The Consuming Fire: The Complete Priestly Source, from Creation to the Promised Land. UC Press, 2023.

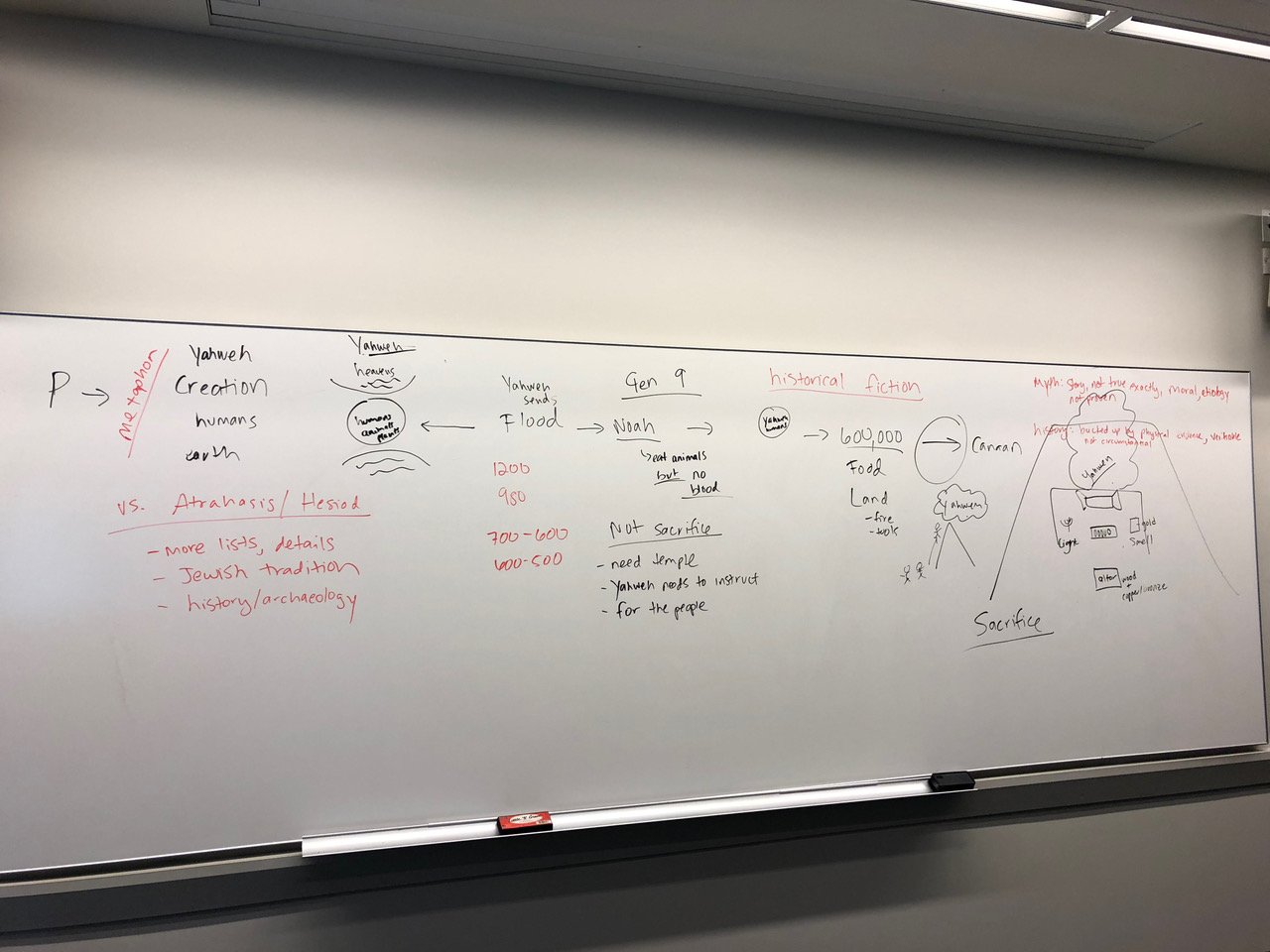

Whenever I write or talk about the pentateuchal priestly source, I find myself reiterating how important it is to understand it as a work of literature, ritual instructions and all. Most of the time my students don’t believe me at first. It takes some work to show them how the various pieces of the story fit together, how the lengthy tabernacle instructions tie in with creation and the flood, how the ritual instructions animate a static space and communicate important concepts within the story world. I often find myself standing at the whiteboard with markers charting the story arc and drawing bad stick-figure representations of key moments. I had always had this idea in the back of my head to put together a version of the pentateuchal priestly source (P) from start to finish, but it was a daunting task. When I started teaching this material, I had already spent the better part of seven or eight years working on P, refining my thoughts about its source divisions, and writing The Story of Sacrifice. Still, I had only sorted out maybe 90-95% of those source divisions; the last 5-10% were the trickiest.

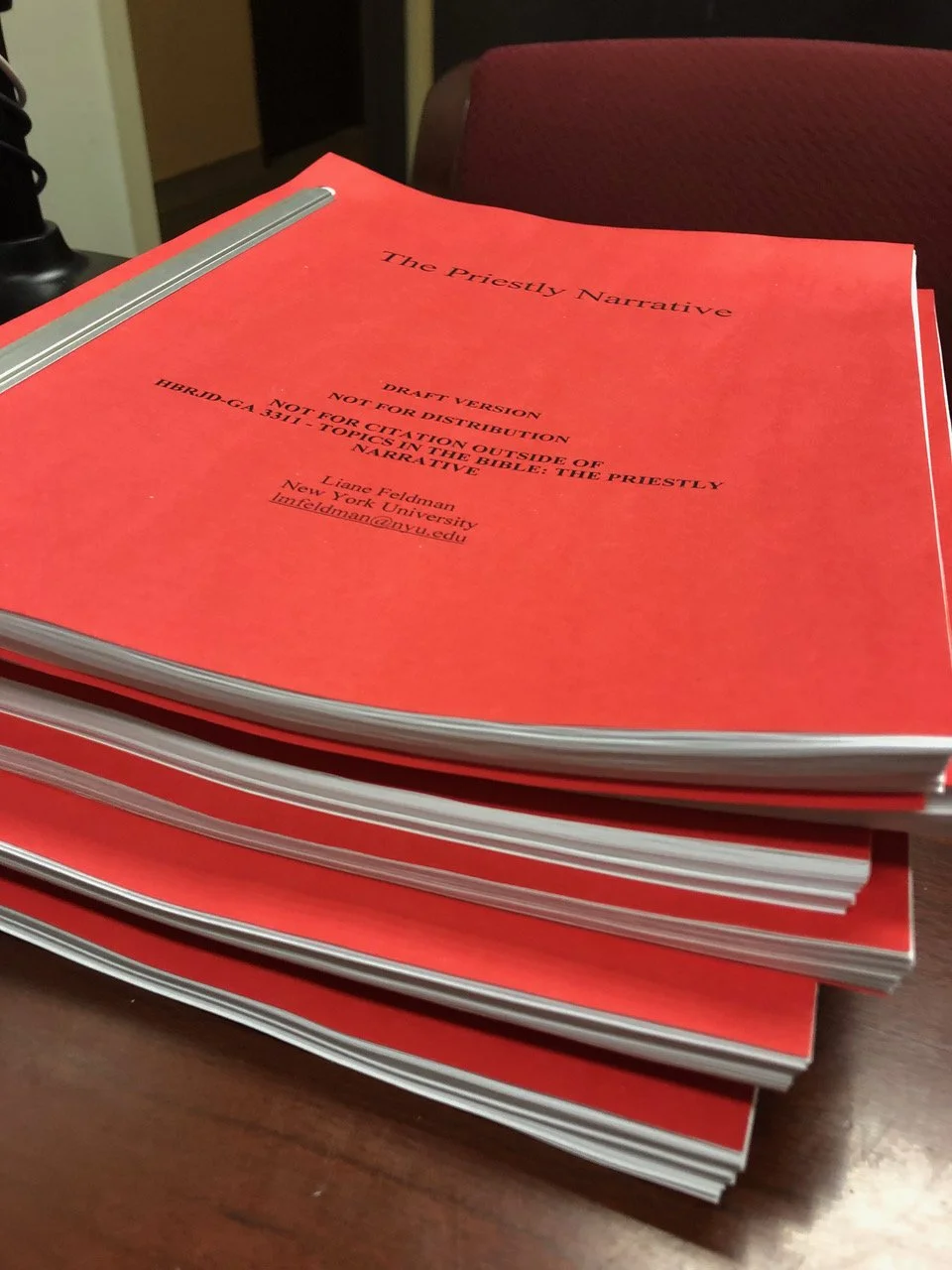

But as new professors sometimes do, I went for it anyway. In Spring 2019 during my first year teaching at NYU, I taught a graduate seminar I called “The Priestly Narrative.” The “textbook” for that course was the result of my initial attempt at putting together a full version of P in Hebrew. I made copies on the department copy machine and bound them quickly with suitably red covers. Over the course of that semester, six graduate students and I worked through the text one unit at a time while reading all manner of secondary sources and alternative reconstructions. I learned a lot that semester, but what quickly became most apparent to me was that there is so much knowledge about pentateuchal composition and P in particular that specialists have internalized. We can draw connections, see the broad story arc, spot contradictions or curiosities precisely because we have the entire picture in our minds. What also became clear to me is that as specialists, we don’t often write down that big picture. Our articles and books necessarily take on smaller segments or problems. We work to solve problems in one section of the text and publish those results in (sometimes excruciating) detail. For those who aren’t Pentateuch specialists, this knowledge can seem rather inaccessible, or at least hard to gather and assimilate. I saw this with my students that semester and I saw the difference it made for them to have a draft text they could use as a reference point.

This experience in the classroom combined with friends and colleagues regularly asking me if I had the “P version” of the flood story, the exodus from Egypt, or the plagues narrative was the catalyst for me to create The Consuming Fire. Now there are some resources out there already—the most frequently cited being Friedman’s The Bible with Sources Revealed. And as groundbreaking as that volume is for making such specialized knowledge accessible to the broader public, it has some limitations for understanding P as a work of literature. The first and perhaps most significant of these is that the volume presents a color-coded version of the entire Pentateuch. Someone who wants to gain access to “P” must pick out a particular font and color and trace that through, ignoring other parts. This can be cumbersome and distracting. Secondly, the source divisions themselves rely on an older and outdated form of the Documentary Hypothesis, largely following the work of Wellhausen, Noth, and Cross. Friedman’s volume has its strengths—especially when considering factors in the process of compilation and redaction of the Pentateuch—but it is not particularly helpful for understanding the literary profile of any given source. Anthony Campbell and Mark O’Brien have a volume that does separate the sources into individual strands, but when it comes to P they remove nearly the entirety of Leviticus—following a Nothian model that ritual and legal materials are secondary and not truly a part of the narrative.

One of my major aims in putting together The Consuming Fire was to further advance the argument I began in The Story of Sacrifice that P is not an “impoverished narrative” as has sometimes been argued. Those who have claimed this about P are also those who see the ritual instructions as secondary and “non-narrative.” But as I have argued at length, those instructions provide so much of the world-building material in this story. They are, in many ways, the cornerstone of P’s narrative. The story P tells is different from that of the nonpriestly or deuteronomic stories. P’s focus is on the establishment of the Israelite cult and the movement of Yahweh from the heavens into his Dwelling Place (mishkan) in the midst of the Israelite community. Creation and the flood in this story set up the “why”—God created the world and expected it to largely run itself. It did not. God sets up categories and distinctions in Genesis 1, most importantly that humans “rule over” the various animals, and that they can only eat vegetation. By Genesis 6, these distinctions have collapsed; animals are killing humans, humans are killing animals. The narrator tells us “God saw the earth: it was corrupt because all flesh had corrupted their assigned roles on earth” (6:12). It is at this point that P’s God sends the flood to wipe out his creation. It is also at this point that P’s God decides that he needs to be present on earth to keep a closer eye on human beings and to give them clearer rules to follow. This doesn’t happen immediately though. In order to live on earth, God needs space (land), and he needs servants (people). In the immediate aftermath of the flood, he has neither. The era of the patriarchs passes quickly in P, serving primarily to demonstrate the rapid growth of humanity and to introduce the subgroup God selects as his servants: the Israelites. This is a story that almost rushes to Sinai, passing through thousands of years in around 25 pages (in my translation, anyway). Time grinds to a halt at Sinai and the story shifts from “why” to “how”—how will God, now named Yahweh, live on earth with the Israelites? The answer is found in the elaborate tent-shrine, often referred to as the “tabernacle.” Those ritual instructions in Leviticus explain how this will be possible, how a god can live among humans. That’s the story of P—Why and how God came to be dwelling among the Israelites and what happened once he did. It’s not impoverished, but it is different. It may not conform to our modern expectations for storytelling, but it is no less literary and no less a narrative than other pentateuchal sources.

Putting the literary artistry of P on display was my primary aim in publishing The Consuming Fire. It was also the reason I chose to create a new translation of the text, rather than relying on existing ones. P has a very distinctive literary style, and much of this style can be lost when translating the Pentateuch as a whole. Intentional repetition of words and clauses, disjunctive syntax, an idiosyncratic clause structure Meir Paran termed the “circular inclusio,” and deliberate wordplay can be found across the source. Wherever I could I tried to draw these out and reflect in the English what is implicit in the Hebrew. For example, in Exodus 25:8, Yahweh tells Moses: “They will make me a sanctuary (מקדש), so that I can dwell (ושכנתי) among them.” This is the first time the root שכן is introduced in P in relation to Yahweh: in his initial declaration to live among them. Immediately after this the root appears over and over again, primarily in its nominal form משכן. This noun is typically translated as “tabernacle.” And while that translation works, it loses something important in the connection to Yahweh’s declaration in Exod 25:8. It obscures his act of dwelling among the Israelites. I’ve chosen throughout my translation to render משכן as Dwelling Place both to reiterate that connection to Yahweh’s declared intent, but also to reinforce the function of the built space within the story. I could point to dozens more examples like this across P. In dozens (if not hundreds) of articles across the last century, scholars have argued that words often have unique and specialized meanings in P. Wherever possible, I drew on those studies and translated accordingly.

Lest this project begin to sound like a gathering of esoteric academic arguments (which in a way it is), I should say that I had a strong secondary agenda in creating this translation. I wanted to make this text accessible to a broad audience. Put simply: I wanted the language and the ideas to work for an undergraduate classroom or make sense to a non-academic audience. After all, to my mind P is first and foremost a story. It should be able to be read as such. When I translated, I always did so with the non-academic audience in mind, opting for readable modern English and eschewing “bible-ese” whenever possible. The translation itself is paired with footnotes. I could have used those footnotes to explain and defend source critical choices, and at times I really wanted to do so. But instead, the focus of those notes is on highlighting literary features of the text, explaining wordplays that just don’t translate well into English, drawing connections between parts of the story, and at times offering a bit of explanatory scaffolding for the more technical portions of the narrative.

In a perfect world, I would have done both—explained every source critical decision and offer the literary commentary. The reason I didn’t was twofold. First (and most practically), the World Literature in Translation series is meant to focus on the literary facets of these texts and its volumes are meant for use in the classroom and among non-specialists. The second reason, though, is the more ideological one. My intention with this project was never to create a comprehensive, authoritative, “final” version of a source-divided P. I chose not to differentiate between strata of P in this volume, for example. In part this is in deference to accessibility for non-specialists, but in part it is also academic practicality. I myself am still not sure if I can pin down all of the various layers of this text that was almost certainly written over the course of 300+ years; it’s complicated and messy. With that in mind, I chose to create a “maximalist” version of P—including all those texts that seem broadly priestly in orientation and that build on and add to the very specific story that P tells. This is why I also included an appendix of “possible priestly materials” in the book of Joshua. It is not that I think that we can reconstruct an “original P” into the book of Joshua as it now stands. But there are threads left hanging in P’s narrative in the Pentateuch, and there are parts of the book of Joshua that seem to both build on distinctly priestly ideas and tie up some of those loose ends. Could these be the work of later editors? Absolutely. Is it possible that there was a Hexateuchal and Pentateuchal version of P? Also yes. I don’t yet know every answer when it comes to stratification of P in the Pentateuch or its continuation into Joshua. I’m also not sure that knowing those answers is necessary to create this type of maximalist text. I am certain that any specialist who picks up this book will find points to argue with. I fully expect to come back to this text in four or five years myself and quibble with a choice I made in 2021. In some ways, that’s precisely my hope for this project.

I want this book to be a starting point for conversation, and it is my hope that this is how it will be used in the classroom. The source critical project began as a conversation in a graduate seminar. I wrote its introduction with undergraduate teaching in mind, focused on as clear and accessible a summary of the methodology and priestly source as possible. I developed my theoretical approach to translation, in part, while teaching graduate seminars on the topic. Every part of this book came from or was intended for the classroom. It is my hope that it can be used in introductory level courses to introduce the priestly source, offer an example of the documentary hypothesis, or even discuss Bible translation. I imagine the current edition could be used in advanced undergraduate courses on the Bible as literature, putting P alongside Esther as a work of Israelite narrative, or perhaps in a class on ancient mythologies, reading P with Atrahasis, Enuma Elish, or the Theogony.

In the next year or so, I’ll be publishing a second edition of The Consuming Fire, this one with the Hebrew text included. This is not typically something the World Literature in Translation series does, but in this case the original text is not readily accessible. The reason I advocated for this second edition with the biblical Hebrew text was precisely so that graduate students, scholars, and even specialists could look at the original language text and continue the work of analyzing this source. Does this verse really belong in P? Where are the different strata? Is this all “P” or is some of this really “post-priestly?” How do we decide that? What was Feldman thinking with including Joshua? I genuinely hope this book can generate questions and debates in graduate seminars and among scholars. The Consuming Fire should not be the last word on reconstructing or even translating P; there’s much more work to be done.