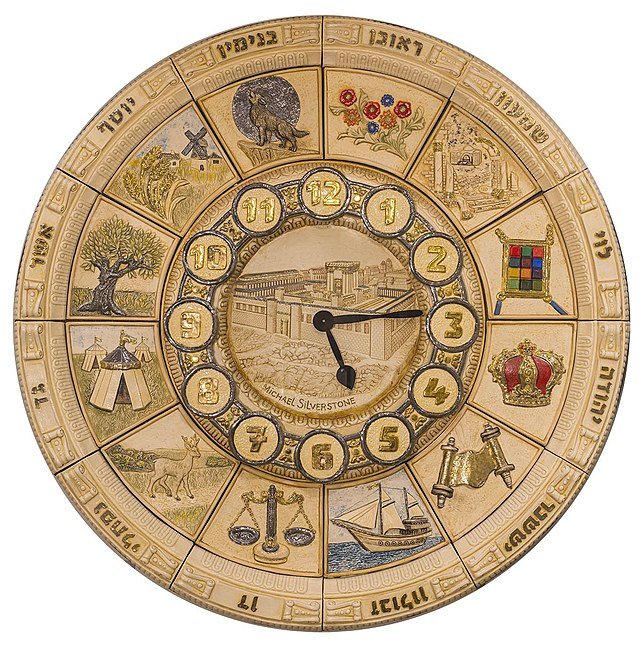

A sculpted ceramic clock, by Michael Silverstone, depicting emblems of the twelve tribes of Israel surrounding a reconstruction of the Temple. Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons.

The story of the groups that I will call, in this essay, “Hebrew Israelites” – who have also been called Black Israelites, and who are African-American religious communities that identify as Israelites, or Jews – is not really mine to tell. Nor, for that matter, is it an easy one to tell in brief. There’s a great book about it, Jacob S. Dorman’s Chosen People: The Rise of American Black Israelite Religions. I learned a lot, while writing this piece, from Yvonne Patricia Chireau’s essay “Black Culture and Black Zion: African American Religious Encounters with Judaism, 1790-1930, An Overview” and a recent piece by Andre E. Key, Walter Isaac, and Tamar Manasseh, offering an insider account of one group’s experience and understandings. I heartily recommend all of these for readers who want to know more.

My approach to the topic is, however, shaped by two experiences that offer me a way in. First, that I have recently written a book that traces the history of peoples all around the world who have identified as Israelites from biblical times to the present. I did not include the Hebrew Israelites here, but I did discuss certain American groups that identify as Israelites, including the Mormons, and other groups, like the Beta Israel whose histories are relevant here.

Second, that I am myself Jewish, with a Jewish family, in an America where antisemitism and antisemitic violence is sharply rising. Some of these groups are antisemitic, many are not. More specifically, the umbrella term “Hebrew Israelites” certainly includes groups who are not antisemitic – and some who want only to be considered Jewish like any other Jew. That in itself is an important point to make, and one I will discuss below. The antisemitic ideas expressed in recent controversies surrounding figures such as Kanye West and Kyrie Irving, however, are also poorly known and poorly understood. So, I consider it both useful and important to offer this little primer.

You may not know it, but you live in a world full of Israels. If there aren’t groups claiming descent from the ancient Israelites on every continent, it is only for this reason – that Antarctica isn’t trying hard enough. And strange as it may seem at first blush, it really makes a lot of sense. After all, the Hebrew Bible has long since ceased being the traditions of one ancient people in one ancient place long ago. But, it still tells the story of one ancient people, in an ancient time and place. Its poetry is still the poetry of one ancient people; its prophecy still describes what did, would, and sometimes will happen to one ancient people. What could be less surprising, then, that audiences will identify with the ancient people who are the protagonists of their scripture on a figurative level– this is like the exodus, this is like David and Goliath. And of course, too, the figurative has sometimes bled into the literal. And so, generation after generation, there have been those who imagine that maybe god’s chosen people, god’s sacred possession, the subject and object of biblical prophecy, are really here and now.

It should hardly be surprising either, then, that the idea of Israel in America actually long pre-dates Hebrew Israelitism. Indeed, I would say that the latter has as many as four different roots in American soil, though Dorman is quite right to prefer a different metaphor – that of the rhizome, which comes to us from the work of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. Its major drawback, of course, is that you always have to explain what a rhizome is, when you want to use it as a metaphor. But that’s not so hard to do - it’s a root system that is “not linear but lateral, nonhierarchical, and multiple” (Dorman 6). More simply, we could think of the difference between the sink and the ocean. We are not simply influenced by what we go deliberately to drink, which came to us through a pipeline from a plant. We swim in a vast sea of influences, which shape us in ways we may not even notice. We can take them in without thinking about it.

First, then, and even before the European colonization of America, there was a European habit of using the Hebrew Bible as an anthropological source book. Again, it makes sense. If you literally believed in the biblical flood, you would also believe that everyone on Earth was a descendant of Noah. Thus, Genesis 10, the so-called “table of nations” – which describes the descent of various nations from Shem, Ham, and Japheth, Noah’s three sons – became a kind of guide to who might be out there. In practice, it was not that simple. European perceptions of the wider world were also shaped by other texts like The Alexander Romance and “The Letter of Prester John,” which offered extraordinary accounts of peoples Alexander the Great had conquered and encountered, and tales of a great Priest King to the east. And they were shaped by 2 Kings 17, the biblical account of the conquest of Israel – and not Judah – by the Assyrian empire, with the loss of Israel’s tribes into an exile from which they never returned.

This was the genesis of the legend of “ten lost tribes of Israel,” but they could all work together, depending on what made sense at the time. The Mongols, during the invasions of the 13th century could, from the perspective of Christian Europe, be the armies of Prester John, hastening to help in the Crusades when they defeated Muslim armies in the east. When they got closer to Europe, they could be, instead, the Lost Tribes of Israel, come for revenge, or else, some of the barbarian hordes Alexander the Great was supposed to have locked up in the Caucasus mountains. Or they could be other biblical peoples associated with the end times – Gog and Magog, for example. And this tendency to identify the other in biblical terms was certainly not limited to Christian intellectuals alone. The famous Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela, who was a Jew from Spain who traveled extensively and composed this report found both real and imagined Jewish communities all over the east. He marveled at how much better the situation of the real communities seemed to be than those of medieval Europe, and consistently imagined the descendants of the Lost Tribes living in greater freedom and prosperity still.

Ultimately the first root – rhizomatically, one might say – produced the second, what is usually called the “Jewish Indian Theory.” Elizabeth Fenton, in her recent study, has suggested that the “Hebraic Indian theory” is a better term (Old Canaan in a New World, 3-4) for reasons that are also important when we talk about early African American claims to a Jewish identity. The idea that the native Americans might be the lost tribes of Israel – which emerged already in the early 16th century – came from people who knew little of the Jews of their day and who used “Jew” and “Israelite” interchangeably. Thus, Fenton’s is a more accurate description. They believed the Native Americans, or some of the Native Americans, might be Israelites, rather than Jews, but they did not know the distinction between the same terms. Still, the idea was popular. William Penn once said that “there were so many Jews around it was like being in a Jewish quarter in London.” Dr. Benjamin Rush asked Lewis and Clark to keep an eye out for Israelites. Elias Boudinot, one-time member of the Continental Congress and director of the U.S. Mint, wrote a book called A Star in the West: A Humble Attempt to Discover the Long Lost Ten Tribes of Israel, Preparatory to Their Return to Their Beloved City Jerusalem – of course, in America.

Third, the history of looking not just outward but inward for Israelites is long, too, but where America is concerned, an important fact is that a number of British Protestant intellectuals in the mid-17th century began to blur the lines described above, between figurative and literal identifications with Israel. Figuratively, they were convinced that Britain itself was a chosen nation and God’s chosen people, and they were armed with reasonable intellectual arguments – that, for example, New Testament texts like Romans (11:25), “referred to the whole New Testament Church of Gentile and Jew” (Toon, Puritans, 126). This is a verse that says that “the fullness of the nations” will go into Israel and it was followed by verses describing how “all Israel” will be saved. But, the idea that Anglo Protestants were really the new Israel, and even, perhaps the old Israel is visible in places like a speech John Durie gave before the House of Commons, entitled “Israel’s call to march out of Babylon into Jerusalem,” equating the Protestant Reformation with the return from Babylon (Tobolowsky 2022: 155).

It was Durie who, along with Thomas Thorowgood, helped inspire the famous work of the (Jewish) Menasseh ben Israel, Hope of Israel, which purported to show that the lost tribes of Israel were indeed to be found all over the world, including America. Meanwhile, we might think of the Mormon religion – a homegrown American one – as a synthesis of sorts of these last two roots. Mormonism arose in the 1820s and ‘30s largely among the descendants of British Protestants living in America. The Book of Mormon offers an account, supposedly first hand, of an Israelite tribe coming to America, fighting each other, and, in a sense, disappearing into the native community. But it wasn’t long before Mormon thought encompassed the idea that they themselves might be Israelites – or even that being of Israelite descent, anywhere in the world, via the dispersion of the Lost Tribes of Israel, might predispose someone to be open to the Mormon message. Still today, Mormon missions are often conceptualized as a search for Israelites, and the important Mormon coming of age ritual, the patriarchal blessing – developed to echo the Blessing of Jacob in Genesis 49 – imparts to many Mormons knowledge of which tribe they descend from.

Finally, long before literal identifications with Israel or with the Jews appeared in African-American communities, there was a vibrant tradition of figurative identifications with Old Testament figures and events, especially among enslaved Black Americans. The reasons are obvious enough. As Chireau puts it

The slaves believe themselves to be another Israel, a people who toiled in the ‘Egypt’ of North America but who were providentially guided by the same God who had led the Jews into the Promised Land. Projecting their own lives onto Old Testament accounts, African Americans recast their destiny in terms of the consummation of a divine drama, the event of the Exodus (18).

She notes as well the prominence of Old Testament figures in spirituals – “Wrestling Jacob,” “Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel,” “Go Down, Moses” and so on. Thus, Hebrew Israeliteism grew out of rich soil, well-prepared for its emergence.

To be clear, there have always been Jews who would today be regarded as people of color. Judaism is a religion, not a race. The idea that Jews are inevitably white is a product of the prominence of Ashkenazi Jews, which is to say, central and eastern European Jews, in cultural representations. There are Sephardi Jews and Mizrahi Jews who tend to be darker skinned, and there are groups like the Beta Israel of Ethiopia that I will discuss below. There are African-American converts to Judaism, and the descendants of converts. There is, as well, a long American history of mutual influence between Black and Jewish communities, stemming from a tendency to identify with each other as the victims of discrimination at the hands of white Christians. Deanne Shapiro discusses the influence of this vision on the thought of Booker T. Washington, among others. Eventually, the idea of a true homeland that was somewhere else could come to serve as a shared touchstone.

When I am talking about Hebrew Israelites, however, I am talking about groups that at least originated out of a particular movement that was what scholars would call “syncretic” – which is to say that it combined beliefs and practices that were regarded, rightly or wrongly, as “Israelite” or “Jewish” with elements that are recognizably Christian or sui generis. Today, and for some time, some of these groups understand themselves to be simply Jewish, while others remain sui generis, members of churches with their own names and practices that are quite outside the orbit of normative Judaism – typically without interest in coming inside. They have a range of beliefs about their relationship to Israel, Israelites, and Jews, some of which are harmful, some not. The number of groups and the diversity of their beliefs is of course what makes Hebrew Israeliteism such a complicated topic to discuss – while the question of what counts as an antisemitic belief, or a Jewish one, requires considerable sensitivity in the attempt.

Still, there are a few things we can say about the origins and development of Hebrew Israeliteism, in broad strokes, which might prove useful. First, it developed in essentially two phases. The first took place before the end of the 19th century. A central figure here is William Saunders Crowdy, a Black Union Army veteran born into slavery, who was living in Oklahoma in the early 1890s when he started having visions that Black people were the descendants of the lost tribes of Israel. Again, aspects of this idea might be older, but there is no evidence to suggest “that enslaved Africans brought an identification with the ancient Israelites with them” (8). There is evidence to suggest that Crowdy was swimming in the sea already described – that he was influenced, to some extent, by the Anglo-Israelite ideas discussed above, and “Masonic-Israelite” ideas, in his capacity as a Freemason (7-8).

At any rate, Crowdy would create the Church of God and Saints of Christ, and travel the country with his message. He also sent proselytizers all over the world – not without effect (Tudor Parfitt, Black Jews in Africa and the Americas, 90). The Church still exists today, headquartered in Suffolk, VA, and its self-representation is a case in point. On its website, it notes the church’s adherence “to the tenets of Judaism,” and its celebration of numerous Jewish holidays, alongside its “promulgation of that faith in the teaching of the prophet Jesus.” This it calls “‘Prophetic Judaism’ since it came down to us by divine revelation and because of its continuing reliance upon the medium of prophecy… as the vehicle for God’s revelation.”

Another early figure, harder to pin down, is Frank S. Cherry, who would establish the “Church of the Living God, the Pillar and Ground of Truth for All Nations.” Typically, he is described as having founded his church in Chattanooga, Tennessee around 1886, but as Chireau notes, this is actually hard to prove (Chireau, 30, notes 12-13). It is clearer that it was established – or re-established – in Philadelphia in 1912. Cherry is, to some extent, the spiritual forefather of the strand of Hebrew Israeliteism that is antisemitic, and for that matter, anti-white. Unlike Crowdy, he taught that the Black people were the real Jews and that a great deception was practiced to keep them from that truth (Parfitt, 89). He also preached a coming race war in which Jesus would return to destroy the white race. Today, various groups that the Southern Poverty Law Center refers to as “Radical Hebrew Israelites” – and designates as a hate group – espouse similar ideas.

The second phase of Hebrew Israelitism began roughly in the 1910s, the era of the Great Migration – the mass movement of Black people away from the Jim Crow South into the west and into the industrial centers of the Midwest. Earlier groups may have identified as Jewish – or not. Usually, however, like the proponents of the Hebraic Indian Theory, whichever they did was done without much familiarity with mainstream Judaism as it is actually practiced – though Chireau suggests that recent immigrants from South America and the West Indies might also have brought their own influences, given the long history of Judaism in these regions (22). At any rate, this migration brought many Black southerners into contact with established Jewish communities for the first time, and often in ways that brought them closely together – living in the same neighborhoods, and so on. The result was a number of new movements that more heavily judaized, borrowing more from mainstream and contemporaryewish practices and beliefs. Key figures here include Arnold Joseph Ford and Wentworth Arthur Matthew, both of whom went by the title “Rabbi” and opened congregations in Harlem in the 1910s and ‘20s.

Ford, who knew Hebrew and was involved in Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association, founded Beth B’nai Israel in 1923 and, with Mordecai Herman, the Moorish Zionist Temple at around the same time, then, finally, Beth B’nai Abraham (Dorman 119-120). Dorman suggests that Ford’s “preference for the terms ‘Hebrew’ and ‘Israelite’ rather than ‘Jew’ helped to carve out an autonomous identity separate from white Jews” (123). But “Ford’s Hebrew, for their part, were sincere in their desire to practice Judaism” (124). They worshipped with a Torah, offered Hebrew classes, and offered a vision, like Crowdy and Cherry, of descent “from the original Jews” (125-128). At one point, Ford claimed that the original Israelites had come from Nigeria before they came to Palestine, as well as tracing their history back to ancient Carthage (129). Eventually, he emigrated to Ethiopia, in an attempt to found a colony, but died in 1935 before it got off the ground.

As for Matthew, who would found the Commandment Keepers Congregation in 1919, this was an even more heavily Judaized group. Dorman describes it this way:

From the 1930s to the 1970s, a visitor to the Ethiopian Hebrew Commandment Keepers congregation in Harlem on a Saturday morning would have found Rabbi Matthew leading a room of African Americans engaged in Hebrew prayer, the men wearing Jewish prayer shawls and skull caps, the women sitting in a separate section at the rear. At the midpoint of the service, the diminutive, bearded rabbi would remove the Torah from its enclosure and lead others around the synagogue (152).

They, too preferred “Hebrew” and “Israelite” instead of “Jew” (152), but it is typical of the second phase that the Commandment Keepers “progressively incorporated more Jewish rituals and decreased the prominence of Jesus as the decades passed” (153). Matthew, who also ordained rabbis, taught that Black people were descended from Abraham, but did not teach, as Cherry and others had, that Jewish people had conspired to cover this up (Chireau 24).

Both Ford and Matthew, and others of their day, were also strongly influenced by what is usually called “Ethiopianism,” which began in Africa, and was named, in part, from Psalm 68:31: “Let Ethiopia stretch out its hands to god.” In America, Ethiopianism, as Deanne Shapiro puts it in her study of “Factors in the Development of Black Judaism,” was a kind of African “Zionism” (261), or nationalism, which inspired groups like the Nation of Islam. In America, Hebrew Israelites were inspired by the Ethiopian defeat of Italy in the 1890s, and by a growing global awareness of Ethiopian traditions – which, as I will discuss, were not just the Beta Israel’s, but common among Ethiopian Christians as well – of descent from Solomon and Sheba. Dorman notes that “Ethiopianist preachers led to a second wave of Black Israelite churches… in northern cities like Detroit, Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia” (9-10). Certainly, Ford’s immigration to Ethiopia reflects his commitment to these ideas, while Matthew “who died as ‘Chief Rabbi of the Ethiopian Hebrews of the Western World’” (154) taught that African-American Jews were descended from these Ethiopians (Chireau, 25).

At any rate, throughout the twentieth century, a number of different Hebrew Israelite groups would be formed, offering diverse accounts of their Israelite and Jewish heritages, diverse constellations of Jewish practices, and diverse levels of commitment to the idea of being Jews like any other Jews. Some, like Ford and Matthew’s congregations, began to identify more and more as Jews and to take typical Jewish observances more and more seriously. Others redoubled their commitment to ideas like Cherry’s – of a Jewish conspiracy, or a Jewish and white conspiracy, to steal and obscure the true Jewish or Israelite heritage of the Black people.

One crucial recognition, where the study of religion and culture are concerned, is that religions do not merely swim in oceans. They are part of oceans. They contribute to them. The Southern Poverty Law Center’s website on Radical Hebrew Israelites offers an illustrative case in point. They mention the fact that Nick Cannon, on his podcast “Cannon’s Class,” stated overtly that “they (Jews) have taken our birthright.” As the author of the post observes, “[n]either Cannon or [his guest, Professor Griff] are known to be members of any RHI [Radical Hebrew Israelite] group.” I also cannot tell you if Kanye West or Kyrie Irving are members of RHI groups, or merely influenced by ideas that arose within them. Cannon went on to say “You can’t be antisemitic when we are the Semitic people. When we are the same people who you, who they want to be, that’s our birthright.” West, it turns out, said the same thing: “I actually can’t be Anti Semitic because black people are actually Jew [sic] also.” So did Kyrie Irving: “I cannot be antisemitic if I know where I come from.”

When we view these last assertions in the context of the history just described, they are a bit silly – a Jew can spread antisemitic stereotypes as easily as anyone else – but not anti-Semitic in and of themselves. What is antisemitic is the other part. When West said that Planned Parenthood was created “with the KKK to control the Jew population. When I say Jew, I mean the 12 lost tribes of Judah, the blood of Christ, who people known as the race Black really are” that is antisemitic. When Irving helped popularize the documentary, “Hebrews to Negroes” – a 2018 film based on a book that he helped make a bestseller on Amazon which espouses the idea that Black people are Jews instead of the Jews – this was antisemitic, and dangerous.

And when I say dangerous, I want to be clear that I mean actually dangerous. Too often, this is a conversation framed around hurt feelings. I can’t speak for everyone, but as a Jew who grew up in the South, the existence of antisemitism, and the casual experience of it, are things I learned to live with, and still do . But when someone repeats any version of the idea that the Jewish people are behind a massive conspiracy to control reality, it motivates people to attack Jews. I grew up in Dallas. I’m a Dallas Mavericks fan. Kyrie Irving moving to town means that someone who helped sell a lot of copies of a book that claims that my people and my family are part of a vast, millennia-long conspiracy to steal what rightfully belongs to the Black people, and to keep them down, means that Kyrie Irving, specifically, has directed violence at my people and my family. And in the likely event that neither he, nor Kanye West, nor Nick Cannon are committed members of particular Radical Hebrew Israelite groups, we see the danger of the ideas these groups spread, well beyond their membership. They also amplify ideas found elsewhere. The Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh was attacked by a white man, but he believed that Jews were satanic, and that they were conspiring to bring immigrants into the country to kill white people. There is no decent, safe, respectable way to believe in Jewish conspiracies.

At the same time, there are plenty of Hebrew Israelite groups that do not embrace anti-semitic conspiracy theories, and do not teach that the Black people are the real Jews instead of the Jews. Neither is religious syncretism a crime or, in my view, a moral failing. In the grand sweep of religious history, the formation of religious movements that borrow from other religious movements is entirely normal and unexceptional. And this is an important point. Broadly speaking, the existence of Radical Hebrew Israelite groups has been troubling to Jewish groups for obvious reasons. But, the existence of any Hebrew Israelite groups at all has also been troubling to some because of the challenge to traditional ways of thinking about who the Jewish people are and where they come from that Hebrew Israelites represent. And that is a more complicated problem.

My intention in this final section is not to tell anyone how to feel about issues of Jewish heritage and belonging, on either side of the fence. I can only speak for myself. But when I think about the Hebrew Israelites, I tend to think of the Beta Israel of Ethiopia. The Beta Israel, so far as I know, are still the only group from outside of Israel to receive official recognition by Israel’s court system on the basis of their descent from a lost tribe of Israel – in this case, the tribe of Dan. I do not think they are really descended from the tribe of Dan. But the thing is, the evidence most strongly suggests that they did not think of themselves as descendants of the tribe of Dan either – until they began to encounter emissaries from the normative Jewish world beginning in the late 19th century. In fact, it may not be the most common Beta Israel tradition of origin even today.

Instead, in Ethiopia, there is an indigenous tradition called the Kebra Nagast, sometimes called Ethiopia’s “national epic.” In any case, it is the founding tradition of the Solomonic dynasty, which ruled Ethiopia from the late 13th century until the deposition of Haile Selassie in 1974. It tells the story, among others, of one Menelik, the son of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. Menelik grew up in his native land – Ethiopia – but visited his father when he came of age and returned with two things – the ark of the covenant, and an honor guard of Israelites (KN 32, 39, 48). The Solomonic dynasty was Christian – the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church dates back to the fourth century CE – and so we see that in Ethiopia, identifying as Israelites was common among Christians too. In fact, Steven Kaplan suggests that references to Israelites in Ethiopian sources are more likely to point to members “of the imperial [Christian] dynasty… [rather] than to an ‘Ethiopian Jew’” for much of Ethiopia’s history (Kaplan, The Beta Israel, 10). We have already seen the influence of these traditions on American “Ethiopianist” communities.

We cannot know the whole history of the Beta Israel with any certainty – scholars still debate, for example, whether or not the community descends from an early Jewish settlement in the area. On the one hand, there were early Jewish communities in the wider region – the kingdom of Himyar, just across the Red Sea, embraced Judaism sometime in the fourth century, for example. On the other hand, there is no real evidence of Jews in Aksum, the precursor kingdom of Ethiopia, itself. Anyway, for me, this is the crucial point: both Ethiopian records and Beta Israel tradition actually converge on the conclusion that the Beta Israel community began to take familiar form only in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries CE. The community was shaped by its opposition to, and conflict with the Ethiopian Christian majority and the Solomonic kings, and it’s likely that from the beginning their traditions reflected as much. When James Bruce, the Laird of Kinnard in Scotland became the first outsider to encounter the Beta Israel in the late 18th century and leave a record of it, while searching for the mouth of the Nile, their story was still the Kebra Nagast’s with a twist – that they were descended from those of Menelik’s Israelites who had not converted to Christianity. As more outsiders began to arrive in the mid-to-late 19th century, they tended to hear the same thing.

So why the lost tribe of Dan? Well, the answer lies in a stunning coincidence. Near the end of the ninth century CE, well before it is clear that there was a Beta Israel community, a man calling himself Eldad showed up in Kairouan, in what is now Tunisia, and introduced himself to the Jewish community there as a member of the lost tribe of Dan. He claimed that this tribe lived in the land of Kush, alongside numerous other lost tribes. And by that point – though not originally, since the biblical name pre-dates Aksum itself by quite some time – it was common to identify Kush with Ethiopia. The Jews of Kairouan sent this perplexing problem on to an important religious authority , the Gaon, or head of the academy, of Sura. The Gaon ruled that Eldad was who he said he was, and that his religious practice, described in a text called The Ritual of Eldad ha-Dani, was sufficiently Jewish to be accepted.

Centuries later, when Jewish outsiders began to encounter a self-identifying Jewish community in what they believed to be the land of biblical Kush, what could have been more obvious than to imagine they had discovered Eldad’s lost tribe of Dan? And as the situation of the Beta Israel drastically worsened between the mid-19th century and the mid-20th, the community was more and more willing to give at least lip service to a tradition that promised them deliverance in the form of removal to the State of Israel. Then, in 1973, when Ovadia Yosef, Chief Sephardi Rabbi of Israel, ruled that the Beta Israel were eligible to be Israeli citizens it was specifically because he believed that they were the tribe of Dan the Gaon had legitimated a thousand years earlier. In fact, the Gaon’s ruling was actually the start of a paper trail of precedent that Yosef believed himself to be following.

The reality, however, is, or at least seems to be, as Jon G. Abbink had it – that the Beta Israel, in Ethiopia, practiced “a form of indigenous Toranic Judaism… [that] occurred within the specific conditions of Ethiopian socio-political formation” (Abbink, The Enigma of Beta Esra’el Ethnogenesis, 436). In other words, it is a form of Judaism that developed in Ethiopia, in conversation with Ethiopian realities, out of shared texts and traditions but still, originally, sui generis. So, too, Hebrew Israelites represent an American indigenous Jewish tradition. In fact, as Key, Isaac, and Manasseh observe, there are “Black indigenous forms” of each of “Christianity, Islam, and Judaism that developed during both the Antebellum and post-Emancipation period [which] placed the experiences of Black folks at their center.” There are communities of Hebrew Israelites that are separate, and happy that way. And then, as I said at the beginning, there are indeed those that identify simply as Jewish and want only to be recognized as such and to live Jewish lives – which is the situation of the Beta Israel as well. Some might find the idea of an indigenous Judaism somewhere besides Israel a contradiction in terms. I can only say that it is in the nature of religions, identities, and peoples to change and change again.

Andrew Tobolowsky is Associate Professor in the Department of Religious Studies at the College of William and Mary.