Alan Taylor Farnes, “Scribal Habits in Selected New Testament Manuscripts, Including those with Surviving Exemplars,” (PhD dissertation; University of Birmingham, 2017).

In 2007, James R. Royse published his exceptional study on the scribal habits of six early New Testament papyri. Through demonstrating that scribes often omitted more than they added, Royse inverted text critics’ understanding of the text critical canon lectio brevior potior or, “the shorter reading is preferred.”[1] In its place he coined a new phrase: lectio longior potior or, “the longer reading is preferred.”

In the spirit of Royse’s method, my dissertation contributes to the conversation concerning variant length by approaching the problem from a different angle. Rather than analyzing early papyri, I chose to identify and analyze manuscripts with a known exemplar. This allows us to, as Royse says, “virtually look over the scribe’s shoulder and compare the text he is copying with his result.”[2] Some scholars have already followed Royse’s lead. For example, David Parker employs such a method, comparing a manuscript of the Latin Vulgate with a known exemplar and concluding the error rate of the manuscript included some ten changes per thousand words.[3] My dissertation, however, is the first attempt to understand scribal habits of Greek New Testament transmission by systematically analyzing such manuscripts. I conclude that the selected medieval and early modern scribes endeavored to copy the text as accurately as possible, neither interpolating additional statements nor corrupting the text for theological reasons. Furthermore, scribes who lacked proficiency in the language they were copying often produced an accurate copy of a clear text, but made confused errors when using a poorly written prototype.

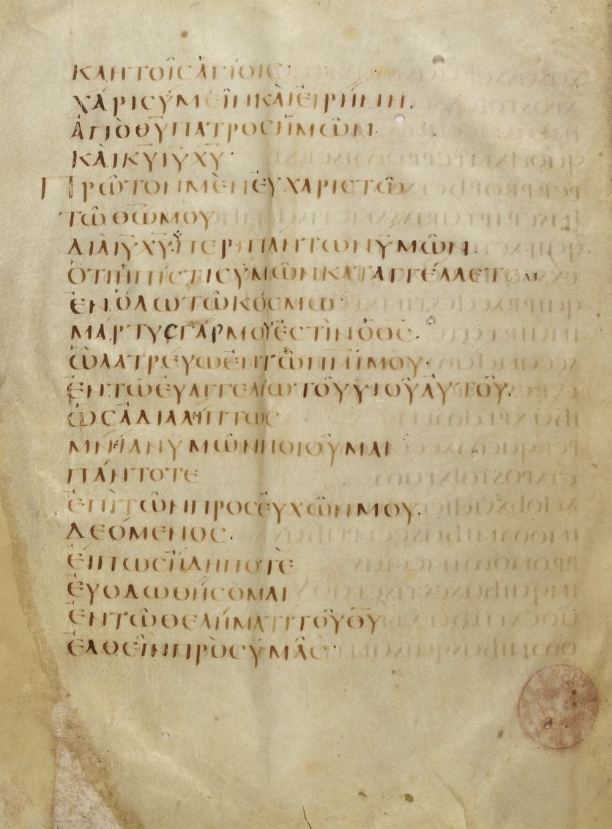

I identified twenty-two New Testament manuscripts with known extant exemplars, called Abschriften from the German word “copies.” Of these twenty-two I chose four manuscripts and their Abschriften to transcribe, collate, and analyze: the fifth-century copy of Paul’s letters Codex Claromontanus (06) and its two copies Codex Sangermanensis (0319) and Codex Waldeccensis (0320), the fifteenth-century copies of the entire bible minuscules 205 and 2886, and two catena manuscripts of the Gospel of John 0141 (tenth century) and its copy 821 (sixteenth century). How well did later scribes replicate the base text?

Chapter one reviews previous scholarship on scribal habits within New Testament textual criticism, with a keen eye to method. For example, Royse’s study used the “singular readings” method, according to which he transcribed, collated, and analyzed readings found in only one manuscript. A scholar using this method may attribute any variant to the scribe’s own creative work or error. I, however, disagree with the premise that a singular reading must be the invention of the scribe, due to the possibility that a singular reading may have existed in a manuscript’s lost exemplar. Additionally, Royse’s method must reconstruct a manuscript’s exemplar based on the manuscript in question and a knowledge of the textual tradition. If Royse’s method was consistently inaccurate, we could use Royse’s “singular readings” method and then apply the inaccuracy ratio to determine a more likely error rate. Unfortunately, analyzing Abschriften according to my own method along with the “singular readings” approach, Royse’s accuracy rate ranges from as close as 93% accuracy down to 40% accuracy. Royse’s method is therefore unreliable for texts with exemplars, even if it may remain the best method to use for the vast majority of manuscripts. We ought to remember, I maintain, that singular readings may be either the invention of the scribe or found in the scribe’s exemplar.

Chapter two discusses how manuscripts with known exemplars (Abschriften) have been used in textual criticism of the New Testament, the Greek translations of scripture often called the “Septuagint,” the Vulgate, and the Latin text of Livy. This chapter also outlines the methodology of the dissertation and, specifically, how to determine with accuracy the copying relationships between manuscripts. I rely on six steps for establishing such a relationship: (1) Does the proposed copy share a high percentage of textual agreement with another manuscript? (2) Do these manuscripts share a good number of peculiar dual agreements, or readings which are found only in these two manuscripts? (3) Can one of the manuscripts be demonstrated to be older than the other or were the two manuscripts created contemporaneously to each other? (4) Is there any evidence from the appearance of the text itself that one is a copy of the other? If the posited exemplar is damaged or faded in a certain location, perhaps the proposed copy will commit an error?[4](5) Does the proposed copy stumble over corrections in the exemplar or show their hand in any way? (6) Do the two manuscripts share similar codicological formatting, i.e. line breaks, page breaks, columns, pages, etc.?[5]

At the core of the dissertation, three chapters analyze the scribal habits of the copyists of various manuscripts. Chapter Three examines the scribal habits exhibited in P127—a fifth-century papyrus published in 2009 that contains an extensive portion of Acts.[6]P127is not an Abschrift but provides an opportunity to practice and test Royse’s method. Chapter Four examines the fifth-century Codex Claromontanus a bilingual Greek-Latin manuscript of the Pauline epistles and the earliest manuscript with extant copies.

I arrived at two surprising conclusions. First, both direct copies, the ninth-century Codex Sangermanensis (0319) and the tenth-century Codex Waldeccensis (0320), have exactly the same word count and, even more remarkably, without any words added or omitted. The scribes responsible still made substitutions, spelling mistakes, and nonsense errors but successfully retained their exemplar word-for-word.

Second, the accuracy of the scribe was linked to their linguistic proficiency. These manuscripts are diglots, containing both Greek and Latin. While scribes copied the text with a high degree of accuracy, their infrequent mistakes often resulted in a nonsensical error such as an imaginary Greek word. Their scribal habits when working with Latin, in contrast, aligned with the results one would expect in light of Royse’s new text critical dictum. In Latin, the same scribes who copied the Greek text lost words, and made the types of errors common with scribes proficient in the language. For example, most of the variants between Claromontanus’ Latin text and its copies were a result of emendations to align the text with the Vulgate, which resulted in numerous substitutions but very few nonsense errors. In short, the scribes were more proficient in Latin. The full significance of this study awaits further research on the habits of scribes copying a language with which they are unfamiliar.

This chapter also investigated how the hidden hand of the patron can show itself. For Codex Sangermanensis (0319), the two scribes were very different individuals with different scribal habits. Scribe 0319A seems to have had at least enough Greek knowledge to pronounce (or mispronounce) words which led to many orthographic variants. Scribe 0319B, however, made only one orthographic variant, and was thus ironically a better copyist with respect to significant variants and total variants. Neither 0319A or 0319B added or omitted any text. What is even more striking, however, are their shared scribal attributes. Both 0319A and 0319B usually followed the same corrector (06***). Additionally, they both ignored marginal corrections, preferring instead only corrections in the main body of the text. These shared corrective tendencies, in spite of the scribes’ distinct habits, suggest a patron was behind the production of this manuscript, and instructed both scribes regarding copying and emending the text. If patrons played a more substantive role in textual transmission than previously thought, we should therefore at each point of variation endeavor to determine responsibility: the patron, a reader,[7] or, lastly, the scribe.

Chapter five discusses whether two fifteenth-century manuscripts, 205 and 2886, were copies of one another. Since the nineteenth century, scholars have considered 205 to be the exemplar and 2886 to be the direct copy. Even the editors of Nestle-Aland accepted that 2886 was a copy of 205 and so designated 2886 as 205abs (short for Abschrift). Alison Welsby, however, argued that the direction of borrowing should be reversed.[8] Following the six steps used in Chapter 2 to establish if a manuscript is a copy of another manuscript, however, I conclude, agreeing with Josef Schmid,[9] that 205 and 2886 are likely both copies of a now lost exemplar.

Chapter six analyzes two catena manuscripts of John: the tenth-century 0141—the exemplar—and its sixteenth-century copy, 821 copied by a man named Camillus Venetus and commissioned by Cardinal Francisco de Mendoza.[10]A catena manuscript is a continuous text copy of the New Testament, interspersed with commentary from early church Fathers. Venetus’ habits are what we would expect to see from most Greek scribes. Over the course of more than 4,000 words he added one word and omitted seven. Therefore, while being incredibly accurate, Venetus lost more words than he added and had an error rate of 2.22 total variants per thousand words. This is the lowest error rate of any scribe in this study and in Royse’s study. In fact, the error rate of the scribes in this study decreased as the centuries rolled by. This may suggest that over time the scribes became better copyists and the text became more stable. This could be likely due to an increased intimacy with the text over hundreds of years and due to the ossification of the text in the sixteenth century—by the sixteenth century any changes made by a scribe would have been easily noticed but more research is needed to place these claims on firmer ground.

I conclude that my sample of scribes did their best at a difficult job of copying manuscripts. The most blatant intentional changes were the Latin scribes copying 0319 and 0320 who consistently altered the wording from Claromontanus’ Old Latin to update their text to the Vulgate. Some of the scribes in this study lost words, but none gained them. With respect to the scribes in this study, therefore, we can reject the older canon lectio brevior potior. We are unable, however, to confirm Royse’s new canon of lectio longior potior. Instead,I argue that length should not be used in any way to determine which reading is more original.

[1] James R. Royse, Scribal Habits in Early Greek New Testament Papyri (NTTSD 36; Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2008), 732.

[2] Royse, Scribal Habits, 34.

[3] David C. Parker, “A Copy of the Codex Mediolanensis,” JTS 41.2 (1990): 537–41.

[4] See, for example, Ronald H. van der Bergh, “The Influence of the Greek OT Traditions on the Explicit Quotations in Codex E08,” in Textual History and the Reception of Scripture in Early Christianity (SCS 60; Johannes de Vries and Martin Karrer eds.; Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2013), 135 and David C. Parker, “A Copy of the Codex Mediolanensis,” JTS 41.2 (1990): 537–41 who have used this method to determine direct copies.

[5] See Tommy Wasserman, “The Patmos Family of New Testament MSS and Its Allies in the Pericope of the Adulteress and Beyond,” TC: A Journal of Biblical Textual Criticism 7 (2002): §6.3.40 and Theodora Panella, “Resurrection Appearances in the Pauline Catenae,” in Commentaries, Catenae and Biblical Tradition: Papers from the Ninth Birmingham Colloquium on the Textual Criticism of the New Testament, in association with the COMPAUL project (ed. H. A. G. Houghton; Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2016), 121 who have used this method to determine direct copies.

[6] D. C. Parker and S. R. Pickering, “4968. Acta Apostolorum 10–12, 15–17,” in D. Leith et. al. eds., The Oxyrhynchus Papyri LXXIV (London: Egypt Exploration Society, 2009), 1–45.

[7] Many text critics believe that most intentional changes actually were not made by a scribe at all but rather by later readers. Michael Holmes has stated: “We must not forget that [NT manuscripts] were copied and read by individuals, with widely varying levels of skill, taste, ability, and scruples” (Michael W. Holmes, “Codex Bezae as a Recension of the Gospels,” in Codex Bezae: Studies from the Lunel Colloquium, June 1994 (D. C. Parker and C.-B. Amphoux eds.; NTTS 22; Leiden: Brill, 1996), 148, emphasis in original). He continues, “A well-educated, well-informed, conscientious but unscholarly anonymous reader is much more likely to have been responsible than any ‘important personality’” (Holmes, “Codex Bezae,” 149, emphasis in original). Elsewhere Holmes has written that the origin of many of the substantive deliberate variants “are due to the activity of educated, thoughtful, usually conscientious but unscholarly readers (as distinguished from pure copyists as such)” (Michael W. Holmes, “The Text of P46: Evidence of the Earliest ‘Commentary’ on Romans?” in New Testament Manuscripts: Their Texts and Their World (TENTS 2; Thomas J. Kraus and Tobias Nicklas eds.; Leiden: Brill, 2006), 201, emphasis in original). Larry Hurtado agrees and writes that he has been persuaded that “We should view most intentionalchanges to the text as more likely made by readers, not copyists” (Larry W. Hurtado, “God or Jesus? Textual Ambiguity and Textual Variants in Acts of the Apostles,” in Texts and Traditions: Essays in Honour of J. Keith Elliott (NTTSD 47; Jeffrey J. Kloha and Peter Doble eds.; Leiden: Brill, 2014), 239, emphasis in original).

[8] See Alison Welsby, A Textual Study of Family 1 in the Gospel of John (ANTF 45; Berlin: De Gruyter, 2014), 49–54, 80–84 and Alison Sarah Welsby, “A Textual Study of Family 1 in the Gospel of John,” PhD diss., University of Birmingham, 2011, 72–80, 120–126.

[9] See Josef Schmid, Studien zur Geschichte des griechischen Apokalypse-Textes, vol. I: Der Apokalypse-Kommentar des Andreas von Kaisareia. Einleitung (Munich: 1956), 287–93.

[10] 0141 seems to actually have two extant copies being copied also by the sixteenth-century 1370, but I was unable to procure digital images of this manuscript and I was unable to travel to Berlin to transcribe it in person. I hope to complete the study of this family in the near future.

Alan Taylor Farnes is currently an adjunct instructor of Ancient Scripture at Brigham Young University. You can find him on Twitter @alanfarnes. The complete text of this dissertation is freely available here.