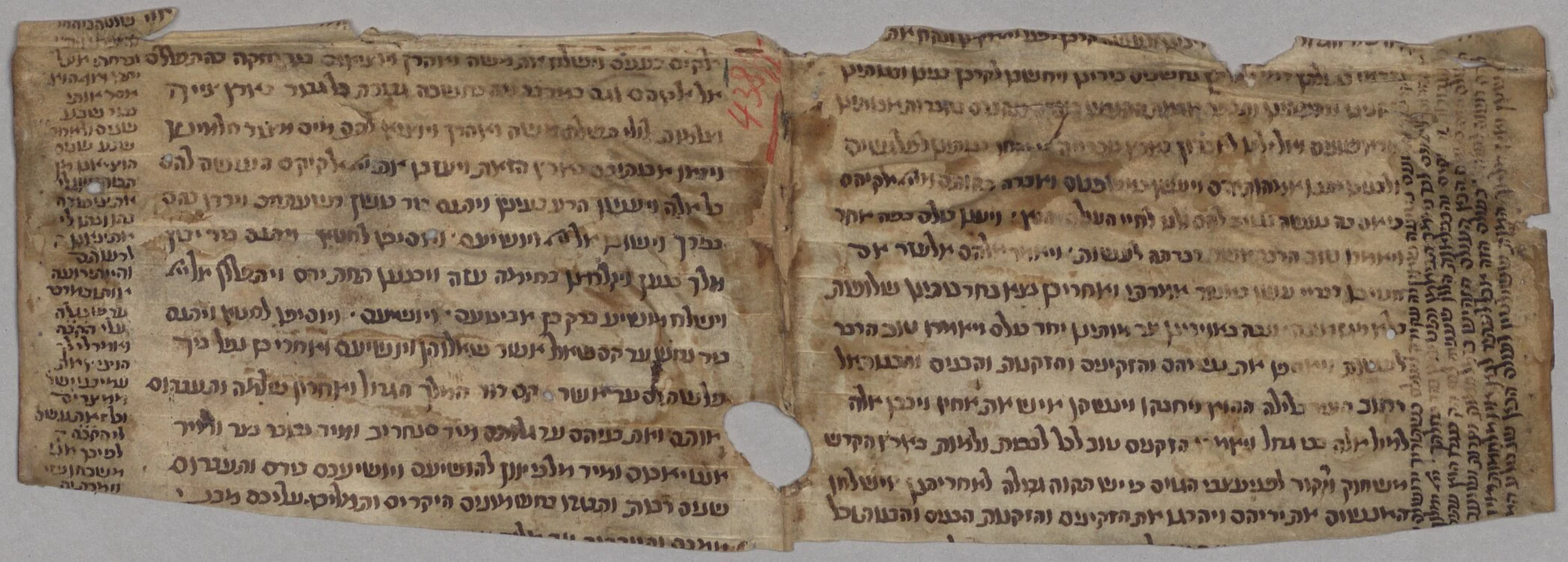

Cover page of Philadelphia Public Library, LJS 237 (ca. 1460)

In 2023 I published my first academic monograph: Biblical Heroes and Classical Culture in Christian Late Antiquity: The Historiography, Exemplarity, and Anti-Judaism of Pseudo-Hegesippus (Cambridge University Press, 2023). After giving several talks on the book (most recently with New Books Network),[i] I came to reflect upon a question: what was I trying to do with this book? And, just as importantly: what does this book actually do? While the book’s thesis and supporting arguments are specific and detailed, the overall aim of the work, I have come to realize, is much broader. The overarching goal of my work was and is to bring attention to a little-known text by pointing out several things that make it interesting and important.

The text in question is called On the Destruction of Jerusalem (De excidio Hierosolymitano, hereafter DEH),[ii] its author sometimes dubbed “Pseudo-Hegesippus.” This anonymous work rewrites Flavius Josephus’ Jewish War (written c. 75 CE) as a kind of paraphrase for a Latin-reading, Christian audience probably in the later 4th century (maybe 370-375 CE). Because it is based on this earlier, ‘original’ Greek work, this Latin history has received markedly short shrift in contemporary scholarship (though not in the broader history of research, as we shall see). But I think that this work should be known to and studied by scholars of ancient Judaism, early Christianity, biblical studies, and Classics (e.g.). Hence this essay for AJR, which attempts to do something that is the polar opposite of David Letterman’s popular talk show, “My Next Guest Needs No Introduction.” Among scholars today, Pseudo-Hegesippus absolutely needs an introduction; very few people know what DEH is. Let this short essay serve then as an introduction to this unknown guest and as an argument for more attention to be paid to DEH by scholars.

Pseudo-Hegesippus was a supersessionist project par excellence. DEH codifies like no other text the early Christian enthusiasm for and appropriation of Josephus’ works for its own apologetic-historiographical ends. The work’s author rewrites the history of Jerusalem’s destruction in order to clarify what was already the de facto Christian position: the downfall of Jerusalem and its Temple represented divine chastisement precipitated by the Jewish rejection of Jesus as messiah. DEH relies self-consciously upon Josephus’ narrative to fashion his version of events, yet he also finds utility in Josephus’ continued identification as Iudaeus. Thus, while Josephus was an excellent historian, DEH posits that he had not understood the cause of Jerusalem’s destruction (causam aerumnae non intellexit; Prologue 1). While he faithfully recounted (albeit briefly) Jesus’ effective ministry, he did this not truly believing his own words (ut nec sermonibus suis crederet), but only because he was unwilling to lie about historical events (DEH 2.12.1). Josephus, in DEH, retains the classic pockmark of Jewish duritia cordis (“hardness of heart”). Such rhetorics are by now very familiar to scholars of Jewish-Christian engagements in late antiquity. DEH is a source of central importance for this area of study: it is one of the earliest, lengthiest (the text is about 88,000 words), and most influential articulations of the anti-Jewish Christian historiographical imagination in late antiquity. Yet DEH remains a rare appearance in studies of anti-Jewish rhetoric and/or Jewish-Christian discourse in late antiquity.

DEH tends likewise to be underrepresented in the study of the reception of Classical and biblical texts. Yet the text betrays unique treatments of vocabulary and phraseology from authors like Vergil, Horace, and Sallust (indeed, DEH is modeled as historiography on the latter). It provides hundreds of data-points for the study of biblical reception, which can be put into profitable conversation with rabbinic texts, other early Christian literature, early Bible-adjacent writings, and so on. In fact, the primary thesis of my book, Biblical Heroes and Classical Culture in Christian Late Antiquity, is that the scriptural figures brought to the fore in DEH—almost exclusively from the Hebrew Bible, so the author’s Old Testament—evince the author’s habituated engagement with the distinctive Roman discourse of exemplarity. This argument, moreover, situates DEH within the classical tradition of historiography hailing back to Herodotus, Thucydides, and Xenophon, making Pseudo-Hegesippus a multifaceted resource for studying the Christian/Jewish/Roman interface of late antiquity. DEH constitutes a discernible Christianization of the classic Greco-Roman model of historiography (far more so than Eusebius, Orosius, or any other late antique Christians), an unusual classicization of the nascent Christian industry of history-writing (no other Christian historians of the time wrote war monographs about non-Christian peoples), and a remarkable Judaization of Latin literature (not only are most of the narrative’s actors Judeans, but the work’s many digressions involve Jewish ritual, society, and tradition, albeit from a self-consciously Christian perspective). Other groups of scholars who should know about DEH include those who do biblical or classical reception history and those who study ancient historiography.

Students of apocrypha and pseudepigrapha can also find interesting material within DEH. The one place that Christian actors appear in the narrative, the so-called Passio Petri et Paul (DEH 3.2.), recounts a distinctive iteration of Peter’s and Paul’s martyr stories, including a version of the highly entertaining episode in which Simon Magus uses a flying contraption and is prayed out of the sky by his arch-nemesis Peter. I have recently produced a translation of this passage for the third volume of Tony Burke’s New Testament Apocrypha series. (I am also currently working on an English translation of the entire work with George Woudhuysen for publication in the Translated Texts for Historians series of Liverpool University Press.) As a long text with diversified content and interesting language, DEH has something for everyone.

Within the study of Josephus and his reception, Pseudo-Hegesippus tends to be relatively well known. At roughly the same time as DEH was written—sometime in the later 4th century, but possibly even the early 5th—Josephus’ Jewish War was also being translated into Latin (and Syriac, apparently, but that is another story). Thus, by the 5th century there existed both a rather literal 7-book translation of Josephus’ Jewish War into Latin (Josephus’ Greek work was also in seven books) and DEH, a condensed, Christianized, and classicized 5-book version of the Jewish War. Josephus’ 20-book Jewish Antiquities would not be translated into Latin until the middle of the 6th century, under the watchful eyes of Cassiodorus at his Southern Italian monastery, the Vivarium. DEH thus belongs to a collection of full-length works that testify to the Christian enthusiasm for Josephus’ histories in late antiquity. Yet, unlike the Latin War and Latin Antiquities, DEH exudes a conspicuous overlay of Christian ideology. Thus, while reworking Josephus’ description of the Jewish Temple, Pseudo-Hegesippus will write that there existed “an idea of the Trinity” (cognition Trinitatis) within the former Temple’s inner sanctuary (DEH 5.9.4). Perhaps the most fascinating feature of this work’s Christianitas is that it puts both Christian ideas and Christian Scriptures into the mouth of one of its most active narrative characters: Josephus himself. Thus, in DEH 5.31.2 Josephus will identify Jerusalem’s destruction as the “abomination of desolation” (abominatio desolationis) prophesied in the Book of Daniel (11:31; 12:11) and picked up by the New Testament Evanglists (Mark 13:14; Matthew 24:15). Elsewhere, language from the letters of Paul will crop up in Josephus’ orations. Not only, therefore, is DEH an important text-critical and traditional-critical resource for studying Josephus’ texts and their reception, it also proves interesting in its use of Christian language and concepts to rescript part of Josephus’ life. DEH thereby appears as one of the most biographically active treatments of Josephus—one of late antique Christianity’s absolute favorite authors, remember—in antiquity (and, indeed, of all time).

DEH’s own Rezeptionsgeschichte is likewise notable. Counting both complete codices and fragments of various lengths, DEH survives in over 200 manuscripts, which is more than those of the Latin translations of Josephus’ Jewish War and Jewish Antiquities (surviving in 146 and 174 manuscripts respectively). The earliest date to the 5th or 6th century. DEH also became the basis of numerous later works: on the Christian side, DEH 5.2 was the foundation for an anti-Jewish Latin Eastern Sermon called the Anacephalaeosis or Recapitulatio (often “Pseudo-Ambrose”), the even more trenchantly anti-Jewish Vindicta Salvatoris, and at least one later highly-condensed version (in ms Würzburg M ch f 128, ca. 1500, the youngest manuscript I have found); on the Jewish side, DEH became the primary source for Sefer Yosippon, an early-10th century Hebrew work that effectively reclaimed Second Temple history for an early medieval Jewish readership (the topic of my present book project). This latter work itself became one of the most popular Jewish historical texts of all time, being expanded, copied, and translated energetically over the past millennium.

Fragment of a Yosippon manuscript (c. 14th cent.). Holding institution: München, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. Call number: Cod.hebr. 153(8. Digitized by Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. Link: https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/en/view/bsb00039620?page=4,5

The exceptional influence and popularity enjoyed by DEH from late antiquity through the Middle Ages, and its critical interface with Jewish historiography as a work both based on and source of major Jewish histories, suggest that this work is important for scholars of pre-modern Judaism and/or Christianity to know. DEH’s afterlives represent a treasure-trove of literary-historical data for studying the (largely conceptual) Jewish-Christian interface in premodernity. Perhaps most interesting of all is that DEH commanded concerted and widespread attention from readers, Christian and Jewish, starting just decades after the penning of the work up through the early-20th century, when scholarly interest fizzles out. It became the basis for histories in Hebrew, Arabic, Judeo-Arabic, and Ethiopic, was a major source for medieval Slavonic historiography, and was translated into Italian (1544), French (1556), German (1574) within a century and a half of the invention of the printing press. Not to put too fine a point on it, effectively everyone knew about this work in the Middle Ages, and even more recently, Vincenzo Ussani’s standard critical edition (1932) replaced an edition that was already more than fifty years old (printed in 1864) and was quickly followed by several dissertations (in 1932 and 1935) from the Catholic University of America. The question is not so much why DEH was so popular historically but how such a conventionally well-known text came to be effectively unknown among scholars today.

My book is the first English-language monograph to engage with DEH. Before that, an Italian monograph by Chiara Somenzi had appeared in 2009,[iii] and two unpublished dissertations in English and French had emerged in 1977 and 1987 respectively.[iv] (In the past year, the first German monograph on the work has come forth, resurrecting a longstanding debate as to whether or not Ambrose of Milan penned DEH.)[v] Other than that, while medievalists and Josephus specialists have paid sporadic attention to DEH—Richard Matthew Pollard’s 2015 VIATOR article has been particularly often-cited[vi]—Pseudo-Hegesippus remains a largely unknown entity.

For that reason, I thought that Pseudo-Hegesippus deserved a modern, re-introduction to scholarship in the 21st century. My hope is that students and scholars of Jewish-Christian relations and the tradition of anti-Judaism, of biblical interpretation and reception, of Latin literature, of Josephus’ influence, of late antiquity more broadly, and of many other salient areas of study will keep DEH in mind when surveying texts and thinking through the worlds that Pseudo-Hegesippus may help illuminate.

Carson Bay is a Research Associate at the Institute for Advanced Study - Princeton.

[i] For these opportunities, I am grateful to Tobias Joho and the altphilologische Forschungskolloquium der Universitäten Basel, Bern, Freiburg i.Br., for which I gave a book talk in Freiburg im Breisgau on November 4, 2022, and to Andreas Klingenberg and Universität Köln, within whose Forschungskolloquium Alte Geschichte I gave a book talk on May 11, 2023.

[ii] Bay, Carson. 2018. “The Bible, the Classics, and the Jews in Pseudo-Hegesippus: A Literary Analysis of the Fourth-Century De Excidio Hierosolymitano 5.2.” PhD Dissertation, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL.

[iii] Somenzi, Chiara. 2009. Egesippo – Ambrogio: Formazione scolastica e cristiana a Roma alla metà del IV secolo. Studia Patristica Mediolanensia 27. Milan: Vita e Pensiero.

[iv] Bell, Albert A., Jr. 1977. “An Historiographical Analysis of the De Excidio Hierosolymitano of Pseudo-Hegesippus.” PhD Dissertation, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Chapel Hill, NC; Estève, Dominique. 1987. “L'Oeuvre historique du Pseudo-Hegésippe: "De Bello iudaico", livre I à IV.” ELP 10; PhD Dissertation, Université Paris Nanterre. Paris, France.

[v] Zwierlein, Otto. 2024. Das >Bellum Iudaicum< des Ambrosius. UALG 157; Berlin: De Gruyter.

[vi] Pollard, Richard Matthew. 2015. “The De Excidio of ‘Hegesippus’ and the Reception of Josephus in the Early Middle Ages,” VIATOR 46: 65–100.