This essay is part of a review panel of When a Human Gives Birth to a Raven that took place at the 2024 annual meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature. Read the full panel here.

Across the pages of Rafael Rachel Neis’s When a Human Gives Birth to a Raven, readers are confronted with a book as dazzlingly captivating as its title, which simultaneously perplexes and intrigues in its propositional phrasing. Throughout, we encounter an argument that feels rigorously conventional in its argumentation yet theoretically complex in the most unconventional of ways for a book that is ostensibly about the premodern past. Given the richness, complexity, and relevance of the author’s argument, perhaps the most subversive line in the entire book is that they will pursue their argument “by reading the sources ‘literally’” (21), a statement that perfectly embodies the text’s philological sophistication and the assumption-shattering approach to the material. In the end, what the author provides is an alternative to the history we know. As Rafael Neis suggests early on, in this book, they “will expose alternative ways of thinking the human and nonhuman in the writings of the rabbis” (5). This language comes to echo Jack Halberstam’s words, cited some pages later, that “dominant history teems with the remnants of alternative possibilities” (18).

In its intellectual positioning, however, the book is marked by an eschewing of analogy, as Neis describes at the end of their introduction, stating,

I do not suggest an analogy between [the book’s] contemporary stakes and ancient concern. Nor do I advocate ancient Jewish answers to present and pressing questions. In many ways my project is designed to interrupt the apparent ease with which such creative teleologies… are engineered. My hope is that confronting the otherwise thinking and being of the past can sometimes stimulate alternate ways of seeing and being in the present and for the future. (21)

This book is certainly one of “alternative possibilities,” not just in how we think about the past or make assumptions about it, but also about how we craft these arguments and the skill sets we use to approach our intellectual work.

After reading those words, for example, the reader flips the page to confront an artwork by the author: the fourth thus far, but the first since the start of the book. This one could serve as the book’s frontispiece or cover: entitled Birds Born of Humans, it affirms the proposition presented to us by the author’s title. In this photograph, we confront the animating concepts of the book as the ancient text figures forth the image of two avian forms, urging us to make formal assumptions as we taxonomize the sculpted lumps of clay. Yet, at the same time, this image reveals the author-artist’s working method: giving form in clay to a figure articulate in antiquity via that proposition, “When a Human Gives Birth to a Raven.” Here, the bird is generated through human hands, as the author figures forth their forms and documents that creation in the photograph, cunningly playing across notions of reproduction and generation.

Rafael Rachel Neis, Birds Born of Humans. Mixed media, photograph, 7.5 in. x 10in., 2020.

This image, however, embodies not only the animating question of the book, but also the methodological formulation of this text. Through the author’s artwork, we are brought back as readers to something that is inseparably contemporary to our own time, yet in its imagery and iconography we are repeatedly confronted with the particularities and granularities of the past in ways that powerfully communicate what the author is doing in this work. In spending time with Rafael’s book, I kept returning to these artworks, both as an art historian and as a medievalist. What I mean by that is that often, we pesky art historians are deeply troubled by images that appear in books yet that are neither addressed nor engaged in any substantial manner as images or as representation of a historically grounded object. Thus, these images, largely unacknowledged in the text, jarred by sensibilities.

But, as a medievalist, I could not help but be drawn to ask questions about the relationship between word-and-image, treating Rafael’s book as I might an illuminated liturgical manuscript and asking questions about the function of images: Do they illustrate the words on the page? Do they summarize the argument? Do they fill in the gaps and interstices of knowledge beyond what the text represents? Or, do they undertake some other hermeneutic or diegetic task? In asking these questions and dealing with my art-historian temporal vertigo, I began to comprehend these images not as illustrations of the text or representations of evidentiary objects, but instead as what I began to call “method-images.” These method-images punctuate the text, gripping us with their anachronicity to give representation to the argument’s methodological formulation.

At the start of the book, Rafael introduces these images, by explaining that some of their artwork has made its way into the book’s pages since, “Image-making has been central to my thinking for as long as I’ve been reading and writing.” There, they go on to explain some of the formal elements that we can find in some of the images throughout the text, such as the “hints of the marginalia gracing the fourteenth-century Duke of Sussex’s German Pentateuch and the Coburg Pentateuch,” grounding us in the premodern elements in some of the artworks (xix). Tellingly, this explanation of the images appears in the same prefatory matter that we all use to outline our sources, editions and translations, along with our translation and transliteration conventions. In this framing, the images take on a meta-narrative function, operating on the level of critical editions and transliteration conventions, as part of the largely unseen skills of the academic – much as are the various creative activities we all use to think through our work, which are often relegated to para-academic realms.

Rafael Rachel Neis, She Unnames Them ( After Ursula K. LeGuin). Mixed media, 2022.

Perhaps my favorite example of the method-image’s function comes in the chapter on “Multiplicity.” The chapter is opened by a frontispiece comic by Rafael, entitled She Unnames Them in a reversal Adam’s naming of the creatures. The comic confronts us with the critiques of Linnean taxonomy we saw in the introduction and takes part in the generative act of undoing categorical markers that is inherent to the book’s argument. As a frontispiece, the image works largely to summarize critical arguments in the chapter, much like a frontispiece in a manuscript might have a different function than an illuminated initial or a miniature within the text. In the opening words of the chapter, we read: “Otters, pigeons, ants, cows. We are struck by the plentitude of life-forms that surround us. Eagles, kittens, mice, crabs. We imagine that it falls to us to distinguish between life’s multiplicity by naming and sorting the creatures. Monkeys, elephants, unicorns, sirens” (56). If the image sought to perform Rafael’s methodological intervention in the literature, these words confront us almost with a feeling of shame, with that desire to tabulate our world and make it fit on our own accord.

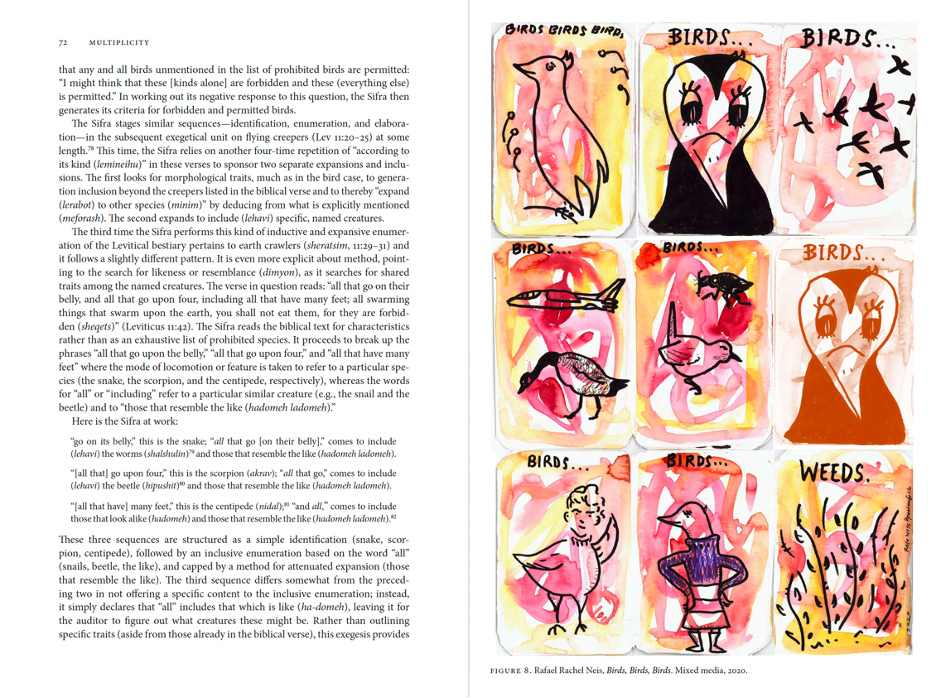

This becomes particularly poignant later in the chapter, where we are reading about sequences and enumerations of animals. On the opposite page, we find Rafael’s work, Birds, Birds, Birds, which presents us with an enumerated series of birds: First, in profile; then, frontally; then, as a flock in the sky. On the next row, we find birds again: First, a bird, yet with a figure of a plane, which is perhaps also a bird? Then, a bird, yet with some insect-like creature; and, then, a bird, the same as seen above, yet washed out. On the final row, we find some birds again: First, a bird, yet with a human’s head; then, a bird, yet with a human’s body. And, then, not birds, but weeds. In reaching this final image, the eye glances above to the first row, where the flock of birds in the sky seems to degrade in its formal recognition as such, urging us to ask if those truly are birds or just flicks of a brush that could just have easily been marshalled to be weeds. A question that was certainly being asked already by the next rectangle where the natural bird was paired with the iron bird: making us perhaps even more uncomfortable, shifting in our seats as we recognize not merely the impulse to name, but the manner in which formal judgments are repeatedly mobilized to make assumptions about the world. The artist’s hand pushes the bounds of signification until they shatter it altogether, not with birds, but with weeds: which only leads us then to ask, what makes a bird a bird?

This image has a distinctly different character than the frontispiece: telling analogous stories, but in different formulations. While the frontispiece largely took a bird’s eye view of the argument, here this picture exemplifies the method-image, operating on a parallel level to the text: seeking to mold not the reader’s understanding of the narrative, but how the reader approaches the argument of the text itself. On the next page, the text opens with meticulous timing (if we can call it that), reading in media res, “a method: a morphological gaze that scans for resemblance, and that is attenuated to the prior enumeration…” It is that morphological gaze that scans for resemblance that we have just deployed in looking at the image. While the casual reader might believe themselves to be merely admiring the artworks of the author, which they have kindly chosen to share with us, the works of art here are performing a critical conceptual labor by mobilizing and modeling the practices, behaviors, and assumptions that Rafael’s argument is inherently daring us to think beyond. The images, at times, work akin to conceptual traps, urging us to contemplate their semiotic plays and to be amused by their humor, yet also they lure us into practices of seeing and being that Rafael seeks to provide alternatives for. The image here functions not to summarize the argument, but to get us to understand it better: Or, as the paragraph’s final sentence states, in what almost seems like a tongue-in-cheek reflection of the image’s play: “As readers, we know that it is illustrative rather than exhaustive.”

In the book’s final chapter, a more conventional deployment of art-making in a scholarly text can be found. There, Rafael presents us with their drawing of Lilith, rendered from an image in the interior of an incantation bowl: a line-drawing much as we might find in an archaeological field report. While thus far the images have existed parallel to the argument, this is the first time that the author-artist uses their own work as evidence in the construction of their argument. In this portion of the text, Rafael is using the figuration of Lilith to break down, what they eloquently describe as the “epistemic pressures and constraints of a cisheteronormative gaze” that dominates the fields of Jewish studies, ancient history, and art history (181). However, it is not the figuration of Lilith in the past that is at stake here, but the figure’s figuration in the historiography. Using their own drawing of Lilith, following the incantation bowl’s image, the author-artist undoes the “sexgender dualism and the concomitant heterosexuality” that has dominated the figure’s understanding in the present.

After being confronted throughout the book with only works of Rafael’s own creation, even when they contain premodern elements, this image plays a very distinct role and, if I am not mistaken, it is the only image directly referenced in the text. As a reader-viewer, we have come to expect a certain fictionality to the author’s artworks, operating in a wholly distinct register than what we might normally find in an academic text. The Lilith image seems to betray that commitment for a more conventional positionality. Yet, I wish to argue something different: that this is not simply a clerical representation of an archaeological drawing, but another exemplar of the method-image. Line-drawings, such as these, are quite common in texts discussing incantation bowls, amulets, seals, and so on for reasons that extend beyond just the practicalities of avoiding museums’ permissions or costly reproductions.

Primarily, line drawings are deployed over photographs of the actual objects when the images they seek to represent would be poorly visible in conventional photography, either because the nature of the material medium makes the image difficult to see in a photo or because of the worn or broken condition of the image on the object. In other words, line drawings have an inherent epistemological connection with both historiographic acts of reconstruction and, most critically, with the desire for legibility. This object, however, is perfectly legible in photography.

But, is it? In analyzing Lilith through their own image, Rafael allows the reader to see Lilith anew (or, more literally), while overturning the secondary literature’s bad assumptions, embracing instead the figure’s “gender nonbinarity.” The line drawing captures Rafael’s commitment to interpret their sources “literally.” The image models the author’s thinking through images, but also the tensions that the book grapples with: namely, to present alternatives to historical narrative, while also resisting analogy with the present.

Critical to this argument, and worthy of further reflection, is Rafael’s deployment of their own artistic practice to communicate their book’s ideas and to produce a meta-argument about history and method that develops alongside the text, and does work that words alone could never do. Beyond all its groundbreaking contributions to the secondary literature, this book also presents a model for how different rhetorical forms and artistic skills can be mobilized in academic communication to reformulate how we present our arguments to our audiences, what we are able to communicate, and what audiences we can create with more varied forms of storytelling and methodological play.

Roland Betancourt is professor of art history at the University of California, Irvine.