The author’s conclusions led me to wonder about an angle of comparison that had been addressed only obliquely: Are the commentary texts from Mesopotamia and Qumran actually doing the same kind of commenting? Should the function of a text affect the generic comparisons we make with it?

Read MoreReview | Heirs of Roman Persecution: Studies on a Christian and Para-Christian Discourse in Late Antiquity

Even after Christianity attained hegemony in the late Roman empire, accounts of persecution at the hands of the impious appear frequently in the historical record. In fact, late ancient authors continually mobilized what the volume calls the “discourse of persecution” throughout the late ancient Mediterranean to various ends. That discourse and its many manifestations form the volume’s object of inquiry.

Read MoreBook Note | Beyond Orality: Biblical Poetry on its Own Terms

Overall, then, Vayntrub’s study is a timely and incisive contribution to the study not just of biblical poetry, or of representations of oral speech in biblical literature, but of what many biblical traditions fundamentally are and reflect.

Read MoreBook Note | The Wandering Holy Man: The Life of Barsauma, Christian Asceticism, and Religious Conflict in Late Antique Palestine

Composed in Syriac, the Life of Barsauma offers new resources for understanding the construction of holiness in late antiquity.

Read MoreBook Note I Slavery, Gender, Truth, and Power in Luke-Acts and Other Ancient Narratives

Christy Cobb, Slavery, Gender, Truth, and Power in Luke-Acts and Other Ancient Narratives (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave MacMillan, 2019)

In the preface to Slavery, Gender, Truth, and Power in Luke-Acts and Other Ancient Narratives, Christy Cobb presents an image of a 19th century shovel, produced according to its label by a “female slave and blacksmith on the Cobb family farm” around 1850 (viii). Cobb notes that this artifact of enslavement in her family history serves as the impetus for this book; she seeks to open up the historical record and bring to light the truth-telling power of three enslaved women in Luke-Acts: the woman in the courtyard who recognizes Peter as a disciple of Jesus in Luke 22: 47-62, Rhoda, enslaved of Mary, who answers the door to find Peter freed from incarceration in Acts 12, and the divining slave of Acts 16. Cobb deftly combines the literary theory of Mikhail Bakhtin with feminist biblical hermeneutics, arguing that these enslaved women are “focalizors” in Luke-Acts who speak truth to power despite their doubly marginalized status as both women and slaves (63).

Chapter 1, “Introduction: (Re)Turning to Truth,” situates the enslaved women of Luke-Acts within a broader historical and literary landscape. Cobb utilizes a wide range of materials, necessary given the sparse evidence for the circumstances of the enslaved in antiquity. Drawing on Page duBois’ Torture and Truth, Cobb shows how the bodies of the enslaved were 1) subject to corporeal punishment; and 2) conceived as unable to tell the truth except under duress. Luke-Acts, however, renders it differently. In Cobb’s view, while truth and logos were indeed often understood to be the exclusive property of free male subjects, truth here “is found in the ‘other’”, that is, “in the words of three female slaves” (10). To get to this point, Cobb grapples with the Glancy-Harrill debate: the question of whether it is possible to arrive at such conclusions, given that elite perspectives overwhelmingly mediate our access to the experiences of the enslaved. In the end, Cobb concurs with Glancy in that, while our sources are biased, it is still possible to glean historical evidence from the representation of slaves in literary sources, particularly when literary and archaeological sources are read side by side. Furthermore, Cobb asserts that a Bakhtinian lens (explained further in the next chapter) allows for greater recognition of moments in which enslaved figures exceed or counteract the constraints of their representation, speaking outside the aims or desires of the author.

Chapter 2, “Theoretical Foundations: Bakhtin and Feminism,” outlines the theoretical framework of the book. After delineating the theoretical vocabulary structuring her analysis (menippea, the novel, the role of the author, outsidedness, polyphony and dialogism, carnivalesque, and heteroglossia), Cobb addresses the thorny question of engaging Bakhtinian theory and feminist hermeneutics side by side given Bakhtin’s infamous lack of attention to issues of gender (73). In response, she notes that feminists have made productive use of Bakhtin’s body of work in literary studies. Julia Kristeva’s theory of “intertextuality,” developed in conversation with Bakhtin’s work on dialogue and ambivalence, argues that texts are interconnected through the polyphonic and citational nature of textual “utterances” (74-77). While Kristeva does not outrightly claim her work as feminist, Cobb highlights that intertextuality as a theoretical and hermeneutical tool has been influential in feminist and postcolonial circles (77). She concludes that just as Bakhtin’s work sheds new light on Luke-Acts, so also does feminist theory enhance and refine Bakhtin’s analysis of power. Here, Cobb’s analysis turns our attention to the ways in which theoretical frameworks are not isolated entities but stand in dialogic conversation.

The next three chapters analyze the text of Luke-Acts, connecting the three enslaved women truth-tellers to one another and to their counterparts in contemporaneous ancient texts and material culture. In Chapter 3, “The One Who Sees: Luke 22:47-52,” Cobb argues that the unnamed enslaved woman in the courtyard becomes a ”focalizor” of truth and a “mouthpiece of Lukan theology,” whose statement of truth defines Lukan discipleship as those who are “with” Jesus (82). In the famous scene of Peter’s denial of Jesus, Cobb attends to the slave girl (paidiske), who identifies Peter with a withering gaze and names him as one who was “with” Jesus despite his pleading to the contrary. Cobb notes that in each version of this scene in the Gospels, it is the slave girl who recognizes and names Peter. In so doing, the slave girl pushes the boundaries of her marginalized status in the elite space of the courtyard and in relation to the free men around her (89).

In order to provide context both for the circumstances of enslaved women in elite households and for the relationship between slavery and truth, Cobb turns to an intertextual reading of Chariton’s Callirhoe (93-100). Cobb also highlights the powerful and prophetic nature of the gaze of the enslaved by placing Luke in conversation with the flute-player Acts of Andrew (110). When she turns back to the paidiske in Luke 22, Cobb argues that, positioned near the light which further indicates her truth-telling power, the enslaved woman “provides a clear definition for discipleship, even amidst Peter’s betrayal” (112). Bakhtin’s polyphonic dialogism is at work here; the narrative gives equal weight to the two competing perspectives of Peter and the enslaved wo/man even as the reader knows all along that the slave’s witness is the truthful one.

In Chapter 4, “The One Who Answers: Acts 12:12-19,” Cobb develops a portrait of Rhoda as much more than a parodic servus currens (running slave) in the narrative of Acts. Rather, she is a truth-teller situated at a pivotal point in the narrative where the focus shifts from Peter to Paul. Cobb then reads Rhoda’s scene in Acts alongside the torture and truth-telling of Euclia in the Acts of Andrew in order to draw out elements of the carnivalesque in both narratives. In each case, though to differing extremes, categories of social power are (temporarily) upended and the enslaved emerge as special bearers of truth and knowledge over against those in power. Rhoda’s recognition of Peter at the gate signals a carnivalesque turn in Acts, as she is placed in a position of superior knowledge of the truth in relation to the free persons who reject her claims. As Cobb writes, “The climax of this Bakhtinian carnivalesque moment occurs in the doorway of Mary’s house, not inside yet not outside, as the hierarchies within the text (female/male; slave/ free; minor character/apostle) are suspended and the most marginalized of all the characters emerges a truth-teller” (149). While Euclia is represented in Acts of Andrew as a stereotypically deceitful and licentious slave, she is able to masquerade as a free woman for several months and her successful performance reveals the fluid boundary separating free and enslaved. In the end, she tells the truth of Maximilla’s plot and, while she pays for it with her life, she also reveals herself to be more truthful than her enslaver (161). In both texts, the axis of power returns (violently, in the case of Acts of Andrew) to the elite, but Cobb argues that the emergence of Rhoda and Euclia as truth-tellers poses an ongoing challenge to the notion that the enslaved do not possess the logos to speak the truth.

In Chapter 5, “The One Who Prophecies: Acts 16:16-18,” Cobb argues that the much-discussed divining slave of Acts 16 should be engaged through the lens of Bakhtinian heteroglossia, or the use of “another’s speech in another’s language, serving to express authorial intentions but in a refracted way” (164). Her prophetic words ring true in the narrative and she, like the slave in Luke 22:47-52, becomes a mouthpiece for Lukan theology. Cobb contrasts this unnamed slave woman with Lydia of Thyatira in order to emphasize the “outsider” status of the enslaved woman when compared to Lydia’s influential role as an “insider” in the narrative. This “outsider” status gives her a unique perspective from which to see and speak the truth of Paul and Silas, at great cost to the enslavers who used her prophetic power for profit. Cobb also uses evidence from literature and material culture to connect the truth-telling power of the unnamed slave girl to powerful oracular figures in Delphi and elsewhere in the Greek world. Cobb understands the slave girl’s claim that Paul and Silas are “slaves of the Most High God, who proclaim the way of salvation” (Acts 16:17) as heteroglossia, encompassing multiple meanings as the “Most High God” can be “the God of the Hebrew Bible, the God of Paul and Silas, and even the God of the slave girl” (192). Furthermore, the identification of Paul and Silas as “slaves” not only echoes Paul’s use of the discourse of enslavement in his letters but also foreshadows the treatment that Paul and Silas receive at the hands of the authorities later on in Acts 16. In a close reading of each element of her prophetic statement, Cobb sees truth that unfolds as the narrative progresses.

Each of the enslaved women that Cobb analyzes in this book speaks truth to power, despite the risks inherent to doing so from their position as enslaved women. Cobb very effectively utilizes the polyphonic, menippean nature of Luke-Acts to connect these women not only to one another but also to other voiceless enslaved women in ancient narratives. Perhaps the greatest contribution of this book is its use of intertextual analysis to demonstrate that the distinction between enslaved and enslaver was not as clear-cut as those in power wished it to be. In speaking their truth, the enslaved women addressed in this volume challenge the boundary between free and enslaved, revealing the great lengths to which ancient writers must go in order to construct and naturalize these categories.

Bringing feminist biblical interpretation in conversation with Bakhtinian literary theory, Cobb’s work is itself polyphonic. While tense at times, bringing these areas of inquiry into conversation allows for the voices of the enslaved women in Luke-Acts to rise to the surface in new and exciting ways. This book will be of great interest to those interested in the intersections of gender and enslavement but also as a model for using theory not just as a tool to reconstruct the past but as a way to engage the past in the service of justice and truth-telling in the present.

Kelsi Morrison-Atkins is a ThD candidate in New Testament and Early Christian Studies at Harvard Divinity School, Kelsi_morrison-Atkins@mail.harvard.edu.

Book Note | Cosmos in the Ancient World.

Cosmos in the Ancient World brings together an interdisciplinary set of essays on the Greek concept of kosmos, and its Latin translation mundus, in Greco-Roman literature, philosophy, and visual culture.

Read MoreBook Note | The Temple in Early Christianity: Experiencing the Sacred

Regev’s The Temple in Early Christianity is a highly organized and comprehensive discussion of Temple and Temple-related themes in the New Testament.

Read MoreBook Note | Demons, Angels, and Writing in Ancient Judaism

Reed’s book highlights what might be finally termed a true period of the scribes: a time during which literature was produced not only by scribes but about them and for them, highlighting their special status and privileged lineage.

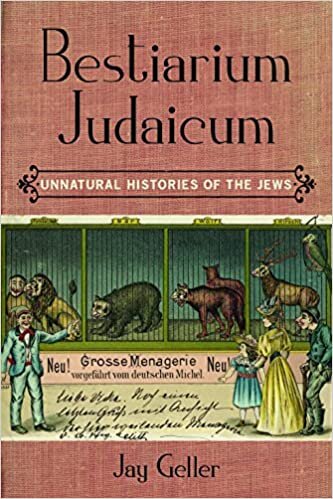

Read MoreBook Note I Bestiarium Judaicum: Unnatural Histories of the Jews

Jay Geller, Bestiarium Judaicum: Unnatural Histories of the Jews (New York: Fordham University Press, 2018)

In recent years, a growing interest with critical animal studies has challenged fields to reflect upon anthropocentric arguments and assumptions based on the Cartesian human-animal hierarchy. Bestiarium Judaicum is Jay Geller’s response to this challenge. Geller splices his academic interest on Jewish identity and embodiment with the question of the animal, or more precisely, “the Jew and the animal” (7). Working with the perspectives of Jacques Derrida and animal studies’ proponents such as Mel Chen, Donna Haraway, Kelly Oliver, and Cary Wolfe, Geller interrogates the presence of more-than-humans (a politically correct umbrella term for animals, plants, and inanimate entities) in texts produced by German-Jewish authors who wrote during what he calls the “the Era of the Jewish Question,” which is roughly from 1750 to the Shoah (5).

The animalization of Jews or, as Geller calls it, “Jew-Animal,” during this period is not just a one-off canard or ethnic banter meant to tease or ridicule. Rather, it responded to a “collapse of the religious and the lineage/corporate (estate, guild, and so on) narratives of value and meaning and of the institutions that sustained them amid the social destabilizations, geographic relocations, colonial expansions, economic destabilizations, and increasing bureacratizations that were also occurring” (5). As some Germans tried to build the walls of their identity markers, they found various Jewish groups’ (and other minoritized groups) concomitant goal to integrate to the national German identity disturbing and even repulsive. In order to invent their identity, the Germans had to have the “other.” They did so with animalizing rhetoric, in accordance with which the Jews are “disgust (worms), threats (beasts of prey), ridicule (apes, pigs, goats, parrots),” and other negative associations (47). The animalization of the Jews manifests a narcissistic lack stemming from Germany’s unstable national identity (47). Moreover, hate-filled bourgeois Germans were even concerned that such integration, based on the negative stereotype that the Jews are highly capable of mimicry, would deter their goal for “some form of pure völkisch identity” (117). Thus, they depicted Jews as animals, including apes, in an attempt to prevent Jews from assimilating into the German fold.

Re-reading German-Jewish authors through the lens of animal studies, Geller finds a counter discourse that disrupts this formula of human hierarchy and exceptionalism. These German-Jewish authors did not defend or justify their humanity by distancing themselves from more-than-humans. Rather, they wrote with more-than-humans, multiplying and destabilizing the taxonomic limitations imposed between Jew-Gentile/animal-human to format a “Jew-as-Animal.” As in Franz Kafka’s work, for example, Geller finds a proliferation of more-than-humans, sometimes even anthropomorphized. He understands this to reveal the constructed nature of Jew-Gentile/animal-human differences, substantiating the argument that identities are not essential (or given) but constructed (58). Such constructions are interpellations by the oppressive dominant force in Germany that tries to subjugate the Jews by animalizing their identity. The “as” of “Jew-as-Animal” both associates and dissociates Jews from/with animals, blurring ontologies by multiplying their relationality. These literatures expand the interpellation indefinitely as a way of exposing the debasing essentialist rhetoric present during that period (137). “Jew-as-Animal” denaturalizes the artificiality of Jew-Gentile, human-animal divide, by demonstrating through literature that “Jewishness does not exhaust one’s identification, nor does one’s identification exhaust the possibilities of Jewishness” (26).

We find examples of this reasoning throughout Geller’s analysis of the various animot, a Derridean neologism that questions the perceived lack of responsivity of more-than-humans. He reads it in the works of Franz Kafka (The Metamorphosis, Josephine the Singer, Two Animal Stories, and Red Peter from A Report to an Academy), Heinrich Heine (Travel Pictures and “Aus der Zopfzeit”), Felix Salten (Bambi), Salomon Maimon (An Autobiography), and Art Spiegelman (Maus: A Survivor’s Tale), to name a few. Geller reads Kafka’s Red Peter, for instance, not just as an ape. Kafka has Red Peter respond to his environs through representation, voice, and agency. Red Peter might be self-deluded, but such complexity of character makes Red Peter “more human.” Kafka’s intent, as perceived by Geller, is to bring the Jewish community out of objectification and animalization by interpellating with more-than-humans. Red Peter is the Jewish animot (137) who is identifiable and yet ungraspable, reproduced and yet different in every iteration.

Geller is realistic in his take on the “end game” of such deconstruction: “For Kafka, such a strategy would neither negate the demeaning identifications nor render them benign; nor would it lead to a reversal of the hierarchical power relations. But it might mitigate the murderous affect aroused by contact with the monstrous animal-object constructed by the dominant society’s own fears, hatreds, and identification practices as well as defer the deadly transformation of analogy into identity – to render the Jew as animal and therefore killable” (187). Here, Geller taps into Derrida’s discourse on “killable” in which the consumption of the other for food/survival is not the issue. Rather, the problem is when one perceives the other as “killable,” or the necro-politics in which the Other is only meant for death or dispensability.

Geller could have worked further on works beyond those of Kafka and Heine. Other authors are crammed in the last chapter and the Afterword. Even the discussion on the Shoah in the Afterword might have been given further space in the book, since that is something general readers of Geller’s work would immediately recognize. Speaking of recognition, Geller’s close reading of his chosen texts are sometimes so specialized that those unfamiliar with the texts might get lost quickly. Geller also focuses on critique of certain scholars rather than background discussion. General readers of this book might need significant assistance in grasping the contours of the argument.

Overall, Geller argues that German-Jewish authors of this period did not hate themselves or internalize anti-Semitism just because they worked with more-than-humans in their literatures. There could be a way to be in solidarity with all of creation while fighting for one’s humanity. There are ways to combat racism without falling into the trap of speciesism, making it even more urgent to find ways to be in solidarity without negation or replacement.

Dong Hyeon Jeong is Assistant Professor of New Testament Interpretation at Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary. He is also a board member of the Center and Library for the Bible and Social Justice. His forthcoming book is entitled, With the Wild Beasts, Learning from the Trees: Animality, Vegetality, and (Colonized) Ethnicity in the Gospel of Mark.

Book Note | Augustine and the Dialogue

Drawing on literary theory, Kenyon explores the dialogues with an eye to their pedagogical features, allowing the dialogues to be read “on their own terms.”

Read MoreBook Note | Constantinople: Ritual, Violence, and Memory in the Making of a Christian Imperial Capital

Falcasantos’ Constantinople demonstrates how change and continuity stood in tension in late antique Constantinople.

Read MoreBook Note | Egyptian Hieroglyphs in the Late Antique Imagination

Egyptian Hieroglyphs in the Late Antique Imagination is a broad-ranging and accessible treatment of how late ancient writers engaged with pharaonic history and culture in the midst of the Christianization of Egypt.

Read MoreBook Note | The Jerusalem Temple in Diaspora: Jewish Practice and Thought during the Second Temple Period

In The Jerusalem Temple in Diaspora, Jonathan Trotter offers a new reconstruction of the relationship between diaspora Jews and the Jerusalem temple that is both grounded in lived practices and informed by literary analysis.

Read MoreBook Note | Humor, Resistance, and Jewish Cultural Persistence

How can we account for the seemingly contradictory perspectives of responses to empire and imperial subjugation in the Book of Revelation? Through the lenses of humor studies and trauma theory in postcolonial discourse, Sarah Emanuel’s innovative work addresses this question and demonstrates how comic is used as a mode of survival for the Jewish community of John’s Apocalypse.

Read MoreBook Note | Self-Portrait in Three Colors: Gregory of Nazianzus’s Epistolary Autobiography

Storin’s work, both monograph and translation, marks another excellent entry in the UC Press Christianity in Late Antiquity series. Taken together, these volumes will prove valuable not only to scholars of Gregory or ancient epistolography, but all those interested in the interdependent constructions of rhetoric, philosophy, and the self in late antiquity.

Read MoreBook Note | Between Mishna and Midrash

“Close reading, suggests Rosen-Zvi, resembles micro-historical study since in both cases a close look at one detail reveals large social and cultural processes that cannot be seen from a wider perspective.”

Read MoreBook Note | Enoch From Antiquity to the Middle Ages

…[O]ne of the most valuable contributions are the plentiful insights throughout this volume that have implications for a wide variety of fields, ranging from antiquity to the medieval period. And, while there are no doubt plentiful insights with regard to Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, a number of observations throughout this work also hold implications for the field of Ancient Mesopotamian religion and its relation to later traditions.

Read MoreBook Note | Time in the Babylonian Talmud

Kaye suggests that time as imagined in the BT is best represented by Wassily Kandinsky’s painting, Several Circles (1926). According to Kaye, the painting’s circles of various sizes and colors represent various moments; these moments, as circles, interact both temporally and spatially and are spread across the canvas non-linearly.

Read MoreBook Note I Growing Up in Ancient Israel: Children in Material Culture and Biblical Texts

Book Note | When Christians Were Jews

Paula Fredriksen’s newest book attempts a difficult feat: to understand the first generation of Jesus followers, despite having to do so with an eclectic smattering of passionately biased evidence that also happens to have been cherished as sacred text by almost two thousand years of interpreters.

Read More

![Bohumil Kubišta, Kiss of Death (1912) [Wikimedia]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5449167fe4b078c86b41f810/1622990626830-7MX8BLM1FHUSMDV1EQQ1/344px-Kubista%2C_Bohumil_-_Polibek_smrti_%281912%29.jpg)

![Painting from the Dura-Europos synagogue [Wikimedia Commons]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5449167fe4b078c86b41f810/1609961660658-32CNYME54TMXKQ6UQT6I/512px-Herod%27s_Temple.jpg)

![Gioacchino Assereto, Saint Augustine and Saint Monica (17th c.) Minneapolis Institute of Art [Wikimedia]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5449167fe4b078c86b41f810/1605971002733-9D18XXO9KQN78R69SI5J/Gioacchino_Assereto_-_Saint_Augustine_and_Saint_Monica_-_60.35_-_Minneapolis_Institute_of_Arts.jpg)

![Ivory plaque featuring scenes from the story of Joshua, Byzantine (900-1000 CE) [MET Museum].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5449167fe4b078c86b41f810/1605972495995-YBX9K918HSOITB8CR5KZ/LC_17_190_137a-cs_1.jpg)

![Graffito of Esmet-Akhom from Hadrian's Gate at Philae (394 CE) [Wikimedia].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5449167fe4b078c86b41f810/1606334179764-SA0HL27JFAYN3QKWHKPM/1024px-Agilkia_Esmet-Achom_01.jpg)