagine textual practices relating to the Canons during periods for which we do not have evidence. Finally, Coogan opens new interpretive possibilities with the evidence that we do have, that is, the later manuscripts, by tracing a reception history of the Canons in multiple linguistic and cultural contexts. It is rare to have a book tie together the Gospels across so many periods, and it does so not by examining the development of particular stories, but by compositional and reading practices.

[1] Cf. Brent Nongbri’s Early History of the Codex project.

[2] I follow the reconstruction in Jason BeDuhn, “Biblical Antitheses, Adda, and the Acts of Archelaus,” in Jason BeDuhn and Paul Mirecki, eds., Frontiers of Faith: The Christian Encounter with Manichaeism in the Acts of Archelaus, NHMS 61 (Leiden: Brill, 2007), 131-147.

[3] C.R.C. Allberry, A Manichaean Psalm-book. Part II (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 1938), XXII.

[4] Caroline Levine, Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), 6.

[5] Paul Dilley, “Digital Philology between Alexandria and Babel,” in Claire Clivaz, Paul Dilley, David Hamidovic, eds., Ancient Worlds in Digital Culture (Leiden: Brill, 2016), 17-34.

Paul Dilley is Associate Professor of Ancient Mediterranean Religions in the departments of Classics and Religious Studies, as well as the Center for the Book, at the University of Iowa. He specializes in the Religions of Late Antiquity, especially early Christianity, with an approach that integrates book studies, digital humanities, philology and anthropology/cultural history. He is the author of Monasteries and the Care of Souls in Late Antique Christianity: Cognition and Discipline (2017, Romanian translation 2021), numerous edited volumes, articles, and chapters, and is a co-editor of several works from the Medinet Madi Library of Coptic Manichean codices. Dilley has been a fellow of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation and the American Research Center in Egypt, among others; a member of the Institute for Advanced Study; and is a senior fellow of the Mellon Society of Fellows in Critical Bibliography.