Last November, I participated in a collaborative syllabus workshop called “Politics, Pedagogy, and the Profession,” offered at the annual 2017 Society of Biblical Literature and American Academy of Religion conference in Boston. This workshop was generously supported by a Wabash grant and hosted by Harvard’s Center for the Study of World Religions. The two-day seminar brought together graduate students, junior scholars, and seasoned professors to reflect on teaching strategies and pedagogical plans for both classroom and syllabus in light of our modern political situation. In this blog post, I outline four practical ideas discussed during this workshop pertaining to using maps in the classroom that can be effective in pedagogical practice.

Laminated Maps Offer Unlimited Opportunities

My first-year biblical studies course always includes a unit on parables from the canonical gospels. I emphasize that reading and interpreting these parables involves understanding them within their historical, geographical, political, and socio-cultural context. One class focuses on the parable of the “Good Samaritan” found in Luke 10:25-37. I begin by giving the students a laminated map of first-century Palestine, along with dry erase markers. Dividing them into small groups, I list places for them to find on the map, including Judea, Samaria, Jerusalem, Jericho, and Mount Gerazim. Then I ask them to trace a possible route between Jericho and Jerusalem, and to note their observations about terrain, elevation, and route length. After ten minutes of small group discussion, they report back to the larger group and I provide a brief explanation about the separation of the communities now referred to as Samaritans and Jews, as well as the Samaritan’s place of worship, Mt. Gerazim.[1]

Pedagogically, this exercise works in a couple of ways. First, it encourages students to work together in dialogue. While students explore independently alongside one another, they also discover, for example, that the Samaritans were also connected to the land of Palestine, and continued to worship there even while other groups were in exile. Second, it emphasizes the historical context of the parable and situates the text into its geographic setting. Students find out that the cities mentioned in this parable still exist, located in an area of fundamental importance for many modern political conversations concerning Israel/Palestine. As students think critically within this exercise, they might even begin to make connections to current political discussions involving this piece of land that has been the source of such strife for centuries.

This type of mapping exercise offers instructors and students further benefits. First, in terms of conserving resources, these maps are reusable. Second, this mapping strategy also does not require the use of technology in the classroom. This may be preferable to professors who are not comfortable with digital technology, or who have classrooms that lack advanced tech support. Third, I find it useful to have moments throughout the semester where students (and myself) put down our phones and laptops. These opportunities shift our classroom relationship to technology, emphasizing dialogue rather than the more individualistic pointing, clicking, and information processing.

Laminated maps can be adapted for biblical texts beyond the parable of the Good Samaritan, of course. For example, they have proven useful in my Introduction to New Testament course when discussing the gospels. In groups, I ask students to find cities such as Capernaum, Magdala, Bethsaida, and Jerusalem on the map and search for biblical passages where these cities are listed. Students can also draw borders using different colored dry erase markers, illustrating how borders changed throughout the region’s history. Using a laminated map of the ancient Mediterranean World, students work together to outline the territory occupied in the conquests of Alexander the Great and then dissolve those same boundaries as they chart the growth of the Roman Empire. This type of exercise actively engages students by pulling them into the narrative of the gospel. In this way, a map serves as a visual illustration of the ancient text we are reading; students journey alongside the author of the text through their participation in the mapping exercise.

Virtual Exploration Using Google Maps and Earth

While the above is a relatively low-tech way of using maps in the classroom, the following three examples are for the more technologically advanced.[2] The first of these tools, Google Maps, can be extremely useful in the classroom as both free and user friendly. When one utilizes the 3D function as well as street view, a user can zoom in to view maps in high detail. For instance, an instructor can bring up Google Maps on the classroom computer and locate various cities and sites mentioned in the assigned reading. I do this as a group activity using university-owned iPads, but students are also able to use their laptops or smart phones for such an activity.

During the November pedagogy workshop in Boston, several instructors mentioned employing this technology to introduce students to Pergamon and Corinth, archaeological sites located in Turkey and Greece. I have also taken a virtual journey with students to the archaeological site of Pompeii, where several of the historical sites can be examined more closely using Google Maps street view. Using Google Maps and Google Earth also helps increase students’ geographical awareness and connects antiquity to current global political issues. Often, students are unaware that the very places mentioned in ancient texts are present on current maps as well.

Anyone attempting this exercise for the first time should be aware that there are some advantages to using Google Earth instead of Google Maps. The satellite images in Google Earth are clearer and the user can zoom in closely. Google Maps is easier to access, however, especially if your classroom does not have up-to-date technology. To compensate, when I use Google Earth in my classes I often bring my own laptop and load the site before class. This saves time during set up and ensures the in-class example goes smoothly.

On the other hand, since many of my students have smart phones, they can use Google Maps individually or in groups. This type of independent pedagogical exercise can encourage students to follow their own interests. Often they discover things that I would not have showed the class in my lecture or example, and so after time exploring Google Maps together, I try to allocate a few minutes for groups to report to the class what they found in smaller groups. This way, students also learn from their peers.

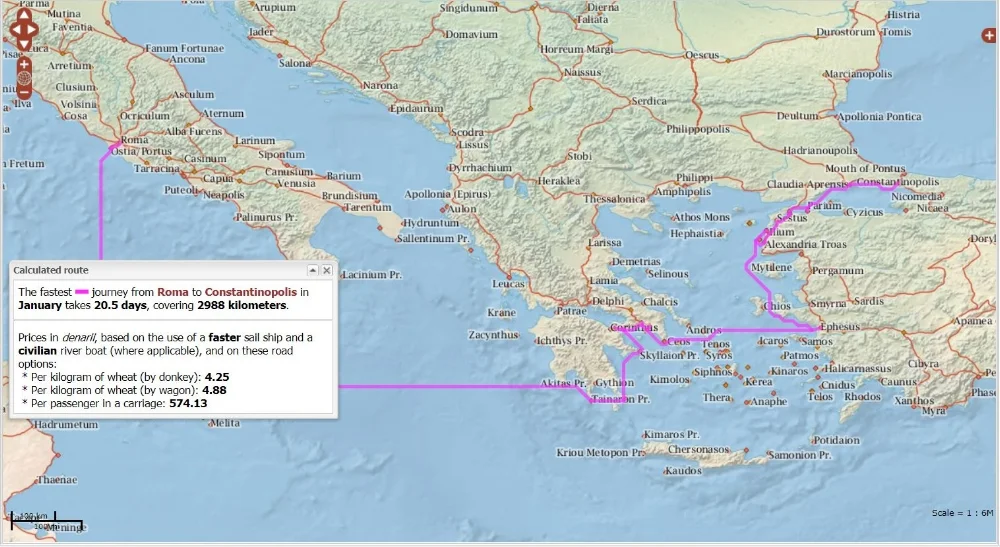

Interactive Mapping in Antiquity with ORBIS (http://orbis.stanford.edu/)

My third tool, the Stanford Geospatial Network Model of the Roman World (ORBIS), lets you take your class on a realistic journey around the Roman World using. This fantastic interactive mapping tool allows the user to choose and analyze travel routes from the ancient world. As the website notes, Google Maps does not take into account the travel complexities present in antiquity, nor the various costs associated with long distance travel. ORBIS therefore includes a map that covers three continents that were each a part of the Roman Empire and were accessible through various means of transportation in antiquity.

Presenting ancient travel in this context-sensitive way, ORBIS allows the user to choose ancient cities for the “start” and “destination.” A specific month may be selected as well, since seasons often affected the length and path of travel. The user can then prioritize their hypothetical travel plans by speed, cost, or distance. Using roads, rivers, and seas, one can even designate their traveler as a member of the military or a civilian, as well as a variety of options: foot/army/pack animal; rapid military march; ox cart; porter/fully loaded mule; horseback rider (routine travel); private travel (routine, vehicular); private travel (accelerated, vehicular/horseback); fast carriage; and horse relay. After the user selects their options, ORBIS generates a route that includes how many days and kilometers the journey will take, prices listed by denarii, and the price per passenger.

The possibilities for a website such as this in the classroom are endless! For example, when teaching a class on the New Testament class or Paul, students can attempt to map one of Paul’s journeys as outlined in the book of Acts. In a class or unit focused on pilgrimage, students can determine the costs and difficulties of making such a journey in Roman times. In a course on Early Church History, students can each choose a city and determine how someone might have traveled to attend the Council of Nicaea, as in the screenshot above. This tool, also, can connect to our present-day contexts. One might ask the students to consider the travel constraints that exist for a family or individual of limited means who desires to go on a religious pilgrimage.

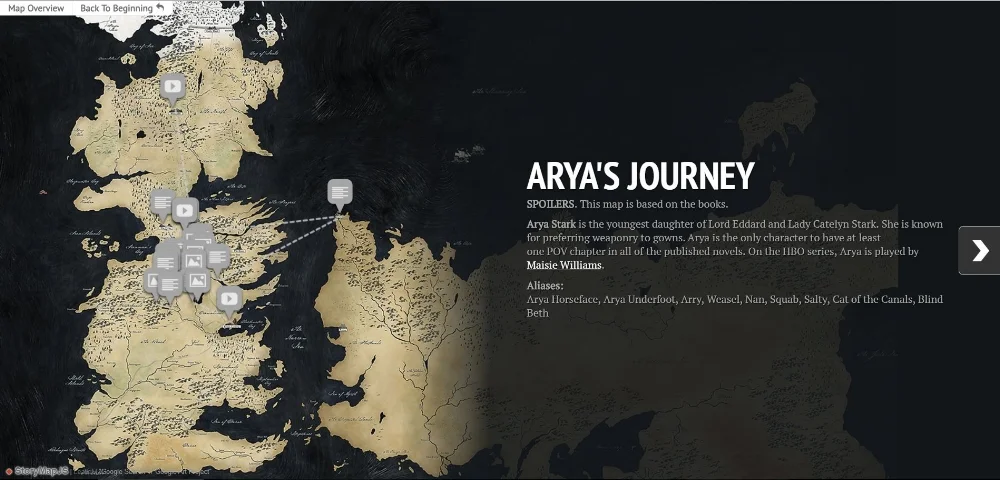

Larger Creative Mapping Assignments via StoryMapJS (https://storymap.knightlab.com/)

The options I've discussed so far are great ways to incorporate maps into day-to-day lesson plans. My fourth and final example of map-use in the classroom uses maps as the focus for a larger project, such as a mid-term or final project. StoryMapJS, a free tool from Northwestern University's Knightlab, enables students to incorporate more traditional written analysis (a historical narrative, for instance) into an online exhibit alongside either a digital map or other digital images. There are several examples on the Knightlab site, including this creative one designed around HBO's Game of Thrones series. The final product guides the viewer around the map or image, focusing on different locations chosen by the creator, and displays textual analysis alongside the map/image.

One aspect of Knightlab that can be especially helpful when teaching ancient texts is the ability to upload any chosen map into the site. With the Juxtapose tool (https://juxtapose.knightlab.com/ - overview), users can place maps side-by-side and create a storyline to accompany the maps and explain the differences, as in this example which includes maps of Berlin from 1945 and today (http://interaktiv.morgenpost.de/berlin-1945-2015/). While many of the examples on the site are for contemporary or recent events, similar projects can be created using maps and images from antiquity. For example, in a course on Slavery and the Greco-Roman World a student could choose a city with an active slave market (such as Ephesus, Turkey) and upload an ancient map to the website. Then, the student could write and create a StoryMap to outline a possible journey for a slave bought or sold in Ephesus and taken to a rural domestic residence. This type of assignment can activate a student’s imagination and bring antiquity to life through an interactive presentation that can then be shared with the class.

Knightlab provides an easy-to-follow guide for StoryMapJS, but creating a larger scale digital assignment for the first time will likely require more of an instructor’s time, and will feature a steeper learning curve for both instructor and student. For this reason, it would be wise to set aside one or two class sessions to ensure that everyone feels comfortable with the technical requirements of the project. Students and instructors alike, however, often find a digital assignment like this to be a welcome change of pace. Moreover, the fact that students will end the class with an easy-to-share online project gives them something tangible to share with their peers and outside of class, or even to include in an e-portfolio or website.

Maps as Pedagogy

As these four examples show, using maps in the classroom is a constructive addition to both undergraduate and graduate level classes. Maps provide opportunities for active learning and also situate ancient texts in a global context. Students examine ancient maps and discover that many of these places still exist and, in fact, are very important to our political and geographic context today. Borders change, today and throughout history. Incorporating maps into the classroom encourages the students to view this for themselves and to begin to understand the myriad of ways that politics shapes geographical borders. Moreover, mapwork fosters co-learning in the classroom environment. Students learn from one another and frequently, professors learn from students as well. Finally, these exercises can also be incorporated into an online or hybrid class, enabling students to participate with these websites and contribute to the course through their own exploration.

[1] For more information on this topic, see: Knoppers, Gary N. Jews and Samaritans: The Origins and History of Their Early Relations. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. For concise articles available online, see Pummer, Reinhard. “The Samaritans in Recent Research” http://bibleinterp.com/articles/2015/12/pum398030.shtml Zangenberg, Jügen “The Samaritans” (https://www.bibleodyssey.org/people/related-articles/samaritans) and Rindge, Matthew S. “The Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25-37)” https://www.bibleodyssey.org/passages/main-articles/good-samaritan).

[2] For even more examples of ways to incorporate digital mapping into the classroom, see this post by classicist Sarah Bond: https://sarahemilybond.com/resources-for-teaching-gis-mapping-and-ancient-geography/.

Christy Cobb is Assistant Professor of Religion at Wingate University.